The centrality of market mechanisms to the European Commission’s climate package poses big questions as to its effectiveness and distributional impact.

The climate policy package ‘Fit for 55’ launched by the European Commission on July 14th is ambitious and seems to put the European Union on track towards its 2030 climate-policy targets and pave the way for the 2050 net-zero-emissions goal. So far, so good.

But is Europe also socially fit for this package? Is it in line with the principle of ‘just transition’, widely shared across the union and the EU institutions? While previous efforts in this regard focused more on the employment, regional and industrial-policy aspects—the main areas covered by the Just Transition Fund established under the European Green Deal—this time the distributional features of just transition are on the table.

Key elements of the package are a new emissions-trading system (ETS) for fuel distribution for road transport and buildings—the first time carbon markets would have a direct effect on the population—and a Climate Social Fund.

Regressive distributional effects

It has been argued for a long time (by Cambridge Econometrics, the European Climate Foundation, L’Institut du développement durable et des relations internationales and the European Trade Union Confederation) that an ambitious and effective climate policy needs a balanced framework. Objectives can only be reached by the simultaneous and well-proportioned deployment of regulation, standards and market mechanisms. While these last are essential to set price signals to market actors, to change investment and behavioural patterns, they can only have the desired effects in well-functioning markets.

This is however far from the case with carbon markets—and road transport and buildings in particular. Decarbonisation in these two sectors was lagging behind the rest of the economy and they need to embark on a more radical path. But both have market ‘rigidities’: their emissions do not respond to price signals. Since the required low-carbon technologies will thus take time to become available, there will be a period when consumers will face a higher carbon price while locked into fossil-fuel-based systems with limited alternatives.

Moreover, such signals have massive, regressive, distributional effects—disproportionally affecting low-income households, for whom fuel and transport consume a higher share of their income. They also have less capacity to change, as while low-carbon products (electric vehicles, rooftop solar panels and so on) may have low operating costs they tend to have high, upfront capital costs—presenting a hurdle for households with little access to cheap capital.

Consumers, in particular those on lower incomes, often have insufficient information about available low-carbon alternatives. Those in a precarious situation also have a short-term planning horizon and so discount potential, long-term cost savings. And here a malfunctioning carbon market can be compounded by ill-conceived regulation, such as weight-based emission standards favouring SUVs while penalising small petrol vehicles.

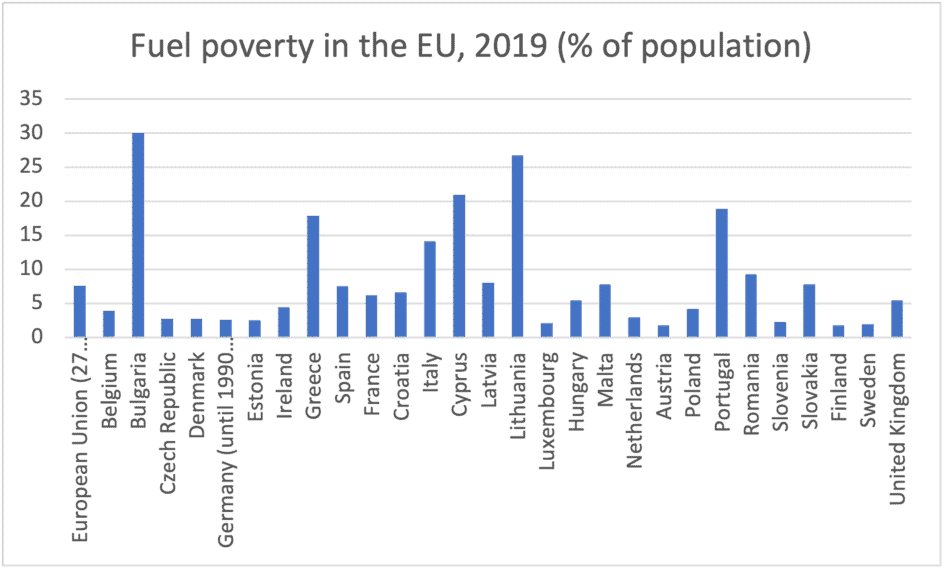

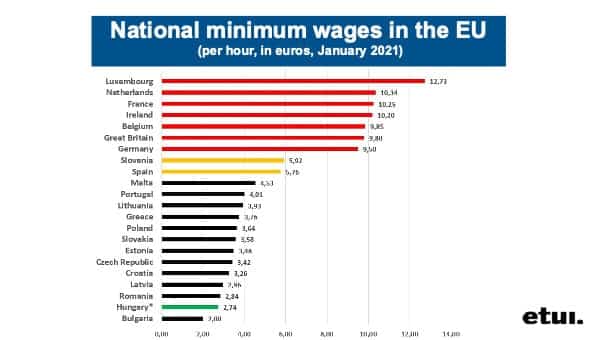

Looked at through a distributional lens, the apparent ‘level playing-field’ of an EU-wide carbon price, in critical sectors with a direct impact on consumers, will have massive effects on inequality—between as well as within member states. The EU is far from a social level playing field and a single price will have a different effect on the population in Luxembourg than in Bulgaria, which has the highest fuel poverty and lowest minimum wages in the union (see figures).

Unsatisfactory response

The proposed Climate Social Fund is a necessary, but unsatisfactory, offsetting response. The huge challenge of designing an effective and fair compensation mechanism—covering various inequalities, degrees of market accessibility and levels of market information—has been massively underestimated. Setting up a carbon market is easy; creating a proper compensation mechanism in a heterogenous, 27-member economic area is much more difficult.

The size of the fund is to be €72.2 billion between 2025 and 2032, using 25 per cent of the ETS revenues from transport and buildings, with potential match funding from the member states. This is very low compared with the challenges posed by extending the ETS in this way. The purpose of higher carbon pricing is in any event not to raise revenue but to direct market behaviour towards low-carbon technologies—there is thus a strong argument for redistributing fully the additional revenues.

The structure of the fund also raises several questions. Only a part of it is to be dedicated to social compensation; the rest includes incentives for electric vehicles and investments in charging infrastructure and decarbonisation of buildings. Low-income households would not benefit from these measures—indeed, using the fund to support electric vehicles would disproportionally favour rich households. For low-income households the priority would be changing their old polluting cars into more fuel-efficient ones, calling for a thorough re-regulation of Europe’s second-hand-car markets.

In considering the distribution of the fund among member states, the commission has made the effort to create a formula to account for population size (including the rural share), per capita gross national income, the share of vulnerable households and household emissions from fuel combustion. But this will still not manage adequately to take within- and between-country inequalities into account. A relatively poor member state with lower within-country inequality could end up benefiting less than a rich member state with high inequality.

Member states will have to submit Social Climate Plans together with their National Energy and Climate Plans by 2024, identifying vulnerable groups and measures. How will this work, given their large differences in commitment and institutional capacity? The huge disparities among member states in how their National Energy and Climate Plans have addressed just transition in the past might provide a foretaste of what to expect.

Béla Galgóczi is Senior Researcher at the European Trade Union Institute and editor of Response measures to the energy crisis: policy targeting and climate trade-offs (ETUI, 2023).