The report by Mario Draghi on the future of competitiveness (together with Enrico Letta’s report on the Single Market) is a landmark publication poised to shape the agenda of the incoming European Commission. According to Draghi, the foundations of the European economic growth model are under strain. World trade expansion is in decline, the era of cheap Russian gas has ended, and new security concerns call for a fundamental policy overhaul. To meet the challenge, 800 billion in public and private investment must be mobilised. Simply put, European policymakers must shift paradigmatic gears in governing the economy if the EU wants to remain relevant amidst intensified economic and political competition between China and the USA.

From a welfare state perspective, the report represents a significant step forward in considering the relationship between economic growth and social policy in positive terms. The strong emphasis on productivity through knowledge and skills, moving away from the narrow focus on (gross unit labour) cost-competitiveness that dominated the early years of the Great Recession, brings back into view the notion of social policy as a productive factor. However, we believe that Draghi’s plea to ‘preserve’ the European Social Model is unnecessarily defensive, as if competitiveness and productivity fall outside the purview of European welfare states in times of accelerating ageing and increased geopolitical competition. They do not: economic prosperity is a function of productivity and employment, which is precisely what a robust welfare state supports.

The Draghi report would have benefited from a more engaged reading of the 2023 high-level group report The Future of Social Protection and the Welfare State, commissioned by the European Commission (hereafter HLG-Report). Draghi may be concrete on the ‘money question’ of billions of private and public investments, but the report is somewhat imprecise on the ‘people question’ of those who need to be mobilised and how. In addition, the report is relatively narrow regarding questions of governance. Draghi recognises that Europe’s working-age population is set to decline by 25 – 30 million workers in the coming years but falls short of offering a comprehensive solution. Demography is not destiny. In this contribution, we argue that an effective welfare state to support Europe’s untapped labour potential through inclusive employment with greater autonomy for dual-earner households and better work-life balance is critical to delivering a more competitive and prosperous European Union. We also question Draghi’s proposal to trim down EU economic governance.

Recasting the narrative on welfare spending and economic growth

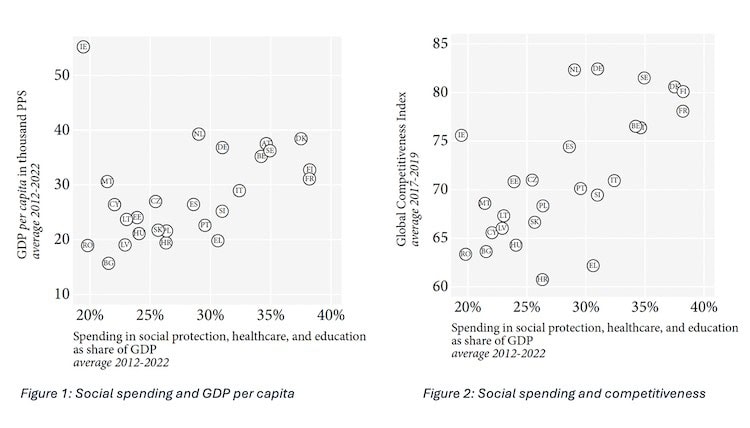

To demonstrate what kind of welfare state is needed to support a more competitive economy, it is first essential to counter popular misconceptions about the relationship between welfare spending and economic growth. Population ageing – rising life expectancy and falling fertility – indeed puts additional fiscal pressures on public expenditure. For far too long, the debate on ageing populations has focused heavily on savings to bring down unit labour costs, fiscal deficits, and old-age dependency ratios. One of the clear policy lessons of the Great Recession is that fiscal consolidation – especially in Southern Europe – effectively deepened the recession. The misguided assumption of a supposed trade-off between welfare spending and economic growth precluded social investment reforms needed to update welfare models to support productivity and labour force participation. It is imperative to acknowledge that there is no negative relation between social spending and economic growth or competitiveness; quite the opposite. As shown in Figures 1 and 2 below (we are grateful for the support of Daniel Alves Fernandes of Leiden University in compiling all figures), Europe’s big welfare spenders do better on growth per capita and score better on competitiveness indicators precisely because they support productivity and employment.

What matters for a better understanding of the relationship between social spending and economic growth is not the size of the expenditure but its composition. In this respect, as we will show in our forthcoming book, EU Member States differ enormously. Those with high employment and high competitiveness, like Denmark or the Netherlands, spend roughly equal shares of their social spending on the young (e.g. education and childcare), the working class (e.g. social protection) and the elderly (e.g. pension spending and long-term care). For Greece or Italy, roughly two-thirds of all social spending is for the elderly, leaving little space to invest in children, support dual-earner families or support the unemployed.

High employment and high productivity go hand in hand with a welfare model based on investing in the young and supporting dual- and single-earner families. This strategy effectively sustains current commitments to the elderly regarding pensions and care. In other words, there is a vast untapped potential for improving economic progress and social well-being across the EU.

The challenge for European labour markets to adjust to demographic ageing is momentous yet manageable. In demographic projections, it is commonly predicted that ‘old age dependency’ (the ratio of working-age people to those younger and older) will deteriorate in the decades ahead. Invoking a thought experiment, the HLG-report conjectures that this ratio would remain unchanged if the employment rate would trend up to about 85% and if, at the same time, the average retirement age were to rise to 70 years. It is important to underline that these conjectures are not unrealistic, given that today, some member states reach levels of employment close to 80% and voluntary late retirement above the official pension age is common. While labour shortages are becoming more pronounced, roughly 21 per cent of Europe’s workforce remains inactive. European Commission services estimate that bringing all Member States on par with Europe’s top performers would support 17 million women, 13 million elderly or 11 million low-skilled into the labour market (categories overlap). However, to achieve this, welfare states will require transformative change. This is where the policy paradigm of social investment, the core policy recommendation of the HLG, gains purchase.

The social investment-oriented welfare state

In ageing societies, the long-term strength of the knowledge economy is ever more contingent on the contribution that social policy can make to the productive economy. This is best understood by taking a life-course perspective. Secure retirement critically depends on how people fared during their working lives, which, in turn, is strongly correlated with the quality of their childhood years. Effectively, there is a ‘life course multiplier’ logic at work, whereby cumulative social policy returns, reaped over the life course, generate a cycle of well-being in terms of higher employment, gender equality, lower intergenerational poverty, higher productivity and growth, and improved fiscal sustainability.

The cycle initiates with early investments in children through good-quality early childhood education and care, which translates into better educational attainment. This, in turn, spills over into higher and more productive employment in the medium term. To the extent that employment participation is supported by work-life balance policies, including affordable childcare and generous parental leaves, this narrows gender gaps in wages and employment, as dual-earner households offer better protection against child poverty. Investing in active and healthy lifestyles, greater access to training and more flexible retirement options make it possible for older people to work longer. Altogether, these policies reinforce higher and more stable and productive employment over the life course, thus supporting a more extensive tax base to sustain overall welfare commitments. In short, the basic logic of ‘the social investment welfare state’ is that to maintain pensions, it is a prerequisite to invest in children!

The logic of the social investment welfare state moves away from the classic conception of the welfare state as primarily serving redistribution. It starts from the basic truism that we all rely on welfare support at different stages in our lives for reasons of health, education, childcare, spells of unemployment, retirement, and old-age care. With welfare beneficiaries being mostly transitory categories, it is more fruitful to analyse how welfare provision dynamically interacts with family demography (gender, fertility), education, and skill formation (effective labour supply and productivity) in relation to the future tax base, especially in times of adverse demography.

From the redistribution angle, a common criticism is that social investment reform would redirect spending away from classic social protection programmes and/or dis-proportionately benefit the already well-off middle classes (so-called Matthew effects). However, as we have shown in a recent report, this is another misconception; countries that do better on social investment also do better on most equity indicators. Adequate and inclusive safety nets are part and parcel of the social investment welfare state and even a precondition for its success. The COVID-19 pandemic served as a stark reminder that safety nets are crucial to preserve demand and employment to allow countries to bounce back swiftly.

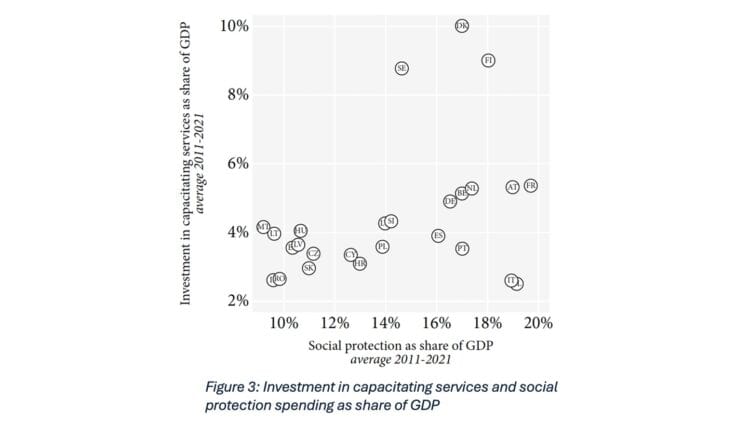

Furthermore, as we show in Figure 3, there is no trade-off between spending on capacitating services (including childcare, education and training, active labour market policy, active ageing, and long-term care) and classic social protection spending (on unemployment benefits, social assistance, family benefits, and pensions). Countries that spend more on capacitating social services also commit more resources to social protection.

Finally, social investments, like all investments, bear their fruits in the medium term while needing immediate resources to finance them. This brings us to our second reservation with the Draghi report concerning governance.

Embedding social investment in Europe’s economic governance

While we agree with Draghi’s diagnosis regarding challenges and opportunities, the governance analysis is less convincing. Draghi argues that the European Semester for policy coordination has proven too bureaucratic and largely ineffective and should, therefore, be replaced by a new Competitiveness Coordination Framework focusing on EU-level strategic priorities, with only budgetary rules remaining. We beg to disagree. Over the years, the European Semester has gained intellectual authority in welfare reform guidance in the direction of social investment. The Semester has become a social learning vehicle to foster political ownership with feedback monitoring on reform priorities. While national politics holds primacy in getting reforms over the finish line, Semester’s reform recommendations and reports have, in important ways, shaped and codified the social investment policy turn across Europe. Particularly since the introduction of the EU’s Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), recommendations have been backed up by even stronger domestic commitments conditioned by EU financial resources to deliver.

Stripping down the Semester to bare fiscal rules would interrupt the social learning process that has been activated in recent years by explicitly linking fiscal rules to public investment and structural reform to achieve medium-term budgetary sustainability. Last March, for the first time, a joint ECOFIN-EPSCO Council meeting met to discuss the potential of social investments to boost economic growth and productivity, much to the merit of the Belgian (and Spanish) Presidency, which – as shown by Vandenbroucke et al. – acted as important agenda-setters. However, there is a need to go further in integrating social investment priorities in the EU fiscal framework.

Hawkish Member States legitimately fear that by labelling (some) social policies as investments, the spending floodgates would come down. On the other hand, if budgets allocated to capacitating social policy continue to be treated purely as a cost, fiscal policy will ignore the positive employment effects of life-course sensitive social investment reform critical for European prosperity and well-being. What is more, the time bomb of adverse demography is ticking. Without social investment now, budgetary strains will only intensify in the medium term. As a first step, the Council has decided on a coordinated effort to measure the returns on social investment. Still, the social investment transition – guided by Semester recommendations – will eventually have to become part and parcel of fiscal-structural plans and debt sustainability analyses. If not, Draghi’s extra billions may go unspent as no qualified personnel can do the work.