The good news is minimum wages have risen across Europe this year. The bad news is inflation is eroding them.

Minimum wages have risen significantly in the European Union this year, as member states have left behind the cautious mood of the pandemic. Yet increasing inflation is eating up these wage increases—and only flexibility in the processes for setting minimum wages may avoid general losses in purchasing power among low earners.

On June 6th, the Council of the EU and the European Parliament reached a political agreement on the directive on adequate minimum wages, proposed by the European Commission in October 2020. Once formally approved, member states will have to transpose it into national law within two years.

The directive encourages the setting of wage floors at adequate levels in those countries (21 of the 27) with statutory minimum wages. Individual member states will set such a level, taking into account socio-economic conditions, long-term productivity trends and the purchasing power of the minimum wage.

Difficult task

The current picture across the EU illustrates how difficult this task can be. Policy-makers are challenged when setting statutory rates—as are the social partners when negotiating increases—in a context of inflation eroding purchasing power.

Increases in minimum wages between January 2020 and January 2021 were rather modest, with the pandemic compelling restraint. But all member states except Latvia increased their statutory rates between January 2021 and January 2022, and most countries did so to a greater extent than in the previous year. The median nominal increase across member states was 5 per cent (the mean above 6 per cent) and, as in the previous yearly interval, the increases were much larger in central and eastern Europe.

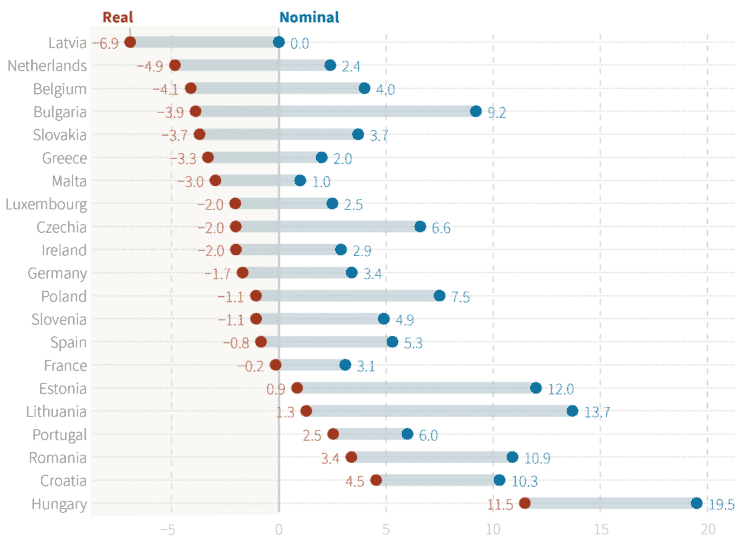

Nevertheless, these increases in nominal statutory rates have not generally boosted purchasing power among minimum-wage earners due to rising inflation, coming to the fore for the first time in many years in Europe. As a result, in real terms statutory minimum wages declined between January 2021 and January 2022 in more than two-thirds of EU countries. In only the six countries at the bottom of the figure below—several central- and eastern-European countries and Portugal—was there a real uplift. Indeed, if current inflation trends continue, barely any country will escape a deterioration in the purchasing capacity of its minimum wage as the year progresses.

Change (%) in statutory minimum wages, real and nominal, January 2021 to January 2022

Action needed

Action is needed. As it is unlikely that inflation will strongly subside this year, only determined policy interventions—by wage-setters or the negotiating parties—can secure the living standards of minimum-wage earners. This could mean additional increments to statutory rates, higher increases in negotiations or other support measures for the low-paid.

Only around half of member states with statutory minimum wages are legally obliged to take inflation or changing living costs into account when setting rates. The EU directive on adequate minimum wages could bring about significant change here: by requiring wage setters to use clear criteria, such as the purchasing power of the minimum wage, the directive will oblige them to take account of changes in the cost of living to maintain living standards among minimum-wage workers. It remains to be seen, however, how quickly wage setters will decide, or be able, to react when circumstances change.

Some member states with automatic-indexation mechanisms included in their minimum-wage setting process—such as Belgium, France and Luxembourg—have been quicker in uprating wages in line with inflation. For instance, two increases of 2 per cent each were triggered in Belgium in March and May 2022 as a result of indexation, following two identical increases in September 2021 and January 2022.

The directive will require those member states without such automatic indexation to update their statutory minimum wages at least every other year. Even though most have a yearly updating cycle already in place (and a few regularly uprate also within the year), for someone who is already financially stretched a wait of one to two years to see their purchasing power re-established can seem like an eternity.

Ad hoc interventions

It is thus important to maintain the possibility of ad hoc policy interventions in minimum-wage-setting processes, if such interventions are justified—as in this context of high inflation. For instance, Greece decided to upgrade its statutory minimum wage by more than 7 per cent from May 2022, outside the regular uprating cycle, due to inflation concerns.

How adequate the wages of minimum-wage earners will be at the end of 2022 will depend on the flexibility of the established procedures for statutory-minimum-wage setting and the political will to maintain the purchasing power of the lowest paid. It will also depend on the commitment of the social partners and their ability to arrive at negotiated outcomes that take inflationary pressures into account.