The European Union is often criticised as ‘technocratic’. Actually the problem is how business lobbies are seen as ‘neutral’ voices on deeply political issues.

The single market. EU digital strategy. Industrial policy. These are just some of the big issues in the ‘Brussels bubble’ on which corporate interests are lobbying—including at meetings of a little-known group, part of the Council of the EU. Worryingly, alternative voices to the corporate consensus are rarely being heard.

The council is already a ‘black box’ when it comes to the transparency of its law-making. But inside it, just like a matryoshka doll, there are further sets of black boxes: working parties, preparatory bodies and sub-groups, which play a key role in developing positions on proposed legislation for member-state ministers to agree. Officials from the 27 member states attend thousands of meetings of these groups every year.

New research into just one, the Working Party on Competitiveness and Growth, has revealed how it offers privileged access to corporate interests, to present and discuss their EU policy demands.

Privileged access

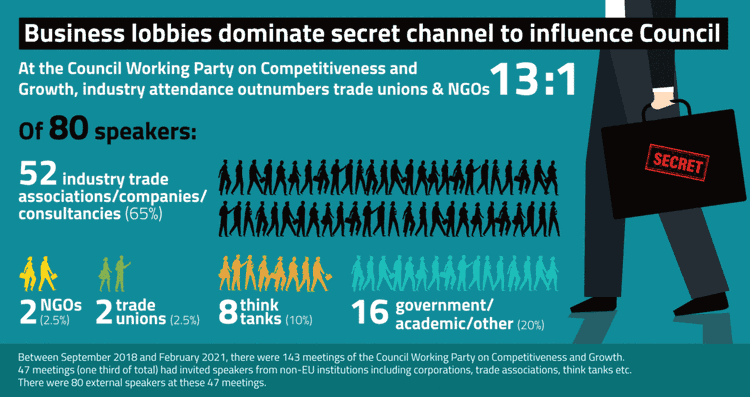

Analysis of this working party’s 143 meetings between September 2018 and February 2021 shows that business interests massively outnumbered trade unions and non-governmental organisations—by 13 to one—in attendance at these meetings. While industry held 65 per cent of the external speaker opportunities, alternative voices from trade unions and NGOs were rarely invited, with just 5 per cent of speaker slots.

BusinessEurope, representing Europe’s biggest companies, attended seven meetings, speaking on issues such as deregulation, artificial intelligence and the single market. Industry4Europe, Eurochambres, and the European Round Table for Industry also received invitations to speak. By contrast, the European Trade Union Confederation attended just one meeting.

Organisations with links to Big Tech have also been regular attendees. Microsoft, Apple, Facebook and Google are members of BusinessEurope, DigitalEurope and several other trade associations and think-tanks which have spoken at working-party meetings. Microsoft also attended a meeting directly. But no digital-rights organisation did so.

Dirty industries are found too on the invitation list, including the steel, metal, chemical, and cement industries, as well as at least one fossil-fuel company. Yet only one green NGO spoke during the period studied.

Having an impact

This bias towards corporate interests is deeply problematic. After all, these meetings provide lobbyists with a prized opportunity to present an organisation and its demands, often at very timely moments.

In March 2019, BusinessEurope addressed the working party, just as it was becoming clear that the proposed—but highly controversial—Services Notification Directive did not have enough support to pass into law. The directive had been successfully opposed by a coalition of civil society, trade unions, city mayors and progressive municipal political parties.

The directive’s supporters, including the European Commission and big business, were looking for alternative ways to introduce oversight and enforcement powers over decisions taken by national authorities and city councils on a vast range of services, from childcare to energy and water. A BusinessEurope demand, presented at the meeting, was implemented by the end of the year.

No dissenting views

Dissenting voices offering alternatives to the prevailing EU orthodoxy of ‘competitiveness’, ‘completing the single market’ and ‘innovation’ are not being heard by this working party.

A case in point is the EU’s controversial deregulatory drive, ‘Better Regulation’. BusinessEurope, an ardent supporter, has presented to the working party’s ‘Better Regulation’ sub-group on four occasions. It reported that one of its presentations was ‘well-received’ and stimulated a ‘constructive exchange of views’. Apparently, BusinessEurope argued for ‘regulatory simplification’.

Meanwhile the Centre for European Policy Studies think-tank spoke to this sub-group three times, including to present its study, commissioned by the German government, which looked at how to implement the controversial ‘one in, one out’ approach—a key element of the ‘Better Regulation’ agenda. The study has been criticised by the trade union movement.

‘Better Regulation’ is not simply technical and procedural—it represents a pro-corporate, deregulatory political agenda. But this council working party only hears from supporters of ‘Better Regulation’. It is not listening to trade unions and NGOs who provide a critical voice on associated threats to the environment and workers’ and consumer rights.

Behind closed doors

The council’s working parties have faced strong criticism from the European ombudsman, MEPs and civil society. They operate behind a veil of secrecy: while meeting agendas are published, no minutes are taken. In addition, lobbyists’ presentations to the Working Party on Competitiveness and Growth are not proactively published by the council and some invitees are not even part of the EU transparency register for lobbyists.

In July 2019 the council secretariat promised to issue guidelines on external speakers at working-party meetings. Two years on, these have yet to appear.

This council working party is offering a shocking degree of privileged access to big business to present its demands. It is another important part of the jigsaw of how corporate lobbies influence the work of the council and member states.

Those with private and commercial interests should not be favoured with special invitations to present their policy demands to member-state officials, tasked with developing council positions on important topics. It’s time to block this secret channel for corporate lobbyists, and for the EU institutions and member states to challenge the official mantra of ‘completing the single market’, as if this were merely technical—and so defending big business.

Vicky Cann is a researcher and campaigner with Corporate Europe Observatory.