Convergence of central and eastern-European EU members towards older ones with high minimum wages is much stronger than in the Mediterranean countries.

The dilemmas for decision-makers setting 2021 minimum-wage rates were aggravated by the pandemic. Their usual concerns, to strike a balance between adequate wages for the lowest-paid and safeguarding jobs and businesses, were amplified by the challenging economic outlook: growing unemployment, downward pressure on wages and huge uncertainty. The disruption to normal negotiation and consultation processes, caused by the virus-containment measures, exacerbated these challenges.

Were statutory minimum-wage adjustments affected by this troubled economic situation? To some extent, yes: while rates have risen in 2021 across most countries, the magnitude of the rises has been lower than for a year ago.

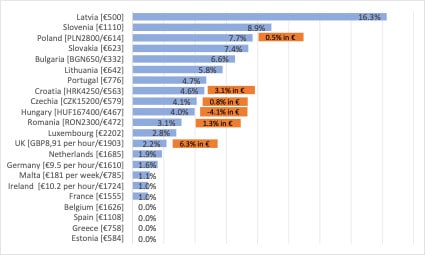

Figure 1 presents data on gross statutory minimum wages in 2021 and their growth rates (calculated in national currencies) between January 2020 and January 2021. Among these 21 European Union countries (plus the UK) with statutory minimum-wage systems, rates have risen in all but four: Belgium, Spain, Greece and Estonia.

Figure 1: statutory minimum wages in 2021—levels and growth rates

In six central- and eastern-European countries, minimum wage rates have increased by more than 5 per cent: Latvia, Slovenia, Poland, Slovakia, Bulgaria and Lithuania (although progress in Poland would be modest if rates were calculated in euro). A lower increase has been registered in several older member states—Portugal, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Germany, France and Ireland—and some that joined the EU in 2004 or later: Croatia, Romania, Malta, Czechia and Hungary (although the latter’s minimum wage fell in euro terms). As for the UK, its 2.2 per cent increase in sterling would have exceeded 6 per cent if rates were calculated in euro.

More modest

Despite these generally positive developments, minimum-wage rises for 2021 were more modest than for 2020. The median minimum-wage increase in 2021 was 3 per cent (in national currencies), whereas for last year it was 8.4 per cent and all countries but Latvia recorded increases. Furthermore, the differences in minimum-wage rates across EU countries reduced only somewhat in 2021.

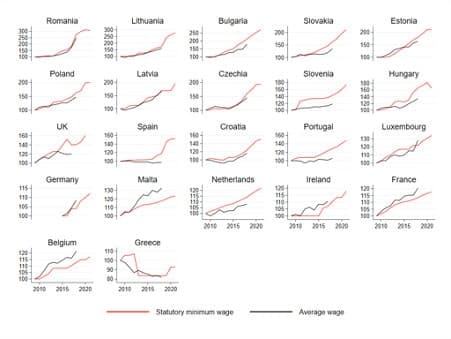

How have minimum wages evolved in recent years? Figure 2 depicts this evolution and that of average wages from 2009 to the most recent year for which data are available (2021 for minimum wages and 2018 for average wages). The data are indexed (2009 = 100), and countries are ranked by the magnitude of their minimum-wage growth over the period—from Romania, where minimum wages tripled, to Greece, the only country where minimum wages declined.

Figure 2: evolution of statutory minimum wages (2009–21) and average wages (2009–18), 21 member states and the UK

Although progress on the two indicators tends to go hand in hand, statutory minimum wages have increased faster than average wages in more than two-thirds of countries, which means the lowest-paid employees have experienced higher wage growth than the average. Among these countries, the central- and eastern-European member states stand out for the exceptional growth in their minimum wages: Romania, Bulgaria, the three Baltic countries, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia and Czechia.

In other countries, where increases were smaller, their growth is still very much above that observed in average wages; these include Spain (especially after the 2019 increase), Portugal, the UK and Slovenia. Greece is the only country where minimum wages fell—although average wages declined even further.

At the other extreme, however, there is a small group of six countries where rises in the statutory minimum wage have not kept up with growth in average wages: Belgium, Germany, France, Ireland, Luxembourg and Malta.

Strongly converged

Member states have thus strongly converged in their statutory minimum-wage rates (as well their average wages) over the last decade. On the one hand, growth has been modest among the older member states with the highest minimum wages: Belgium, France, Germany, Ireland, Luxembourg and the Netherlands. On the other, there has been remarkable progress among countries with the lowest rates, which have at least doubled over the period: Romania, Bulgaria, the Baltics, Hungary, Slovakia, Poland, Czechia and, behind them, Slovenia and Croatia. This convergence is evident in data on nominal minimum wage rates but it is even stronger after correcting for differentials in economic conditions and price levels.

Unlike the central- and eastern-European countries, however, the Mediterranean member states have failed to catch up significantly with those countries with the highest minimum-wage rates. Greece is a particular case in point: its minimum wage was cut in 2012 and subsequently frozen, albeit there were increases in 2019 and 2020. And the Portuguese and Spanish minimum wages have only converged modestly, although the notable increases in Spain in recent years, especially in 2019, provide a much more positive note.