Amid all the talk of its imminent death, it is worth remembering that the European Green Deal was not meant to be. The EGD is, in fact, a resilient accident: it was on nobody’s platform during the 2019 European Parliament election campaign and it survived the pandemic, Russia’s imperialism and the inflation shock.

While anti-ecological populism is in full flow in many European Union countries and non-governmental organisations are right to be worried about environmental regressions, there are at least three reasons to believe the EGD is here to stay: path dependency, EU values and Europeans’ aspirations. First, the EGD is now the law of the land, enshrined in dozens of legislative provisions protected by EU regulations—it will not easily be dismantled. Secondly, it follows directly from the EU’s commitment to sustainability, which is at least 30 years old and has never been so relevant at a time when the biosphere is suffering and collapsing in places. Thirdly, albeit imperfectly, it speaks to EU citizens, who now consistently put environmental concerns at the top of their agenda. It is thus time not to lament the deal but to consolidate it.

Tracking progress

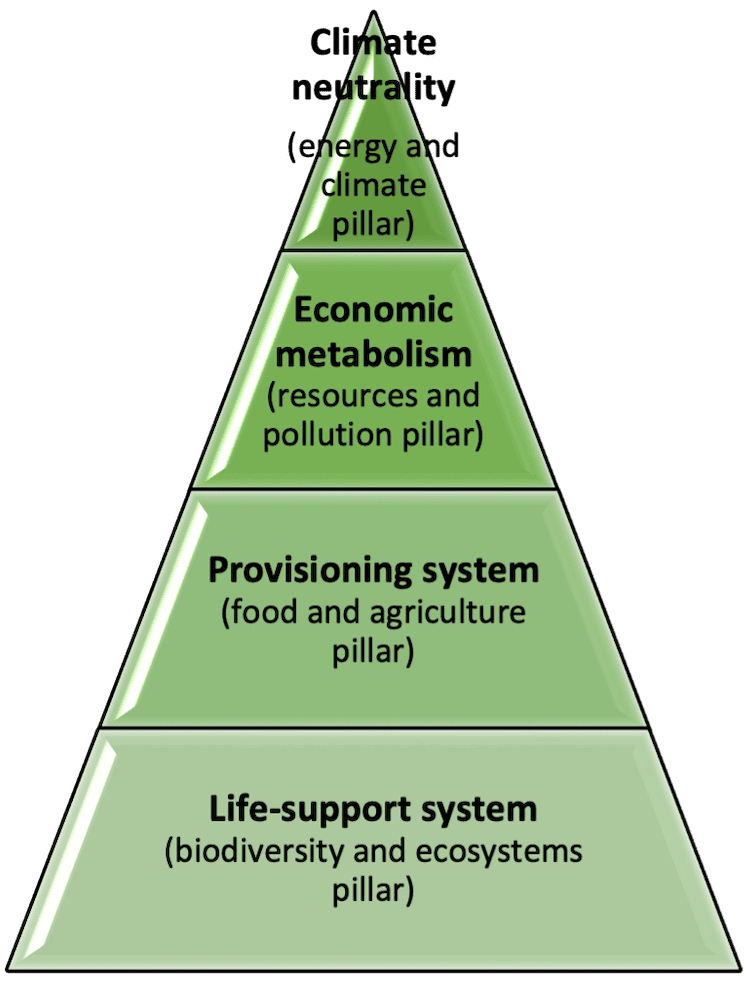

A first avenue to pursue is to take the EGD as it is and attempt to track its progress and identify its shortfalls. Jérôme Creel, Emma Laveissière and I have created a new analytical framework and statistical tool, which allows us in part to do that—the Green Deal Compass. Consisting of the metrics that feature in European legislation, it offers a representation of the EGD in the form of four pillars: climate neutrality (climate and energy), economic metabolism (resources and pollution), the provisioning system (agriculture and food) and the life-support system (biodiversity and ecosystems). These pillars can be logically ordered into a pyramid (Figure 1).

Figure 1: the Green Deal at a glance

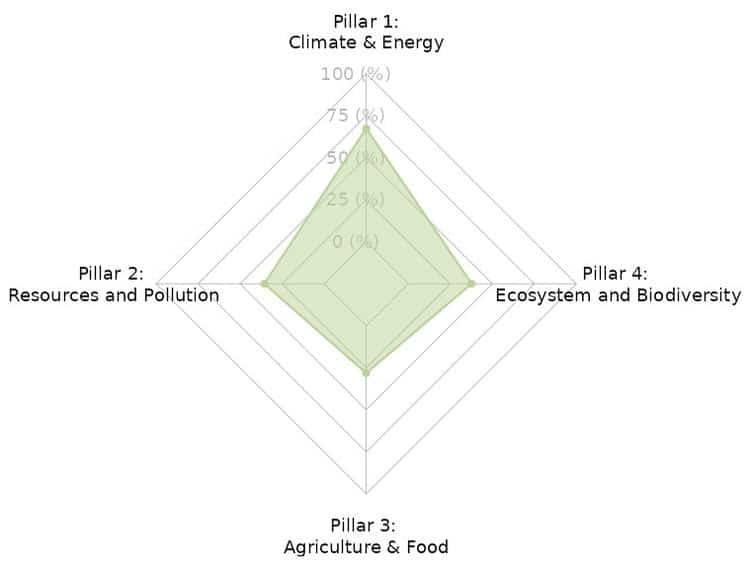

To track tangible progress towards the EU’s 2030 legal goals, we use distance-to-target methodology with real-time Eurostat data. Collating 13 existing metrics, we have created a synthetic indicator—the Green Deal Radar (Figure 2).

Figure 2: the Green Deal Radar

This shows that the EGD is achieving its objectives, albeit in an unbalanced way which eventually may jeopardise its still-fragile success: the base of the pyramid represented in Figure 1 is too narrow to sustain the top, climate neutrality. There are obviously other imbalances that cannot be measured using this tool, starting with the lack of social ambition in the Green Deal as it stands today.

Coherent policies

In another study, with Julia Steinberger, Yamina Saheb and François Denuit, we thus offer ‘A Blueprint for a European Social and Green Deal’. In our view, the EU needs a genuine European path toward a Green Deal better aligned with core European values and Europeans’ twin aspirations of social justice and environmental responsibility. It also needs coherent social-ecological policies, instead of allowing vital social and environmental goals to be pitted against one another or attempting to offset ill-designed environmental policies with social fixes.

This is not because of any bureaucratic imperative falling from the sky but because, in their daily lives, Europeans are facing a social-ecological predicament which, contrary to the rhetoric of anti-ecological populism, stems from the cost of non-transition: social inequalities have been exacerbated by the failure to effect the green transition of energy and food systems over past decades; these translate into massive energy and mobility poverty, food and housing insecurity and health vulnerability.

The ‘Blueprint for a Social and Green Deal’ we offer is indeed grounded in the lives of Europeans and imagines new kinds of public policies and practical reforms. This push forward is not just eminently possible but is urgently needed and should be precisely outlined. In our view, this entails upgrading the EGD policy pillars using the European Pillar of Social Rights as the cornerstone, reimagining the governance of the European social-ecological compact and financing the two-pronged eco-social advance.

One of the key challenges is to articulate social policies which are largely national with environmental policies which are largely European. Another is to put trade unions at the centre of a new EU effort towards just transition—not just for EU citizens but with them. (This is why we propose to institute a permanent European citizens’ assembly to deliberate and make proposals on social-ecological issues on a regular basis, starting with energy and food).

Comparative advantage

Ecological crises are accelerating before our eyes but they cannot be addressed, let alone mitigated, by ignoring social emergencies. Contrary to mainstream economic views, the EU is well equipped to face this complex challenge and it can do much better than imitate the United States’ faltering ecological industrial strategy.

EU member states enjoy the global comparative advantage of having developed strong social policies as well as mutualised, robust environmental policies. This unique combination is not a burden holding back ‘competitiveness’ or ‘growth’—it is one of the EU’s most valuable and yet unsung assets in today’s shock-prone world. It is the true definition of the European model: the social-ecological way of life is one of the most integral, robust and peaceful definitions of European identity.