During the pandemic, working from home has experienced an unprecedented boom. According to many observers, the associated changes in work organisation and processes will frame the work of the future. ‘Hybrid’ working at different, self-chosen locations—in the office, at home, on the road—is set to become the ‘new normal’ of the working world.

In addition to better protection against infection, working from home can have other advantages from the employee’s point of view. Avoiding travel can save time. And greater flexibility in planning and scheduling work can increase individual freedom of action and make it easier to reconcile work and private life.

Widespread desire

Various surveys indicate that most employees who have worked from home would like to retain this option even after the pandemic has ended. Very few, however, would like to shift their place of work completely to their own home.

There is a widespread desire to be able to decide the location flexibly, as the situation demands, whether to work in the company or from home. Human-resources managers in many companies are finding themselves challenged to advertise the possibility of location flexibility in the competition for sought-after skilled workers.

Does this ‘new normal’, as a side-effect, promote the trade union demand for more self-determination by employees over their working hours? Do the changes mean a gain in working-time sovereignty—at least for those employees who can work from home?

The annual Good Work Index published by the Deutscher Gewerkschaftsbund (DGB), the German trade union federation, helps answer these questions. In 2021 6,400 employees in Germany were interviewed for this representative employee survey. Two reference groups were formed: employees in the ‘new normal’, who communicate digitally and often work from home, and those in the same occupational groups who work predominantly in a fixed workplace—referred to here as the ‘former normal’.

Contradictory results

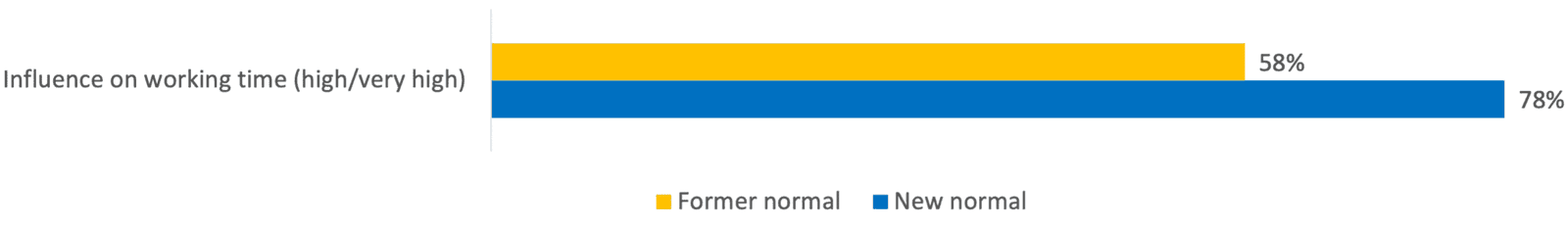

The survey results highlight the contradictory nature of work in the ‘new normal’. Employees who frequently work from home do enjoy greater self-determination over their working time: 78 per cent say they can influence it to a (very) high degree, which is true of only 58 per cent in the ‘former normal’ working world (Figure 1).

Figure 1: workers´ influence on the organisation of their working time

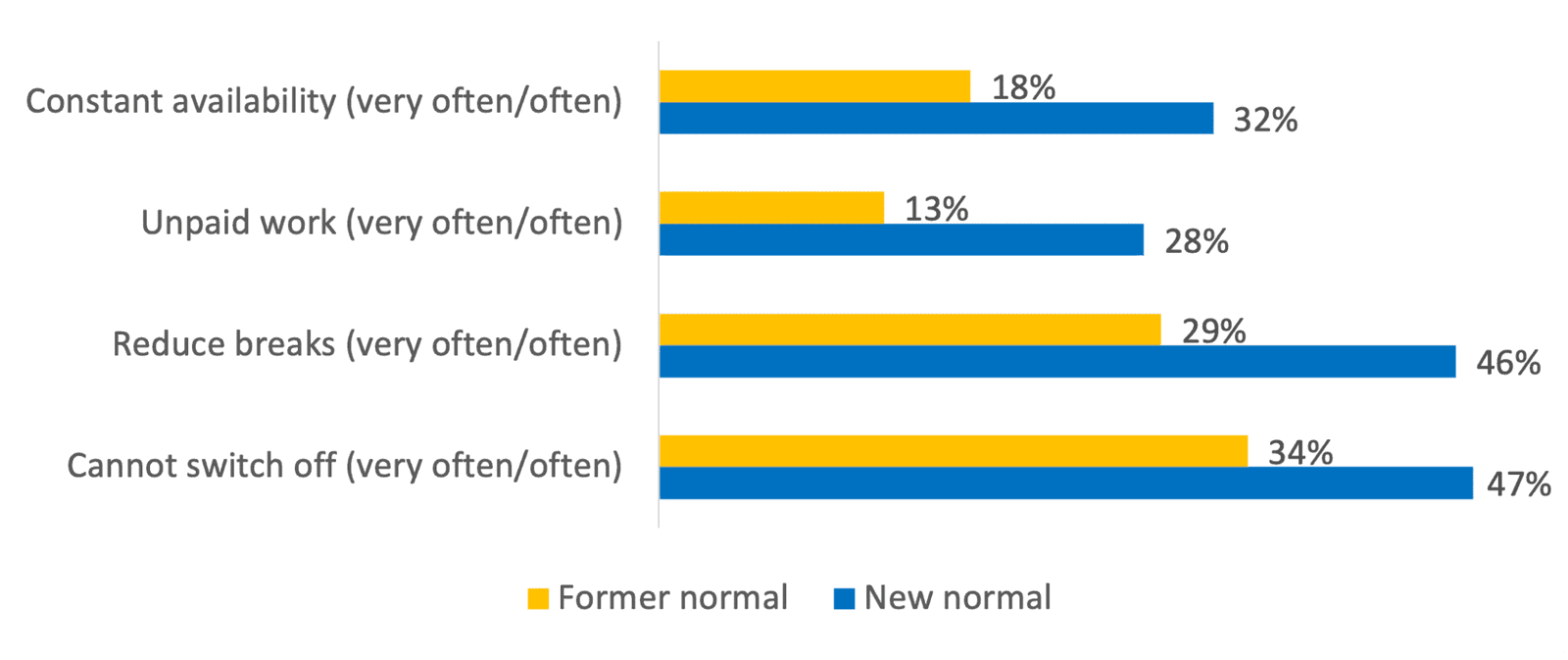

At the same time, the working hours of employees in the ‘new normal’ are much more unconstrained. One third (32 per cent) have to be frequently available for their employer even in their free time—in the ‘former normal’ this applies to only 18 per cent. In addition, employees in the ‘new normal’ work outside their regular working hours without pay much more frequently (28 per cent) than employees who cannot do their work from home (13 per cent). And in the ‘new normal’, almost half (46 per cent) say they often shorten their breaks, while only 29 per cent in the ‘former normal’ do so (Figure 2).

This loss of constraint on work when it comes to time has psychological corollaries. For effective recreation, it is necessary to be able to detach oneself from work-related matters in one’s leisure time. Almost half (47 per cent) of employees in the ‘new normal’ however often cannot do this. In the ‘former normal’, only one third (34 per cent) have problems with mentally switching off from work.

Figure 2: dissolution of working time

The ‘new normal’ is thus not only characterised by a loss of physical demarcation between work and the private sphere. The temporal and mental boundaries are also being dissolved.

Work without limits

Why, despite greater self-determination over working time, do those in the ‘new normal’ more often work without limits? The data show that the more time and deadline pressure there is at work, the more often one works beyond the old boundaries in the ‘new normal’. While the proportion of those who often work unpaid in their free time is between 10 and 18 per cent, when working very often under time pressure this rises to half (49 per cent).

The loss of constraint in the ‘new normal’ is thus less an expression of a self-determined organisation of working time and more the result of an excessive workload. It is true that the removal of boundaries is also increasing among employees in the ‘former normal’ when they are working under heavy time pressure—but it is much less pronounced there.

The organisation of working time is always linked to determination of the amount of work and its goals. Self-determined working hours which genuinely increase flexibility for employees are only possible with realistic performance measurement.

The removal of boundaries in the ‘new normal’ is facilitated by the loss of the physical boundary between work and free time. Work is no longer terminated by leaving the workplace; mobile devices or the workroom in one’s own home make it possible to return to work at any time.

Arrangements undermined

Arrangements that have been established over decades to protect employees from excessive stress and health risks are often undermined in the case of mobile working. Standards of working-time organisation and its recording are neglected. This is less noticeable because the way work is done at home remains invisible to company representatives, colleagues and superiors. The design of good working conditions in the ‘new normal’ therefore raises new challenges.

At the beginning of the pandemic, the work of many employees was often shifted to within their own four walls at short notice and without much preparation. Questions of working hours, technical equipment or ergonomic design often fell by the wayside. It is time to learn from this experience. For a healthy work design in the ‘new normal’, it is not enough just to hand employees laptops and smartphones: the standards of humane work design must also apply.

An important step is to create a legal framework defining the conditions and limits of remote work. The aim would be to strengthen the actual self-determination of workers over their place and time of work. Within such legal ‘guard rails’, design of the ‘new normal’ could be concretised in specific organisations through arrangements subject to collective bargaining. The data from the DGB’s Good Work Index also show that the loss of constraint on work is much less pronounced if company regulations on working from home have already been agreed.

The early and comprehensive participation of the workforce and workplace representatives is a prerequisite for overcoming the invisibility of work in the domestic context. Working in the ‘new normal’ is not a programme per se to humanise it. Only by strengthening the rights of employees and concrete design with the participation of those affected can it actually be used to enhance self-determination.

Rolf Schmucker is a social scientist and head of the DGB Good Work Index institute in Berlin. The institute conducts annual surveys of workers in Germany about their conditions.