Europe’s turbocharged electricity transition is in full swing. Wind and solar capacity additions continue to break records. The outlook for solar remains positive and Wind Europe recently forecasted that rising annual deployment will take the European Union close to its REPowerEU ambitions for wind.

This is good news for Europe, particularly amid geopolitical tensions and high inflation. A cleaner electricity mix reduces power prices, bringing benefits for consumers and industry alike. Indeed, there is a clear link between a successful energy transition and Europe’s industrial competitiveness and financial stability. Clean electricity is also crucial for reducing Europe’s dependence on volatile fossil-fuel imports, ensuring greater energy security across the bloc.

However, as clean technology investment hits records, it is coming up against the hitherto overlooked barrier of grid capacity. Signs of stress in the system are becoming increasingly visible, drawing attention to the central role of grids in decarbonising Europe’s economy and pushing this far up the political agenda. Long grid-connection queues have already built up, with more than 600 gigawatts of wind and solar stuck in the pipeline in just four European countries, while renewables are increasingly subject to output curtailments.

The issue is thus not renewables but the grids to which they need to connect. There is a direct link between renewable curtailment caused by grid congestion and lack of progress on grid development.

Not fit for purpose

The way grids are being planned is no longer fit for purpose. A recent report by the energy think-tank Ember suggests that frameworks for network planning are not aligned with the reality of an energy transition at full tilt.

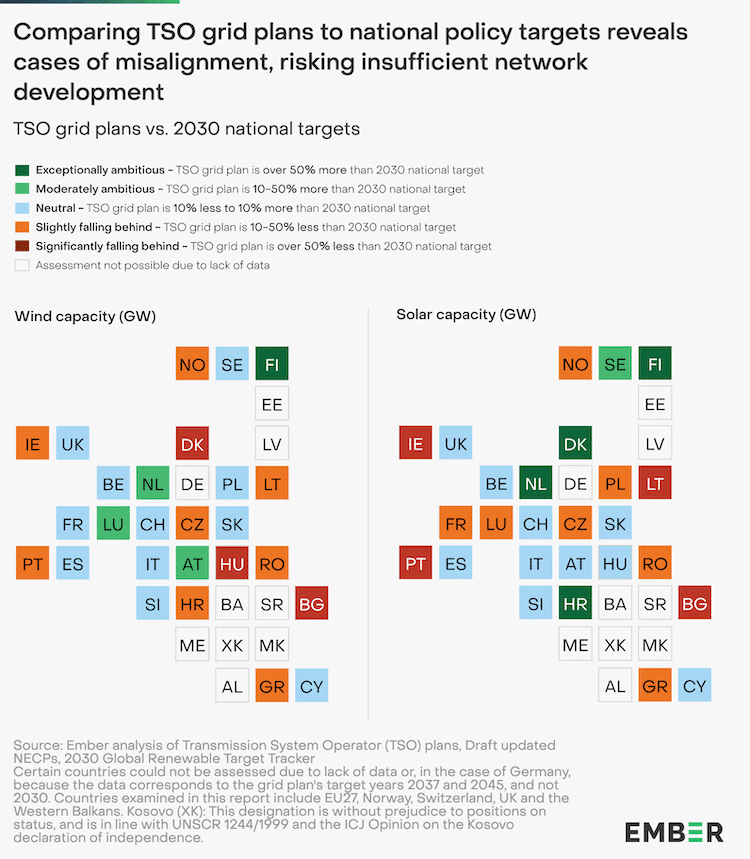

Ember’s analysis compared grid plans from 26 transmission system operators (TSOs) in Europe with the energy policy targets for wind and solar in their respective countries. Of these, 11 grid plans were found to be based on energy scenarios which significantly undershot existing policy targets. As policy ambition increases and market trends soar, networks risk being insufficiently prepared to integrate the anticipated wind and solar roll-out.

Grids must play an enabling role in the energy transition, delivering wind and solar from its source to the end user. Yet outdated plans could leave grid investment and development lagging behind what is needed, creating a physical barrier to the transition instead.

Time lag

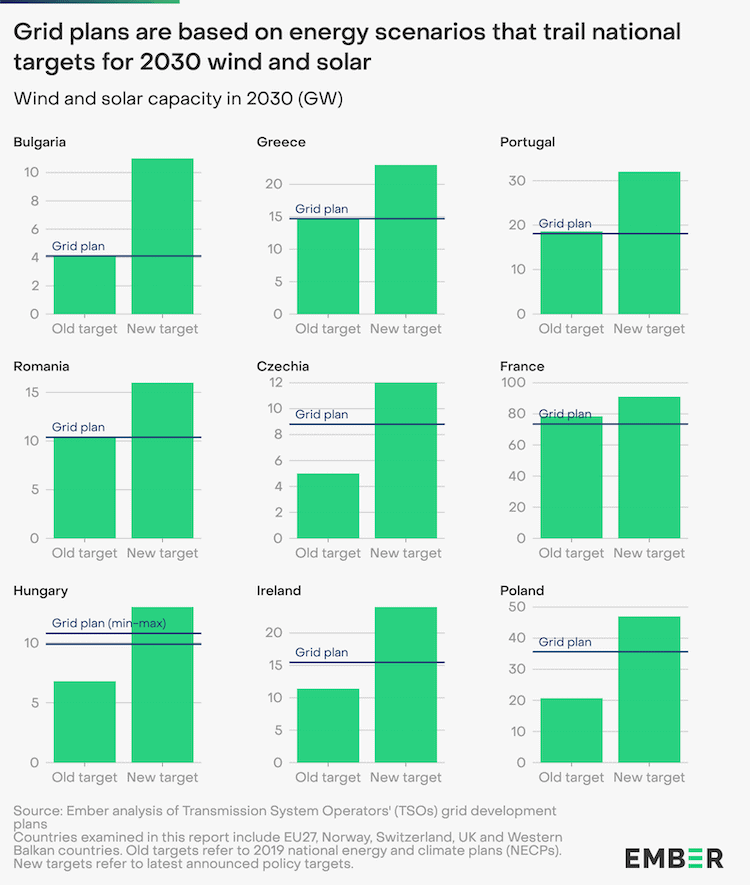

This misalignment between grid plans and policy targets likely stems from a time lag between the setting of national policy and development of the plans. Regulation in many countries requires TSOs to abide by energy targets enshrined in national legislation. However, the process of transposing political targets into legislation often takes about two years—and a grid plan based on such targets takes an additional two years to be developed.

This means that a grid plan published in 2023 would be based on national policy targets transposed into legislation in 2021, which were probably discussed at the political level in 2019 or 2020. Network planning is therefore systematically lagging behind the increases in EU and national ambition. Additionally, targets themselves often lag behind external conditions, such as market outlooks. As a result, grid plans struggle to keep up with the fast evolution of the energy landscape.

Such falling behind is highlighted when TSO grid plans are compared with market forecasts of solar deployment. Solar is consistently underestimated in grid plans, with 19 countries out of the 23 which could be assessed using significantly lower 2030 capacity figures to plan their power grids. Across these plans, solar is underestimated by a total of 205GW—a staggering figure close to the entirety of solar installed in the EU today (263GW). This disconnect from on-the-ground trends implies that, unless remedial actions are taken, grid congestion may worsen in the short term and larger volumes of solar capacity may become stuck in grid-connection queues.

That gulf extends across fast-developing clean technologies, including wind (although it is far less misaligned) and batteries. While grid plans are not specifically designed to take market trends into account, they should be sufficiently forward-looking to adapt to evolving investment landscapes. This is especially important as clean energy technologies can be deployed much more quickly than transmission lines can be built or upgraded.

More forward-looking

Europe must follow two courses of action to ensure that grids do not remain barriers to the energy transition. First, implementing a variety of non-wire solutions can, swiftly and cheaply, alleviate stress in the system, increasing capacity on the grid. One option is to improve load flexibility—lowering peak withdrawals and injections through storage, demand-side responses and financial instruments. The Dutch TSO TenneT, for instance, has proposed initiatives for large companies and major consumers to use less electricity at peak times to alleviate pressure on its grid, linked to financial incentives.

Secondly, national regulatory frameworks must be revised to enable grid operators to be more forward-looking. Power networks should be ready to facilitate renewable and clean technology deployment, but this will not be achieved if grid plans remain exclusively rooted in targets established in national legislation at the start of the planning cycle. Regulation should encourage grid operators to use energy scenarios which better reflect evolving policy discussions and market outlooks to plan their networks.

Some grid operators, such as the German and Finnish TSOs, have already adopted such an approach, implementing ‘target grid’ strategies which look ahead to 2040 and beyond. This is also key to enabling anticipatory grid investments, a hot topic at EU level: it is clearly impossible to identify such investments if grid planning is restricted to the boundaries of current or, worse, outdated policy.

The political momentum around grids must be harnessed to implement solutions to address the critical and tangible problem of grid capacity, which risks holding back the energy transition.

Elisabeth Cremona is an energy and climate data analyst at Ember, an independent energy think-tank providing data, analysis and policy solutions on accelerating the global electricity transition.