Inflation, driven primarily by large and persistent increases in energy and food prices, is a great concern around the world. Policy-makers remain divided on how best to control it—though tight monetary policy seems to be gaining ground, despite its potentially harmful impact on fragile economic recovery.

Perhaps the most pressing challenge in the short term is to tackle the impact of the rising cost of living on households, which is seriously affecting increasing numbers and sparking street protests. At the European Union level, agreement within the European Council meeting in late June to go on to the front foot to curb rising energy prices—and hence their social impact—seems however to have proved hard to reach, leaving initiatives in the hands of individual member states.

Member states have resorted to several measures, including lowering taxes, regulating prices and giving vouchers to vulnerable households, while international organisations, such as the International Monetary Fund, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and the European Fiscal Board, clearly advise governments to target temporary support at the most vulnerable. In designing pro-poor policies to attenuate the distributional impact of inflation, insights may be gained from Greece—a member state facing one of the highest inflation rates in the euro area and just recovering from a decade-long economic crisis which has left big scars in terms of lost output, high unemployment and large-scale impoverishment.

Utmost importance

One insight from such a worst-case scenario is that empirical evidence is of utmost importance in designing policies. Policy-makers are readily aware that lower-income households face a heavier burden from inflation, as they already spend a greater share of their resources on necessities such as food and energy. But how much heavier?

The OECD reports that the increase in expenditure in eight member countries resulting from the surge in food and energy prices represents a larger proportion of total spending for low-income households. Compared with the highest income quintile, for the lowest the increment is between one and three percentage points greater, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom being the starkest instances.

Yet running a similar simulation for Greece suggests much harsher relative impacts still. We calculate the increase in the cost-of-living of Greek households using the 2019 Household Budget Survey (HBS) micro-database (to avoid distortions in consumption caused by the pandemic) and detailed price indices (for over 70 subcategories of food and energy items).

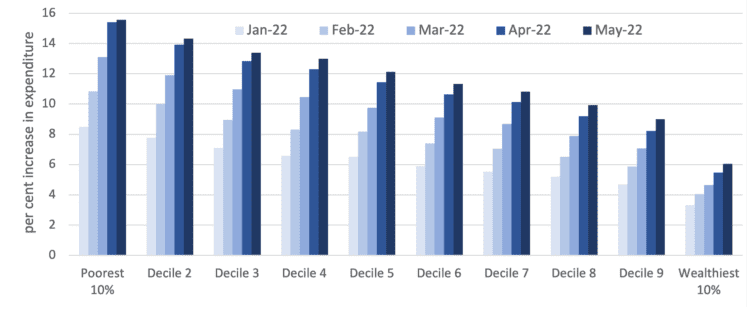

Greek households at the lower end of the distribution would need to increase their total spending by over 15.5 per cent to maintain their food and energy consumption at constant levels (Figure 1). The burden steadily declines throughout the distribution, with the wealthiest 10 per cent facing just a 6 per cent increase in their total spending to maintain their food and energy consumption. The distributional burden of inflation can thus be far worse than even that identified by the OECD in the UK and Dutch cases.

Figure 1: estimated impact of year-on-year increases in energy and food prices on a monthly basis by household expenditure decile

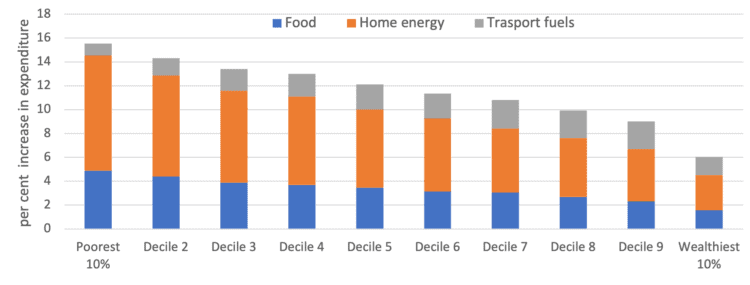

From a policy perspective, the design and magnitude of support measures towards the vulnerable have to take such evidence into account. At the same time, the data show that a substantial part of the impact of inflation feeds in through rising food prices (see Figure 2), while most government measures so far focus mostly on energy.

Figure 2: composition of increase in cost-of-living, May 2022

Market incomes

The inflation crisis lends support to influential thinkers such as the late Tony Atkinson, who in the context of the 2008 financial crisis called for a multi-pronged approach to support income redistribution. Government transfers are necessary, Atkinson argued, but insufficient to bring about desired outcomes, so governments should also intervene in how market incomes are first distributed.

In the Greek case, government-financed support—subsidies to electricity and natural-gas prices, one-off rebates on fuel costs and extraordinary transfers to vulnerable groups—is far from adequate. Simulations show, for instance, that for a household of two low-income pensioners both eligible for government transfers, such support would cover less than one-third of the total increase in their cost of living by May 2022.

In this context, rising minimum wages in Europe are no doubt good news in an age of inflation. Taking again the Greek example, the rather substantial 7.7 per cent increase in the minimum wage enacted from May 1st will partly shield vulnerable groups from price increases.

According to simulations of HBS data, however, a family with two children and one parent working at the minimum wage, with living standards in the poorest decile, would require a 27 per cent increase in the minimum wage just to stand still, due to surges in food and energy prices. If the same household were to enjoy living standards corresponding to the Greek average, the increase in the minimum wage would have to be 43 per cent.

Opportunity to rethink

Government transfers to the vulnerable and rising minimum wages are both welcome in addressing inflation from a pro-poor standpoint. Yet the Greek simulations show that increased transfers are unlikely to be sufficiently generous nor minimum-wage increases adequately protective of even the most vulnerable facing the impact of rising inflation. This even though we assume full take-up of benefits—an assumption belied by reality.

The inflation crisis is an opportunity to rethink how the reinforcement of redistributive policies should be combined with policies securing stable, well-paid jobs and the fair sharing of the gains of a growing economy. In view of the massive NextGenerationEU investment plan, aspiring to transform EU economies, this vision is not beyond the power of national governments or EU institutions. To rephrase Atkinson, the latter should make sure that the rising tide lifts all boats—so that the ebbing tide does not leave scars on society.

Georgia Kaplanoglou is professor of public finance and social policy at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. Previously, she worked in the Economic Research Department of the Bank of Greece, representing the bank in working groups of the European Central Bank and the OECD on public-finance issues.