As with its Polish counterpart, the Hungarian national recovery and resilience plan has been held up by the European Commission due to sustained rule-of-law concerns. Meanwhile, a series of articles on the effectiveness of past European Union funding in the country has been published in three parts by the Hungarian news portal g7.hu.

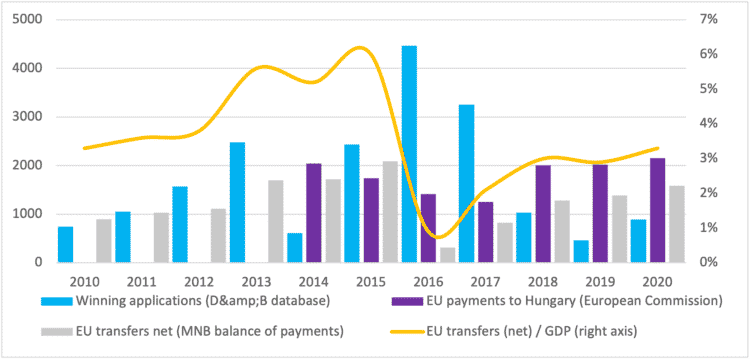

Since joining the EU in 2004, the Hungarian economy has received immense amounts of cohesion funding (Figure 1). From 2014 to 2020 alone, according to the Hungarian National Bank’s balance-of-payments data, Budapest received HUF9,200 billion (€24.6 billion) more in subsidies from Brussels than it paid into the EU budget. In these 11 years the equivalent of 3.3 per cent of Hungary’s gross domestic product flowed into the economy each year.

This support has provided a very significant boost, with nominal GDP growing by an average of 5.7 per cent annually over the same period. EU support therefore accounts for some 58 per cent of growth. In fact, with inflation taken into account, average annual growth was only 2.3 per cent. This means that without EU support, economic output could easily have declined, although this would require further analysis.

Actual EU subsidies flowing into the economy have however been much larger than the net position: projects approved between 2010 and 2020 amounted to HUF13,160 billion. This is a staggeringly high figure. It means the equivalent of 4.7 per cent of GDP was spent on EU-financed projects during the period.

Figure 1: total volume of EU subsidies (billion HUF) and their share of GDP (%)

The data for EU financing are however not transparent. They can be accessed via a Hungarian government website, but only if one searches for specific projects—export of bulk data is rendered impossible.

Corporate subsidies

Most of the EU funding has gone to government agencies and companies. Excluding those state firms which have received funds above HUF10 billion in the analysed period, we are left with the funds awarded to the corporate sector. Direct subsidies to corporations were HUF3,400 billion out of a total of HUF10,000 billion.

Based on data from the Hungarian Central Statistical Office (KSH), over the 11 years these subsidies to companies amounted to 1.1 per cent of their turnover, including state-owned companies. It means they received twice as much EU support as the corporation tax they paid in the same decade.

This amounts to a massive redistribution: the state is transferring vast sums to market actors. Even if we exclude subsidies above HUF20 billion—which presumably all went to state-owned companies—in 2010-20 firms subsidised by EU funds received HUF3,390 billion in subsidies, while paying only HUF2,086 billion in corporate taxes if we consider only private companies. But most of the massive HUF6,212 billion EU funding for state-owned companies was passed on to the corporate sector as funding or as public procurement.

Efficiency concerns

There are two important concerns about the efficiency of public funding for corporations: deadweight and substitution effects. In the former case, some or all of the investment would have been carried out anyway, so EU money replaces bank financing or equity. In the latter, due to demand constraints the enterprise supported only grows at the expense of non-supported businesses, even though these may be more efficient.

Concerns about the effectiveness of these subsidies are exacerbated by the fact that over the period analysed in 1,085 cases they were paid to firms which did not have any employees. Of these, 320 companies (receiving a total of HUF26.6 billion) had no turnover either!

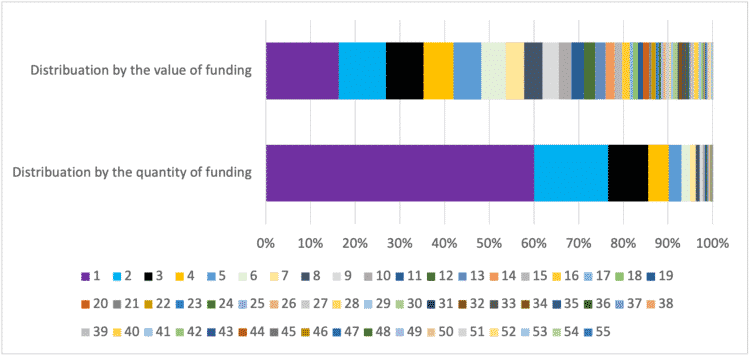

Sixty per cent of firms received only one grant, yet these comprised only 16 per cent of the total amount of aid (Figure 2). More than half was awarded to those which were beneficiaries at least five times—more than a third went to those with ten or more funded projects. While single grantees received an average of HUF40 million, those for which five to nine projects were supported received an average of HUF76 million.

Figure 2: distribution of EU funding by sum and number of grants won

Subsidy hunting

Overall, the growth rate of assisted firms was on average 20 per cent lower: all firms grew by 7.1 per cent on average during the period, while assisted firms grew by only 5.7 per cent. Far too many Hungarian companies base their business model on subsidy hunting, rather than real, commercially-sound activity.

It might still be argued that the companies supported would otherwise have lost workers or even have gone out of business. This is possible, of course, but sustaining poorly-performing firms is hardly a strategy for economic renewal.

The full study on which this article is based has been published by the think-tank Policy Solution