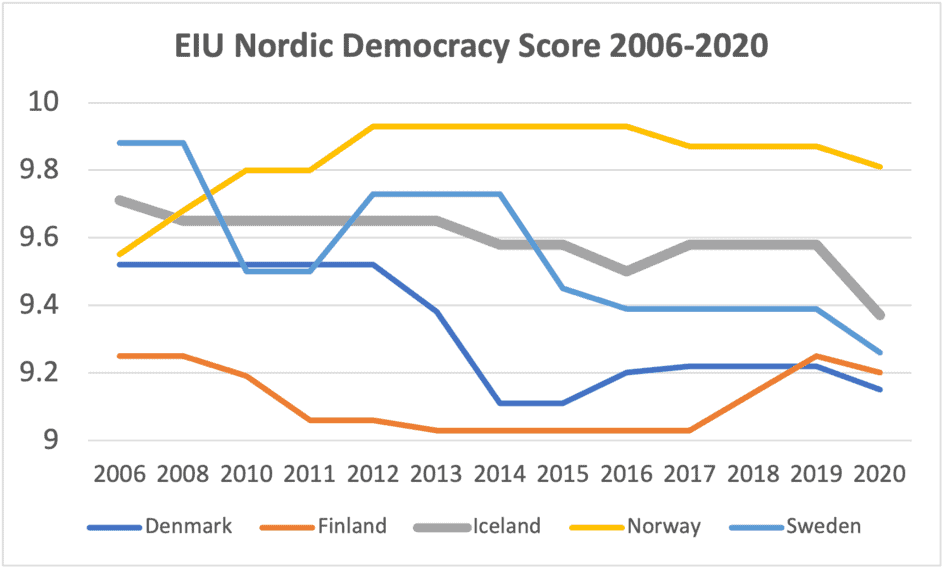

Once again, the Economist Intelligence Unit has missed the mark by assigning Iceland a democracy score second only to that of Norway in a group of 167 countries (see chart). True, Iceland’s score dropped sharply from 2019 to 2020, yet without demoting the island from its second-place finish among the Nordics, as well as across the globe (only New Zealand and Canada joining the Scandinavians in the top seven).

This score is too high—for at least two reasons.

First, the EIU awards Iceland a top score of 10 for ‘electoral progress and pluralism’. Yet votes in rural areas carry up to twice as much weight as urban votes—creating a provincial bias in parliament which has, since 1849, been the source of one of Iceland´s greatest political controversies. This bias has led foreign election observers, including from the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe, repeatedly to declare the voting inequality to be on such a scale as to constitute a violation of human rights.

Secondly, and even more importantly, the EIU report grants Iceland another top score of 10, for ‘political culture’. This without recognising that, temporarily humbled by the 2008 financial crash caused by reckless bankers and politicians, the Icelandic parliament resolved unanimously in 2010 that ‘criticism of Iceland’s political culture must be taken seriously’, stressing ‘the need for lessons to be learned from it’.

Thirty bankers and six others, mostly small fry, were sentenced to a total of 88 years in prison for crimes related to the crash. All the same, Iceland´s political culture remains essentially unchanged.

Getting Iceland right

Unlike the EIU, Freedom House and Transparency International get Iceland right. Freedom House lowered Iceland´s democracy score from 100 in 2014 to 94 in 2020, citing the influence of business interests over politics, corruption and a lack of transparency and media independence. Transparency International meanwhile lowered Iceland´s Corruption Perceptions Index from 97 in 2005 to 75 in 2020, suggesting a significant, gradual deterioration.

Most recently, in January 2021, Transparency International reported:

Iceland … and its reputation as a corruption-free country took a nosedive as revelations came to light that incriminated the country´s governing elite and its national companies. For example, the 2008 financial crisis exposed shady banks, the Panama Papers implicated the country’s former Prime Minister, and the Fishrot files revealed how far the country’s biggest fishery would go to extend its business and launder suspicious proceeds. Iceland’s foreign bribery problem is also a big issue. Last month, the OECD published a new report harshly criticizing the country´s enforcement efforts.

Harsh as this may indeed sound, Transparency International’s description does little more than scratch the surface of the serious issues involved. Along with some 600 other Icelanders, Iceland´s current finance minister was also exposed in the Panama Papers in 2016 (as was the minister of justice, since deceased), a clear sign of the island’s flawed political culture.

Accused of accepting bribes from Iceland as well as of corruption and abuse of power, two Namibian cabinet ministers and four others have been held in police custody in Namibia for more than a year, awaiting a court verdict next month. Three managers of Iceland’s largest fishing firm have been summoned to appear before the Supreme Court of Namibia in April to face accusations of bribery.

From late 2019 to late 2020, Iceland was placed by the Financial Action Task Force on its ‘grey list’ of countries deemed to have insufficient restraints on money laundering and the financing of terrorist organisations. Icelandic Supreme Court justices are engaged in petty court fights against one another. And a former member of parliament recently published a scathing best-seller on Berufsverbot in Iceland, exposing inter alia interference by vessel-owning oligarchs in academic appointments.

The people of Iceland are aware of all this. Gallup reported in 2012 that 67 per cent of its Icelandic respondents viewed corruption as being ‘widespread throughout the government’, compared with only 15 per cent and 14 per cent in Denmark and Sweden respectively. A 2018 survey by the Social Science Research Institute at the University of Iceland found that 65 per cent of respondents viewed many or nearly all Icelandic politicians as corrupt.

Beholden to oligarchs

The post-crash constitution, approved by 67 per cent of the voters in a 2012 referendum called by parliament, aims to stem corruption by strengthening civil-service and judicial appointments, among other things. The new constitution remains, however, to be ratified by parliament, still beholden to oligarchs.

They and their political clients object especially to the provision declaring that ‘Iceland’s natural resources which are not in private ownership are the common and perpetual property of the nation’ and that ‘government authorities may grant permits for the use or utilisation of resources or other limited public goods against full consideration and for a reasonable period of time’.

This provision, which was approved by 83 per cent of the voters in 2012, follows a 2007 binding opinion from the United Nations Human Rights Committee. This declared the discriminatory allocation of catch quotas in Iceland to constitute a violation of human rights and instructed Iceland to remove the violation from its system of fisheries management and to compensate the plaintiffs. The Icelandic government promised the UNHRC a new constitution, which would not discriminate in this way, but has failed to keep its word.

A further provision, stipulating equal weight of votes, won 67 per cent support in the referendum. The upcoming parliamentary elections, as with those in 2016 and 2017, will however still be held in breach of the express will of the people that all votes ‘shall have equal weight’.

Despite all this, Iceland´s long-term prospects seem bright—provided parliament musters the courage to confront the oligarchs and respect the will of the people, by ratifying the new constitution designed to reverse the retreat of Iceland´s age-old democracy. If not, Iceland risks becoming a failed state, a label which some sharp-eyed observers have attached to the United Kingdom and (under Donald Trump) the United States but which no reasonable observer would apply to Denmark, Finland, Norway or Sweden—not by a long shot.

This article also appears on VoxEU

Thorvaldur Gylfason is professor emeritus of economics at the University of Iceland and a former member of Iceland´s Constitutional Council.