Given the substantial increase in public debt due to the pandemic, there is a growing debate on new rules or standards for fiscal policy in the euro area. It is obvious that the reference value of 60 per cent of gross domestic product inscribed in the Maastricht treaty of 1992 can no longer serve as an anchor for the fiscal-policy framework.

The target was derived from the average debt/GDP ratio of European Union member states in 1990. It thus lacks the sound theoretical and empirical basis required of any evidence-based policy. And with an average debt among the advanced economies in 2021 of 122 per cent—even 140 per cent for the G7—the 60 per cent benchmark is now completely detached from reality.

Debt-brake straitjacket

The need to reform the fiscal rules should be taken as a chance fundamentally to rewrite the whole macroeconomic rulebook. It was designed in the 1990s in the shadow of the inflationary experiences of the 70s and 80s. It therefore aimed mainly to prevent short-sighted governments from spending excessively and accumulating unsustainable debt.

In addition to the 1997 Stability and Growth Pact, Germany adopted the Schuldenbremse (‘debt brake’) in its constitution and persuaded other EU members to implement a similar straitjacket with the fiscal compact of 2013. Central-bank independence, but with a clear mandate for price stability, was a key institutional arrangement, ensuring irresponsible politicians faced a mighty inflation watchdog.

The asymmetry of this rulebook became evident in the 2010s, a period with a deflationary bias and not only in the euro area. Already in 2013, the former United States Treasury secretary Larry Summers identified the problem of ‘secular stagnation’, which he attributed to ‘excess savings’—an excess of aggregate supply over demand. Unfortunately, politicians at the time overlooked Summer’s call for expansionary fiscal policies.

This left monetary policy as the only instrument, as central banks tried to stimulate aggregate demand with very low and even negative interest rates. But this could provide only limited relief from deflationary pressures and low interest rates made it difficult for many households to save.

Symmetrical rules

The time is therefore ripe for a symmetric macroeconomic rulebook. The first commandment of fiscal policy can be found in Abba Lerner’s theory of ‘functional finance’:

The first financial responsibility of the government (since nobody else can undertake that responsibility) is to keep the total rate of spending in the country on goods and services neither greater nor less than that rate which at the current prices would buy all the goods that it is possible to produce. If total spending is allowed to go above this there will be inflation, and if it is allowed to go below this there will be unemployment.

An almost identical approach can be found in the 1967 Act to Promote Economic Stability and Growth in Germany. Section 1 reads:

In their economic and fiscal policy measures, the Federation and the states shall observe the requirements of overall economic equilibrium. These measures shall be taken in such a way that, within the framework of the market economy, they simultaneously contribute to price stability, to a high level of employment and external equilibrium, accompanied by steady and adequate economic growth.

Of course, the explicit responsibility of the government for the price level leads to an assignment problem, given the price-stability mandate of the central bank. How could this be solved?

A useful framework could be provided by the strategy of inflation targeting, which so far is only practised by central banks. In this strategy, medium-term inflation forecasts play a decisive role. When the inflation forecast exceeds the inflation target, a monetary tightening is required and vice versa. With an explicit responsibility assigned to fiscal policy for price stability, inflation forecasts could also provide guidance for the fiscal-policy stance.

This applies in particular to the concept of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). If the inflation forecast is below or at the inflation target, large countries can promote growth and employment without any financial constraint. If the inflation forecast is above the inflation target, the real resource constraint becomes evident and must be observed even in the world of MMT.

Deflationary bias

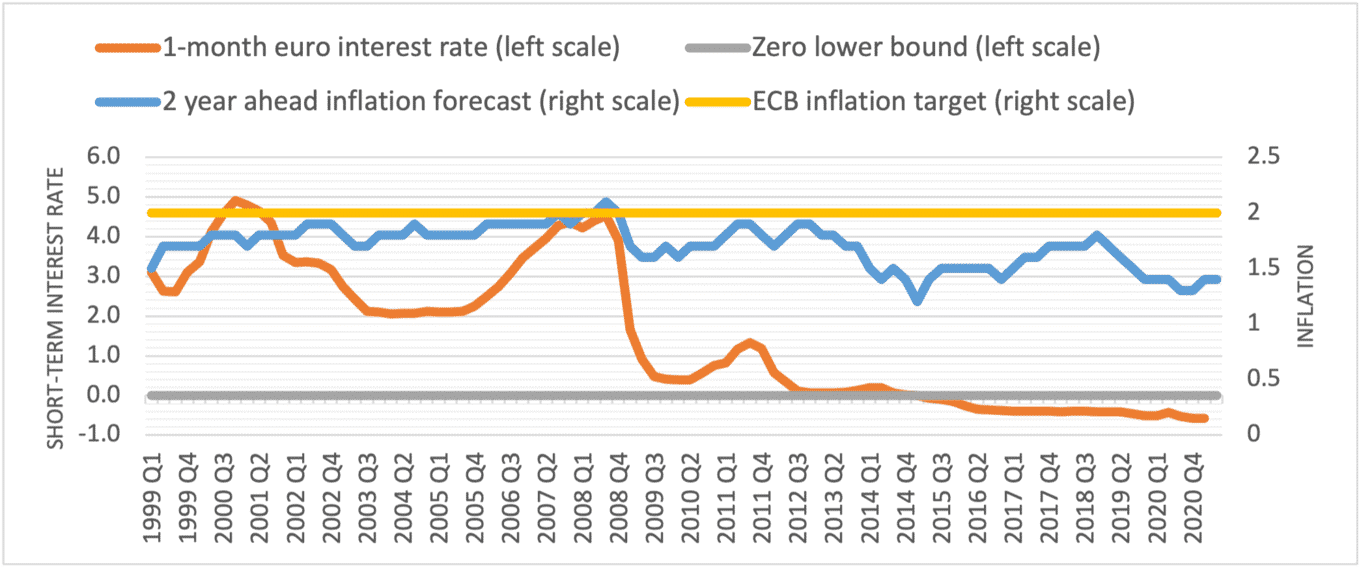

The experience of the eurozone in the 2010s provides an interesting example of this approach (chart 1). Since 2013, the inflation forecasts by the European Central Bank’s Survey of Professional Forecasters have indicated a deflationary bias in the euro area, undershooting the 2 per cent target. At the same time, the ECB’s policy rate has been close to the zero lower bound or even negative.

Chart 1: euro area inflation forecasts and interest rates

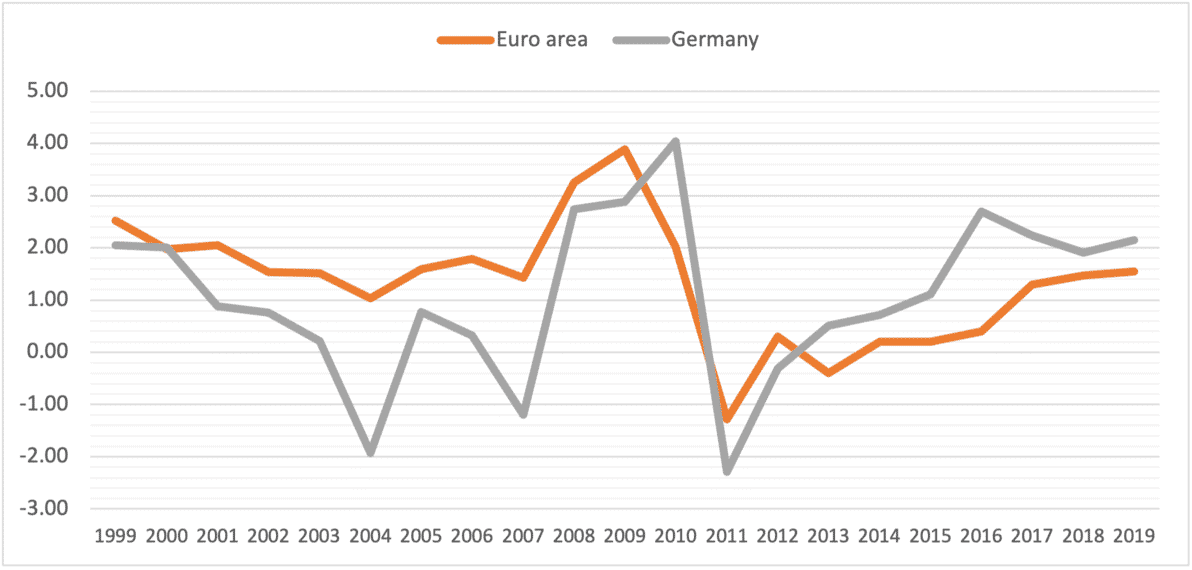

Had fiscal and monetary policy held joint responsibility for price stability, a fiscal stimulus would have been called for, to stabilise this situation. During this period, however, fiscal policy in the eurozone was one-dimensionally focused on deficit reduction, reflected in effective stagnation of government expenditure in real terms (chart 2). With a ratio of government expenditure to GDP of almost 50 per cent in the euro area, governments could have stabilised the economy but did not. Rather, they themselves provided a major obstacle to recovery.

This also applies to Germany, which in spite of its low government debt was unwilling to support the weak eurozone economy during a critical phase. It is an irony that the same German politicians who were unwilling to stimulate the euro area were at the same heavily complaining about the ECB’s low interest rate and its negative effects on the German saver.

Chart 2: year-on-year change in real government expenditures (%)

Thus, with a symmetric macroeconomic rulebook for monetary and fiscal policy, a much better fiscal performance of the euro area would have been possible. This even applies to the financial situation of governments. As the multipliers for expenditures arising from fiscal loosening are estimated to lie between 2.3 and 4 in the situation of the zero lower bound, additional debt-financed public spending would have boosted GDP and thereby contributed to a decline of the debt/GDP ratio.

Co-operative approach

What are the implications of a symmetric rulebook in a situation where inflation forecasts exceed the inflation target? With stubborn governments that do not care about inflation nothing would change. The central bank would increase interest rates to suffocate the inflationary tendencies, which mainly affect investment activity.

However, with a government aware of its responsibility for price stability, a co-operative approach would be possible. The government and the central bank could try to identify the causes of inflationary pressure and determine the best remedy. In addition to simply raising interest rates, other solutions would be possible. For instance, if inflation comes from a shortage of workers, the government could open the labour market for foreign workers. If inflation is caused by a boom on the housing market, the government could impose higher taxes on house purchases in addition to macroprudential measures.

Establishing an explicit national fiscal responsibility for inflation is especially useful in a monetary union. If a member country is affected by an idiosyncratic shock, the monetary policy of the ECB can only very partially compensate it, while higher or lower interest rates could have destabilising effects on other member states. Therefore, only national fiscal policy can provide adequate therapy.

Astonishingly, the Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure, introduced by the EU in 2011 to ‘identify, prevent and address the emergence of potentially harmful macroeconomic imbalances’, does not include inflation or inflation forecasts among numerous indicators. National inflation targets for the eurozone member states would require a corridor of 1-3 per cent, so that an average rate of around 2 per cent became possible.

A quarter of a century has passed since the first rulebook for the euro area was written. It is time to revise it fundamentally—transforming it into a symmetric framework, with fiscal and monetary policy jointly responsible for macroeconomic stabilisation without generating inflation or unemployment.

This article is a joint publication by Social Europe and IPS-Journal

Peter Bofinger is professor of economics at Würzburg University and a former member of the German Council of Economic Experts.