On March 10th, Silicon Valley Bank collapsed. Only 48 hours passed between announcement of its difficulties and evacuation of all investors’ accounts. The main cause was not high-risk investments in exotic derivatives, as in the financial crisis of 2008: SVB had put its money in United States government bonds, considered safe.

Rather, rapidly rising interest rates, imposed as part of the Federal Reserve’s anti-inflation policy, meant bond prices had fallen. The bank’s clients needed cash to meet their commitments and SVB had to sell securities at a discount to obtain it. The herd panicked and headed for the door.

The bankruptcy was orchestrated by the liquidation of Silvergate Bank and Signature Bank. The distress sale of the major Swiss bank Credit Suisse fuelled concerns of a spillover to the entire sector. Its looming insolvency could only be averted with massive state intervention.

If this indicated ‘dark spots’ in banking supervision, as the head of the Bundesbank put it, central banks’ monetary policy was also to blame. Almost weekly, chief economists of the European Central Bank and national central banks hold out the prospect of further interest-rate rises.

Quixotic strategy

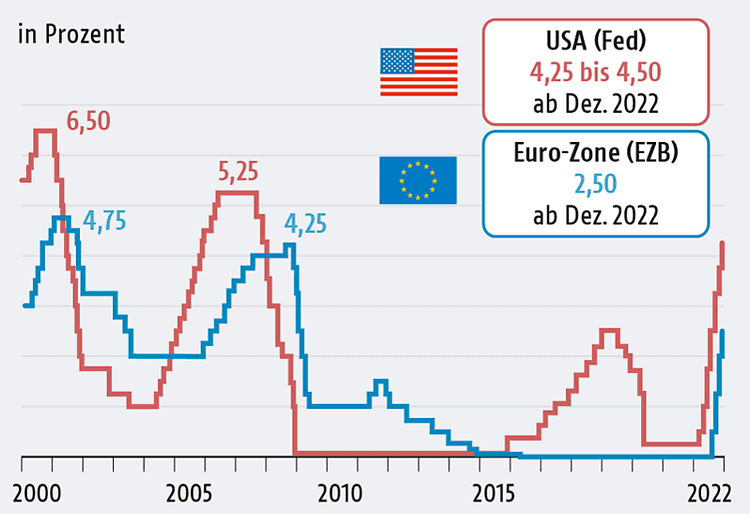

Since July 2022, interest rates have already been raised six times. The Bank of England raised its rate in February for the second time in two months, as did the Fed (Figure 1).

Figure 1: interest rates since 2000

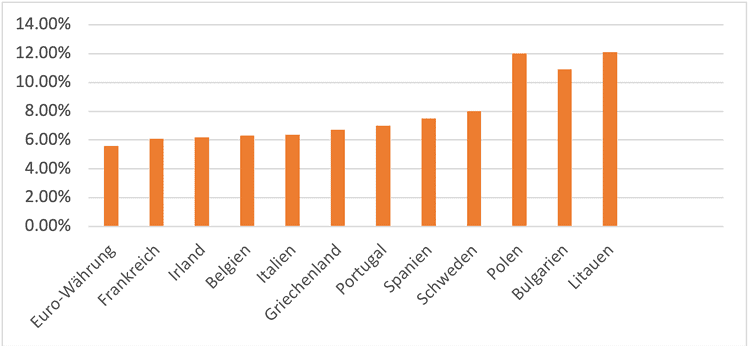

Nevertheless, inflation in the European Union is still more than three times the 2 per cent target of the ECB system (Figure 2).

Figure 2: core inflation in selected EU member states, March 2023

Apparently, the ECB assumes that any deviation from the path of interest-rate rises could be interpreted as indicating concern for Europe’s banks: its representatives never tire of assuring that these have solid capital and liquidity positions, even if their resistance to regulation has seen little uplift in the equity stake since before the crash. Yet EU member states face further increases in government debt, with interest rising on new borrowing while the price of the bonds they issue falls.

What is behind this quixotic strategy? The interest-rate hike is supposed to suppress inflation and bring about low, stable prices. But unemployment could rise, despite the reported need for skilled workers, while by increasing the cost of credit rising interest rates could still cause living standards to fall.

In the central banks’ view, price controls are good, but only for labour. In the United Kingdom unions were furious in February last year when the governor of the Bank of England—his remuneration package in excess of half a million pounds a year—called on workers to refrain from demands for wage increases.

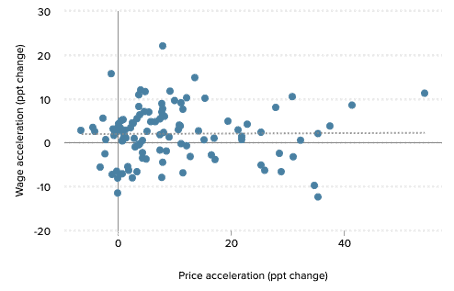

While this is socially brutal, it could be defended by an orthodox economist if inflation were a ‘wage-price spiral’—to borrow the language of the 1970s—in which wages, rather than prices, were moreover the driving force. There is however no correlation between wage growth and inflation (Figure 3) and wages are lagging behind price increases, which thus must be spurred by other factors as real incomes fall.

Figure 3: price inflation and wage growth across 110 US industries, December 2020 to November 2021

Short supply

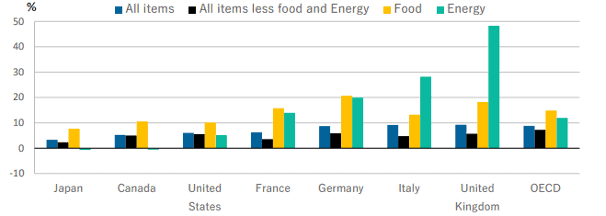

Current inflation has its roots outside the labour market. Joseph Stiglitz and Ira Regmi have shown it is supply- rather than demand-driven, due to supply-chain difficulties and sector-specific shortages of energy and agricultural products caused by the pandemic and the war in Ukraine (Figure 3).

Figure 4: consumer prices, G7 economies and OECD, February 2023, year-on-year inflation

Today, growing corporate profit margins—windfall profits—and high energy prices are drivers of inflation. We are therefore confronted with a price-profit spiral, in which curbing energy prices and rent-seeking behaviour would lower inflation.

Against this background, central-bank monetary policy cannot be effective: just because the Fed has a hammer, it should not use it to smash the economy. The stifling of necessary investments, including in green energy, is not unavoidable ‘collateral damage’. High interest rates also reinforce inequality: households with little wealth have net liabilities and are therefore disproportionately hit.

One has only to recall the ‘Volcker shock’ of 1980—the interest-rate rises under the then chair of the Fed, Paul Volcker, which precipitated the recession and unemployment of the early 80s. Today, rising inflation, high energy prices specifically and, yes, war provide a backdrop similar to the 70s. The shock therapy to combat inflation then lacked moderation and the ECB should follow a more balanced and innovative path.

Modernising the mandate

With its existing instruments the ECB cannot solve the structural problems of the euro area and the incompleteness of monetary union. The integration of monetary policy is inadequate to ensure the stability of the currency area when associated with strong fiscal decentralisation, economic disparities and political fragmentation.

At least the bank’s mandate has already been modernised in some respects, such as climate. This issue has recently been taken into account when assessing financial stability or the effectiveness of monetary policy. Unlike the Fed, however, employment remains outwith the ECB’s remit.

On the one hand, it seems difficult or even impossible to find a compromise among EU member states to revise the treaties so that price stability is not the only principal objective of monetary policy. On the other hand, the ECB’s mandate will be regularly reviewed in view of the changing economic environment, which is a welcome development at least.

More sophisticated monetary policy must be matched by well-calibrated fiscal policies on the part of the EU as well as member states. The Recovery and Resilience Facility could form the nucleus of a future common fiscal policy, beyond the ‘Maastricht consensus’.

Abuse of market power

To tackle excessive prices due to abuse of market power in whole commodity sectors—mineral oil, gas, grain—price controls and competition law are the correct instruments. Inflation is significantly lower in member states which have intervened directly on prices than those relying on offsetting income supports.

In Austria, for example, policy has been 25 per cent focused on price intervention, 75 per cent on income support: it has only applied a direct curb to electricity prices, the predominant measures including one-off payments. This places it at the bottom of the eurozone and unfortunately as one of the worst performers on inflation, still at around 9 per cent. In France, where the balance is the opposite—with 92 per cent reliance on price-setting measures—inflation is cooler at 7 per cent.

An innovative ECB monetary policy, promoting investment and employment, should thus be complemented by regulatory measures by member states. These should cap the price of gas, and decouple that of electricity from it, while also putting a ceiling on rents. Above all, super-profits should be skimmed off via competition law and an effective excess-profits tax.