Further empowering the parliament and reducing unanimous decision-making would help tackle the EU’s democratic deficit.

Scholars disagree over the effect that territorial weights have on the democratic quality of a political system. Some argue that fully democratic legislatures need to vote simply by ideological majorities in most policy domains—those that affect all citizens as individuals rather than territories and/or do not generate permanent minorities. Others argue that for large, decentralised political systems territorial vetoes are always required and they do not see a plausible link between embedding territoriality in legislative institutions and democratic deficits.

In a recent study, I have looked at whether territorial vetoes in decision-making make it difficult for a political system to deliver the policies citizens want by looking at the case of the European Union. The EU is a heavily territorial system, often challenged on democratic-deficit grounds, which is undergoing constitutional reflection, as the Conference on the Future of Europe process attests. Examining the EU is particularly salient, since many policy challenges are, in our globalised world, supranational in nature and since the EU is taken as a model by many other global-governance institutions.

Co-decision reform

Some important policy issues are still exclusively decided by the Council of the EU (with one minister from the executive branch of each member state) via unanimity. The European Parliament has though been progressively empowered, most notably through the co-decision reform, which gives it the same veto powers as the council, effectively making it a co-legislator. That reform has, however, been applied in stages: different policy areas were assigned co-decision in different treaty reform rounds and often only subsets of the policy area were assigned.

I explored this ‘staggered’ application of co-decision—a reform which weakened the weight of member states in EU law-making—by looking at the case of EU employment and social policy. Here, co-decision was only applied in 1999 with the Amsterdam treaty and only to a subset of policies—those that were assigned the co-operation procedure before 1999. While the co-operation procedure granted slightly more powers to the European Parliament, its role was still largely consultative and the territorial chamber (the council) retained its near-absolute veto power.

I thus compared EU employment and social policies decided under the most territorial procedure (consultation) with those decided by co-operation before 1999 and by co-decision afterwards. This setup allows for a ‘difference-in-differences’ causal analysis and means we can control for time-varying characteristics which might affect EU policy and public opinion, such as the role of economic downturns, as well as characteristics specific to each sub-domain of EU employment policy (for example, the salience of policy proposals).

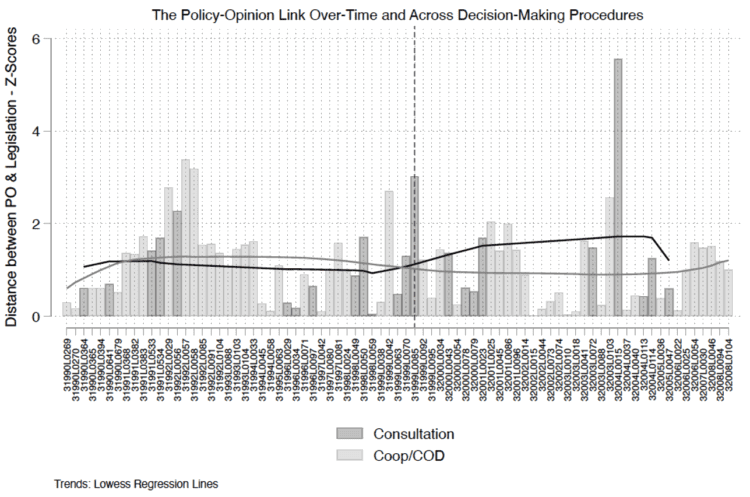

The texts of EU employment and social policies were analysed by samples of online human coders and were placed on the pro-worker or pro-business side on the basis of a thoroughly piloted and validated text-analysis codebook. Each EU policy was then matched to European public-opinion positions on the economic left-right scale (using Eurobarometer data as well as data from Devin Caughey, Tom O’Grady and Christopher Warshaw). The main outcome measured was the standardised difference between EU policies and European public opinion.

Better tracked

I found that EU policies decided by co-decision more closely tracked shifts in public preferences than those decided using other decision rules. The chart shows the main results of the analysis by plotting the policy-opinion standardised distances over time and by policy sub-topic/group. Post-1999 legislation decided by consultation (the most territorial procedure) was farther from public opinion than legislation adopted under co-decision.

EU legislation in employment policy tended to deviate further from the public mood after 1999. Had co-decision not been introduced, we would therefore have seen an overall increase in policy-opinion mismatches in this policy area post-1999 (the complicating effect of enlargement on the council-led aggregation of European public opinion might be a reason for this post-1999 trend). Legislation decided by co-decision appears to have tracked better the public mood than that decided by co-operation.

Absolute policy-opinion difference by treatment group

There are signs, therefore, that co-decision—a reform which fundamentally changed how EU laws are passed by increasing the powers of the European Parliament and majoritarianism in the council—has indeed improved the democratic credentials and the democratic legitimacy of EU policies (measured as the policy-opinion link).

This has significant implications for international organisations and it speaks to some important EU-reform proposals which animated the Conference on the Future of Europe. The backlash against globalisation is, according to some, partly due to international organisations having a democratic deficit. If international organisations are serious about tackling their democratic deficits as they acquire salient, redistributive policy competences, moving away from territorial, inter-state bargaining should be prioritised.

These findings lend credence furthermore to the expectation from democratic theory that strongly territorially-weighted decision-making rules can hurt the democratic legitimacy of policy outputs. My study thus has implications for any political system that strongly relies on territorial representation: democratic discontent, in fact, is expected to be higher in such systems, since their policies are expected to track public-opinion preferences less well.

This article originally appeared on the EUROPP blog of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Miriam Sorace is an assistant professor in quantitative politics at the University of Kent and a visiting fellow in European politics at the European Institute of the London School of Economics and Political Science.