At a European Parliament hearing earlier this month, the head of the European Central Bank acknowledged the role of rising corporate profits in fuelling inflation—according to Christine Lagarde, there may be a mismatch between supply and demand. In fact, large firms have become so dominant that they are able to increase their prices beyond the cost of production and yet not lose customers. Trade unions have long been denouncing such ‘greedflation’, driven largely by oligopolistic power and profit maximisation.

While lamenting the lack of relevant data, Lagarde called on competition authorities to look at the situation. But can, and will, they?

Technocratic exercise

A recent report with colleagues published by the European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC) reveals growing criticism of traditional competition tests in a context where corporate power is at an all-time high. Lagarde’s call will remain wishful thinking for as long as competition enforcement remains a technocratic exercise, isolated from the public interest and the impact on stakeholders.

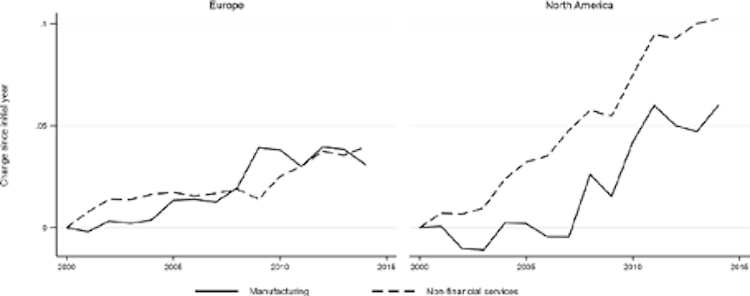

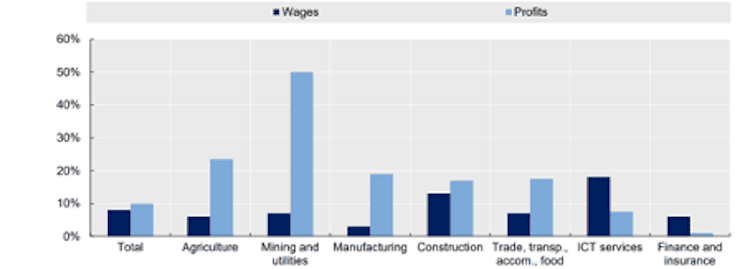

Corporate dominance can be inferred from the ability of a firm to charge excessive prices, well above the costs of production, without suffering competitively. Other indicators include the weight of the largest firms within an industry and the size of extraordinary profits (‘economic rents’). All three measurements (Figures 1 and 2) point towards corporate power increasing across all sectors, with multinational enterprises becoming fewer and larger.

Figure 1: concentration of manufacturing and services in Europe and north America

Figure 2: global increase in corporate power—markups and profitability indicators in 2019

In contrast with mounting corporate power, workers’ ability to bargain collectively for a higher share of value added is shrinking. Collective-bargaining coverage and trade-union density have been on the decline for more than a decade. Thus, there is an increasing asymmetry between corporate and labour power.

Lasting trend

In a labour market that is ‘fully competitive’, any attempt to pay a wage below market equilibrium would result in all workers leaving the firm immediately to take up a job elsewhere. Things are quite different in reality where the employer is unlikely to be confronted with a complete lack of available workers and so can set the wage somewhat lower while still retaining a certain volume of labour.

A labour market dominated by a few employers (‘labour-market monopsony’) has become a lasting trend throughout the countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development—particularly pronounced in the United States but also evidenced in the European Union. Such labour-market concentration has an exacerbating impact on the income distribution between labour and capital.

In recent years, profits have increased more rapidly than wages (Figure 3), in spite of serious economic disturbances which would normally occasion a drop in corporate profitability. This feeds into ever-widening income inequalities in our societies.

Figure 3: growth in nominal wages and corporate profits in the euro area, Q1 2019 to Q2 2022

‘Market power’

Yet competition authorities do not necessarily consider that there is a problem of dominance. ‘Corporate power’ connotes the concentration of capital ownership but such authorities prefer the usage ‘market power’. This a narrower notion, where relevant markets are defined from the subjective standpoint of consumers, almost exclusively in relation to specific products. A multinational enterprise can thus, objectively, be dominant overall because of its ability to increase markups and profits but be investigated by competition authorities only sporadically and in relation to particular goods or services.

In the EU, most mergers and acquisitions are cleared by the European Commission—often on condition that the participating companies implement targeted remedies to address competition concerns in neighbouring markets. Such a narrow perspective fails to capture the reality of today’s economic ecosystems: while the range of products and services in output markets can be diverse, multinational enterprises oversee the same business and labour strategy across their entire operations. Different markets controlled by the same corporation cannot reasonably be considered as if disconnected.

Yet the overall impact of concentrated corporate ownership is not assessed. Crucially for the labour movement, EU competition authorities invest no resources in measuring the concentration of labour markets and its consequences for wages and working conditions.

Sticking-plaster solution

Efficiency tests and considerations of impact on consumer choice may have led competition authorities to refrain from taming corporate power for fear they would kill the goose that lays the golden egg. Consumers are more than ever enjoying the choice offered by increased innovation and a very diverse range of products and services—we can watch thousands of series, at a time of our choosing and from the comfort of our own homes. But multinational enterprises are becoming bigger and bigger, so all our choices lead to the same few online platforms.

The commission regularly announces its intention to increase its scrutiny over unfair consumer practices, in particular in the digital sector. This is however a sticking-plaster solution, dealing with the consequences rather than the causes of mounting corporate power. A fundamental debate must be held on the objectives and tools of competition policies. Competition authorities must raise their game to capture the reality of economic power as a whole, rather than continue to focus narrowly on consumer interests.

Progressive forces from various constituencies are already putting in place co-ordinated strategies to bring visibility to the impact of corporate power, in the public interest. The ETUC report spotlights the impact on employment and the need to strengthen counterbalancing power within corporations through worker participation and social dialogue. It must also be possible to stop mergers when labour-market monopsony is around the corner.

Such interventions should pave the way towards a fundamental rethink of the goals of competition law. In the longer term, introducing a public-interest test would increase the capacity of competition authorities to capture economic power—having regard not just to individual products but broader sustainability goals and employment in particular.

Countries outside Europe—for instance, South Africa and the US—have introduced or are exploring public-interest tests as an aspect of competition policy. The EU should not continue to lag behind.