Racism is nothing new: people who look, speak or behave differently have always been a target. But this age-old practice of ‘othering’ is getting worse.

A report by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA), Being Black in the EU, reveals that racism against people of African descent is on the rise across Europe. Drawing on interviews with more than 6,700 people, the research documents the extent to which they experience discrimination and hate crimes in their daily lives.

There has been no improvement since the last such survey in 2016. Racism remains insidious and relentless—indeed in many places it is getting worse.

Discrimination and harassment

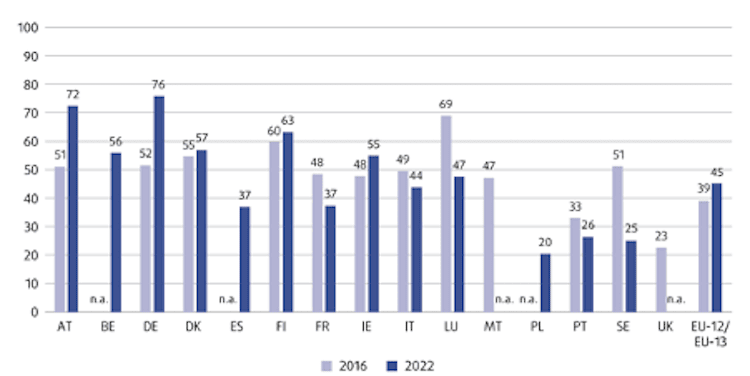

Almost half (45 per cent) of those of African descent surveyed in 2022 had experienced racial discrimination in the previous five years—up from 39 per cent in 2016 (Figure 1). In two countries, Austria and Germany, this exceeded 70 per cent. Yet discrimination remains invisible, as only 9 per cent of those affected report it to any official body.

Figure 1: prevalence of racial discrimination in the five years before the survey, by country and survey year (%)

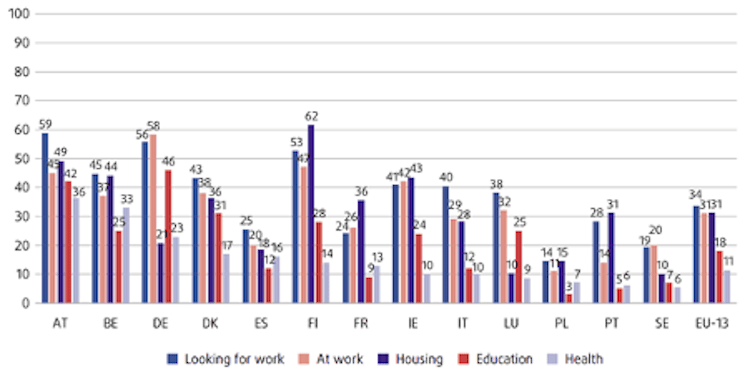

Nor are experiences of racial discrimination isolated episodes: they happen repeatedly and in many areas of life—most often when looking for a job, at work and/or when searching for a home (Figure 2). Over half (55 per cent) of those experiencing discrimination in the year before the survey had suffered this more than three times.

Figure 2: prevalence of racial discrimination in different areas of life in the five years before the survey, by country (%)

People of African descent in the EU are less likely to land a job interview, let alone a well-paying job, compared with the general population. Even if they have higher education, they very often work in positions far below their qualifications. They struggle to find suitable homes, often left to live in overcrowded apartments in socially marginalised districts. This has a knock-on effect on all areas of their life, perpetuating the cycle of discrimination and inequality.

Levels of racist harassment and violence are equally disturbing. Almost one in three respondents (30 per cent) had experienced racist harassment in the five years before the survey. Most worryingly, this can start very young: 23 per cent of parents said their children had suffered racist harassment and bullying at school—again an increase since the last survey. And, once more, almost no one reports it, denying victims the support of the institutions meant to protect them.

Pushed to the edge

The figures are similar when we consider other ethnic or religious minorities: Roma and Travellers, Muslims and Jews.

Roma and Travellers are pushed to the very edges of our society. They face unacceptable deprivation, marginalisation and discrimination, reflected most strikingly in the differential in life expectancy: on average a Roma person in the EU dies ten years younger than others.

Members of Jewish and Muslim communities meanwhile experience a compounding of racial and religion-based discrimination. When FRA asked Jews in 2018 about the biggest problem in their life, almost 90 per cent said it was anti-Semitism. As we watch with horror what is happening in the middle east, we observe how that awful situation is exacerbating expressions of racism and hatred against Jewish and Muslim communities in Europe.

Pernicious legacy

Why, despite binding EU anti-discrimination law, do people continue to face racism, discrimination and hate crimes? First, we need to recognise the pernicious legacy of colonialism. Colonialism has had a profound impact on societies, providing a powerful foundation for prejudices and inequalities. Its models and assumptions of racial superiority still endure.

Closely related is systemic racism. The persistent experiences of racism across the EU point to deeper, more structural issues. Acknowledging that racism seeps into all our systems, rules and institutions is the only way to begin to confront its endemic nature.

Then we need to look at the racialised way in which irregular movement of people to Europe is discussed. With arrivals increasing, we need to consider the impact of extreme ideologues, whose voices are increasingly amplified. The fears they stoke are often exploited for quick political gains, further dividing our societies.

FRA’s research shows that the quality of public discourse matters. For example, its LGBTI survey shows that the situation for LGBTI people only deteriorates when public figures, politicians and parties adopt a negative stance. When the society is unsupportive and laws are not enforced, discrimination increases.

We saw this during the pandemic, when leaders in some European countries accused Roma of spreading the virus, putting whole communities under stricter lockdown. And Russia’s aggression against Ukraine saw anti-Semitic rhetoric translate into anti-Semitic behaviour, especially online.

In difficult times, members of minority groups become targets. And ‘social media’ only make it easier to spread hateful messages across borders.

Collective problem

So what can we do to tackle racism? We must first recognise that this is not a problem of the affected groups: it is our collective problem.

Discrimination based on ethnic origin is illegal under EU law. Member states approved the racial-equality directive over two decades ago. But they have to enforce it properly to make it a reality.

Everyone, regardless of origin, faith or physical characteristics, is entitled to the same fundamental rights across the EU. Member states have duties to protect, respect and fulfil those rights. Political leaders cannot treat minorities differently—using them as scapegoats—whenever things get difficult.

The EU action plan against racism 2020-25 is a step in the right direction. But to make it effective, all countries must adopt national action plans and put in place measures to address discrimination in education, employment, housing and healthcare. This includes properly resourcing national equality bodies, so they can tackle racism and support victims. It also involves addressing discriminatory practices among the police.

EU countries must also properly identify, record and count hate crimes. Racial motivation should be recognised as an ‘aggravating’ factor in the determination of penalties and enforcing judgments.

Dealing with racism online entails striking the right balance between protecting people against illegal hate speech and protecting others’ freedom of speech. FRA’s new report on online content moderation provides policy-makers with evidence and guidance.

Finally, we cannot hope for lasting change if we work only for the affected communities and not with them. This must be done in partnership—otherwise, we won’t see any progress.

Tackling the scourge of racism is going to be a long fight. But a society where everyone is free and equal in dignity and in rights is within our grasp.

Michael O’Flaherty is director of the EU Agency for Fundamental Rights. Previously, he was professor of human-rights law and director of the Irish Centre for Human Rights at the National University of Ireland, Galway, chief commissioner of the Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission and a member of the UN Human Rights Committee.