Economic growth is slowing sharply due to Russia’s war in Ukraine and the related inflation shock. Many of the hardest-hit countries are in Europe, highly exposed through energy imports and refugee flows.

During the pandemic, short-time working was Europe’s success story to protect jobs and incomes against lockdowns, but these schemes have been phased out in most countries. It is time to overhaul the crisis toolbox and prepare for the next recession, to avoid a sudden spike in unemployment. Governments should learn from the prior policy innovations, sharing best practices while tailoring them to their specific situation.

Preserving relationships

Job-retention policies aim to maintain employee incomes and sustain firms through a recession. Such labour-hoarding measures help preserve the employment relationship and sustain consumer demand, facilitating a rebound during a subsequent recovery. Sustaining the employment relationship preserves firm-specific skills—the ‘great resignation’ shows the costs of hiring and training new staff—and acts as an insurance policy against unemployment during a demand crisis.

During the major lockdown of 2020, Europe learnt from the experience of the 2008 financial crash by scaling up and extending job-retention schemes—in the depth of the recession then, just 1.5 million were so protected. Consequently, in contrast to the United States, during the first Covid-19 wave the European Union experienced no rapid increase in unemployment. In April 2020, one in five employees in the EU were covered by short-time work, amounting to 42 million people.

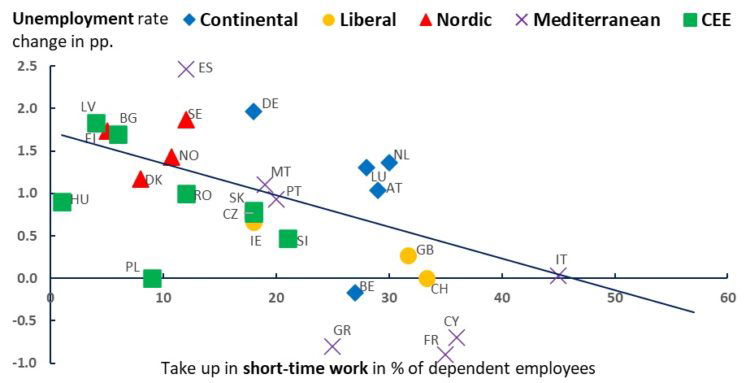

European policy-makers used job retention as a specific economic- and social-policy response to the crisis-induced employment shock, as we have shown in a comparative analysis. Across Europe (see chart), welfare states with higher take-up of short-time working experienced lower increases in unemployment. Initial estimates indicate that job losses would have been 50 to 100 per cent higher without job-retention measures. The effectiveness of short-time-working schemes however varied among countries.

Increase in national unemployment rate (Q3 2019 to Q3 2020) by take-up of short-time working (April/May 2020) and welfare model

Design choices matter for the effectiveness of job-retention policies: countries offering limited labour-cost subsidies to businesses on average benefited less from short-time working. Nordic welfare states continued their tradition of strong social protection for workers but refrained from generous firm subsidies. Combined with already fluid labour markets, employers had relatively little incentive to furlough workers. Central- and eastern-European (CEE) countries with few exceptions improved their otherwise residual support through short-time working but had lower take-up rates than elsewhere.

In contrast, higher firm subsidies, combined with more stringent employment protection, in continental and Mediterranean welfare states led to higher take-up of short-time working, expanding on already-successful past approaches. Liberal welfare states, especially the United Kingdom and Switzerland, embarked on a new path in their policy response. After introducing a widely-used model of labour hoarding, the UK government found itself unable to wind down the expensive job-retention scheme for more than a year. As a consequence, continental, Mediterranean and liberal welfare states spent on average four times more on job retention than Nordic and CEE countries, the latter group risking higher unemployment.

Preparing for recession

Three aspects have proved important in making job retention work at scale during the pandemic: design, preparation and funding. Policy-makers should focus on getting these right in preparation for the next recession.

Design:during the pandemic, short-time working was successful in reducing costs for employers while increasing generosity for workers. It is important to broaden the coverage to all sectors, non-standard workers and the self-employed. Administrative procedures need to be simplified and maximum duration extended to make job retention attractive.

Preparation: continental, Mediterranean and Nordic welfare states often relied on existing instruments, which were adjusted, while most liberal regimes and CEE countries had to set up new schemes, often introducing ad hoc wage subsidies. Social-partner involvement was key to the emergency response. Governments should consult with the social partners, aiming to sign tripartite agreements with employer associations and trade unions to implement job retention.

Funding: significant funding was important to signal the generosity and sustainability of job-retention policies. For countries with limited financial capacity emergency EU funding was crucial, from unused cohesion funds, the SURE employment-protection programme and eventually the recovery plan, NextGenerationEU. EU support helped Mediterranean and CEE governments in particular to ramp up borrowing and so spend more on employment protection during the crisis. This time, elevated inflation is putting pressure on public finances, but fiscal space should again be made available in case of a severe recession.

Job retention was of tremendous help in mitigating the labour-market impact of the pandemic in Europe. Important lessons should be learned from the experience of these past years to design the next crisis response. Governments and social partners need to prepare their policy toolbox for a slowing economy.