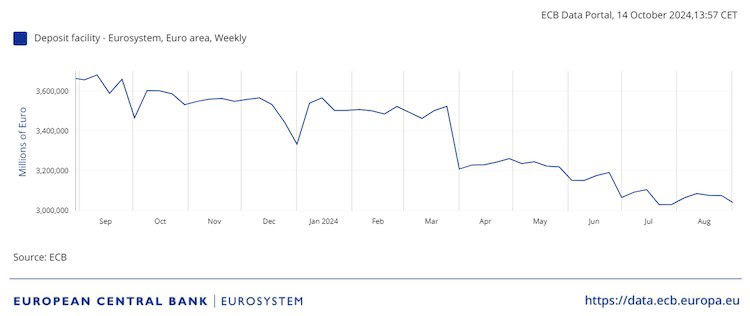

The major central banks pay interest on commercial banks’ reserve holdings. To combat inflation, these central banks began to raise interest rates in late 2021. Consider the example of the Eurosystem: bank reserves held by credit institutions at the national central banks and the ECB exceeded €3.6 trillion in September 2023. Since April 2024, this figure has declined significantly, but in August 2024, it remained at a substantial level of €3.15 trillion (see below). In September 2023, the remuneration rate on these reserves held by commercial banks was raised to 4% and subsequently reduced to 3.75% in June 2024. This means that the Eurosystem has paid out at least €126 billion in interest to credit institutions from September 2023 to August 2024. Other central banks, particularly the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England, follow the same practice of increasing the interest rate by raising the remuneration rate on bank reserves.

To give you an idea of the size of these transfers in the Eurozone, consider the following: with a transfer of €126 billion by the Eurosystem to Eurozone banks between September 2023 and August 2024, we are approaching the yearly total spending of the EU, which amounts to €168 billion. This situation is even more remarkable when considering that the transfers by a European institution to banks are decided without any political discussion and are granted without attaching any conditions. This contrasts with EU spending, which results from an elaborate political decision-making process and is usually accompanied by stringent conditions.

Today, many economists and central bankers take it for granted that bank reserves are remunerated. Yet, this remuneration is a recent phenomenon. Before the start of the Eurozone in 1999, most European central banks did not remunerate banks’ reserve balances. During the 1970s and 1980s, for example, the Bundesbank used very high unremunerated minimum reserve requirements to siphon off large inflows of money into the country.

The ECB started the practice of remunerating bank reserves in 1999. The Federal Reserve only introduced the remuneration of banks’ reserve balances in 2008. Thus, before 2000, the general practice was not to remunerate banks’ reserve balances. This made good sense: commercial banks do not remunerate demand deposits held by their customers. These demand deposits have the same function as bank reserves at the central bank: they provide liquidity for the non-bank sector. These are not remunerated. It is difficult to justify why bankers should be paid when they hold liquidity while everybody else must accept not being remunerated. Furthermore, the substantial remuneration of bank reserves creates several problems.

First, when the central bank makes interest payments to commercial banks, it transfers part of its profits to the banking sector. Central banks make a profit (seigniorage) because they have obtained a monopoly from the state to create money. The practice of paying interest to commercial banks amounts to transferring this monopoly profit to private institutions. This monopoly profit should be returned to the government that granted the monopoly rights. It should not be appropriated by the private sector, which has done nothing to earn this profit. In fact, it is worse. The transfers are now so high that not only are all the profits of central banks transferred to banks, but central banks also incur significant losses that will have to be borne by taxpayers. The current situation of paying interest on banks’ reserve balances amounts to a subsidy to banks, paid out by the central banks at the expense of taxpayers.

Second, the problematic nature of remunerating bank reserves also emerges from the following. Banks are “borrowing short and lending long.” In other words, banks hold long assets (with fixed interest rates) and short liabilities. As a result, an increase in interest rates typically leads to losses and reduces banks’ profits because the interest cost of their liabilities rises quickly while the interest revenues take longer to increase. Banks are expected to hedge this interest rate risk. However, this is costly, so they are often reluctant to purchase such insurance. By remunerating bank reserves, the central banks provided free interest hedging. Banks received immediate compensation from the central banks when interest rates rose.

Paradoxically, when central banks were combating inflation by raising interest rates, banks avoided the burdensome loss profile as they earned substantial profits during the period of interest rate increases in 2022-23. This was possible because central banks took over this burden from the commercial banks. It is difficult to understand the economic rationale of a system where public authorities provide free insurance for the banks’ interest rate risks at taxpayers’ expense. It is also worth noting that when central banks raised interest rates in the 1970s and 1980s to tackle inflation, they did not incur losses. Instead, they increased their profits. One of the main reasons for this was that they did not remunerate bank reserves.

One might argue that while the large transfers to banks were unfair, these transfers were inevitable in effectively combating inflation. In fact, the opposite is true. The current system of remunerated bank reserves enhances banks’ profits and, in doing so, strengthens their equity position when the central bank raises interest rates to fight inflation. As a result, this system incentivises banks to increase the supply of bank loans. Thus, the current system has reduced the effectiveness of the transmission of monetary policies, which, during 2021-24, focused on reducing inflation.

The remuneration of bank reserves is not inevitable. There is an alternative. We propose implementing a tiered system. This consists of defining a tier1 of non-remunerated reserves and a tier2 that is remunerated. As an example, suppose a bank holds 100 units of bank reserves. The central bank could define tier1 to consist of 50 units and tier2 to consist of 50 units. The tier2 part can also be termed excess reserves and is remunerated at the same deposit rate that the ECB has applied.

Such a tiered system allows for a significant reduction in the transfer of central banks’ profits to private agents, enabling central banks to maintain their current operating procedures. Thus, when the central bank wants to raise the interest rate to combat inflation, it increases the deposit rate applied to tier2 reserves. This rise in the deposit rate has the same effect on the market interest rate as the current system, but results in fewer transfers to banks making the system fairer whilst enhancing the effectiveness of monetary policies.