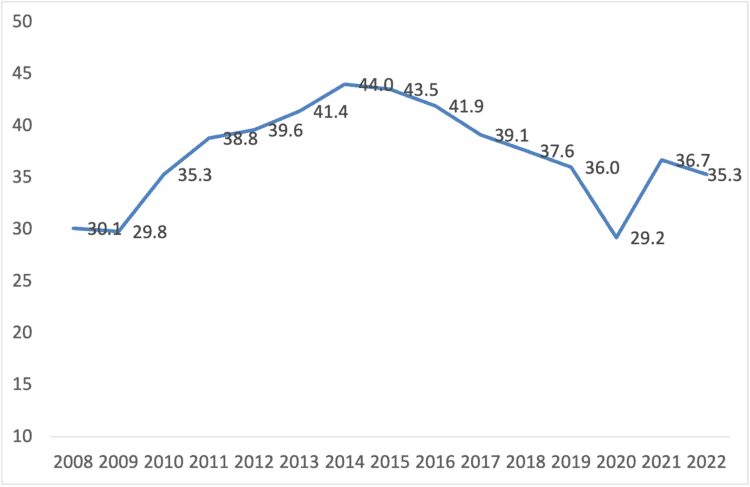

After the financial crash of 2008, the proportion of the unemployed out of work for a year or more rose continuously across today’s European Union member states, from around 30 per cent to 44 per cent in 2014. The ratio subsequently fell but returned to its pre-crisis level only in 2020—it had taken European labour markets over a decade to recover to an already high rate of long-term unemployment (see figure). Clearly, this represented a policy failure for the EU.

After the onset of the pandemic, long-term unemployment rose again. In the context of the cost-of-living crisis and higher rates of material deprivation, this calls for urgent political interventions in labour markets, to provide long-term unemployed individuals with decent work at decent pay.

Long-term unemployment (12 months or more) as a proportion (%) of total unemployment (EU27)

Long-term unemployment has far-reaching consequences, as the Austrian sociologist Marie Jahoda found in her groundbreaking research—her findings still valid today. The duration of unemployment steadily reduces the chances of re-employment, because of its negative impacts on psychological and physical health and skills and stigmatisation by employers. The wage penalty caused by former unemployment is well evidenced but it seems to be particularly harsh for the long-term unemployed. Long-term unemployment is also a problem from a democratic point of view, as it reduces political participation.

Promising instrument

An EU job guarantee could prove a promising instrument to eliminate long-term unemployment, achieve full employment, stabilise the economy and support the green transition. The idea is simple: the state offers a job opportunity at a minimum wage to everyone who is looking for work but unable to find a job in the private labour market. Participation in the programme would be voluntary.

These public jobs should be characterised by fair working conditions, permanent contracts and incomes, in line with the prevailing conditions in the respective countries, with wages set by minimum-wage laws or collective-bargaining agreements. This is to ensure public job creation is in line with the right to decent work.

The focus could initially fall on the most disadvantaged and vulnerable, providing social protection, preventing social exclusion and strengthening European social values as well as democratic participation. Democratic decision-making in the process of selecting which jobs should be created would be crucial to guarantee an adequate supply of socially useful work.

Job creation should be anchored in social dialogue with the social partners and the participation of other regional actors, to ensure that the programme responds to the unmet needs of the area. A European job guarantee would thus not only increase political partipation by avoiding long-term unemployment—it would also increase public acceptance of the EU by financing the production of public goods and services needed on the ground.

Targeting the most vulnerable would complement universal labour-market policies and offer solutions for those struggling the most to find a job. One way to measure the success of labour-market policies is in their capacity to re-employ the unemployed. As fast re-employment is understood as success, such policies however often have a selection bias towards those with the highest chances of reemployment. This ‘cream skimming’ might be one reason for the consistently high rate of long-term unemployment among those perceived as having less chance of re-employment.

Project design

Promising projects in France, Belgium and Austria show what successful project design might look like. In 2016, the French parliament passed a law to finance and implement Territoires zéro chômeur de longue durée, (TZCLD, zero long-term unemployment zones). The programme, in its second phase, has expanded to 60 municipalities, employing around 2,700 participants. TZCLD, while receiving national funding, are implemented locally through steering committees comprising all relevant stakeholders, targeting the long-term unemployed in the municipality.

The Walloon region in Belgium has started a similar pilot, aiming to create employment opportunities for 750 people out of work for more than two years across 17 projects. Half of the budget of €104 million for 2022-2026 for the TZCLD in Belgium comes from the European Social Fund.

Austria has a long tradition of public job-creation programmes, starting with Aktion 8,000 in the 1980s, Aktion 20,000 in 2017-19 and now the world’s first job-guarantee experiment with Modellprojekt Arbeitsplatzgarantie Marienthal (MAGMA) between 2020 and 2024. MAGMA offers guaranteed employment to those who have been unemployed for more than one year and has nearly eliminated long-term unemployment in the municipaliy of Gramatneusiedl. Evaluations by economists from the University of Oxford and sociologists from the University of Vienna found positive effects on participants’ non-economic as well as economic wellbeing.

Such initiatives combine active labour-market policies and use of local networks. By granting the right to decent work and guaranteeing to create jobs if necessary, they offer solutions for those who would otherwise be left behind. The experiences might serve as a blueprint for further job-guarantee programmes.

Fiscally neutral

Despite the objective success of these initiatives, they are vulnerable to ideologically motivated decisions to shut them down. To support them, the EU could expand its financing capacities and support a job guarantee under the European Pillar of Social Rights.

The fiscal cost of a European job guarantee would be neutral in the long run. The gross costs have been estimated at 1.5 per cent of gross domestic product. But a job guarantee would reduce public spending on unemployment per se, lead to higher tax returns and social contributions and increase aggregate demand. Long-term unemployment comes with enormous costs to society as well as the individual.

During the pandemic, the EU demonstrated its capability to prevent a major economic and labour-market crisis. The Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency (SURE) programme provided financial support for short-time work schemes all over Europe. Such a mechanism could serve as a role model for a new initiative to finance job-guarantee programmes.

NextGenerationEU showed how the EU could mobilise the fiscal capacity to provide funding for the recovery. And a lesson from the European Youth Guarantee has been that a job guarantee would have to be financed principally from the EU budget, on a basis of solidarity, with member states contributing according to financial capacity.

Expenditures on job-guarantee programmes should be excluded from the revised fiscal rules. Alternatively, member states could issue securities on financial markets to finance their programmes. The European Central Bank could re-establish, this time on a permanent footing, the temporary public-sector purchase programmes needed to provide support for those securities, as during the eurozone and Covid-19 crises.

The time for a European job guarantee is now—it is only a question of political will.

This is part of our series on a progressive ‘manifesto’ for the European Parliament elections