Amid much rhetoric of a green recovery, only about a quarter of associated spending in Europe fits the bill—despite the benefits.

A year ago, the arrival of Covid-19 thrust Europe into its worst economic crisis since World War II. If the official rhetoric to ‘build back better’ is to be taken seriously, policy-makers must better prioritise green recovery investment and rebut an economic system coupling growth with greenhouse-gas emissions.

The economic, climate and social benefits of green public spending could drive future prosperity for the European continent, in the short and long term. A growing body of evidence suggests green public investment can deliver economic returns equivalent to, or even greater than, conventional stimulus.

A May 2020 paper surveyed leading economists to identify policies with high potential to secure economic and climate impacts following the panic. Clean physical infrastructure, building-efficiency retrofits, investment in education and training, ‘natural capital’ investment and clean research and development found favour. Another study published last year, commissioned by the UK Energy Research Centre, found that amid recession renewable energy investment could generate more jobs than ‘dirty’ investment and lead to more cost-efficient electricity supply.

In the long term, global economic prosperity will be driven by emerging green industries, including green energy, green transport and green industrial services. Countries investing to build green competitive advantage could reap the benefits, in jobs and growth, for decades to come.

Green public spending can also improve social mobility. For individuals it means equipping new workers with future-proof skills. For communities it could mean supporting rural areas with sustainable electrification and domestic energy-efficiency investments. The spin-offs in health and social wellbeing could be enormous and enhanced with targeted policy design.

Potential impacts

The Global Recovery Observatory tracks pandemic-related public spending by the 50 leading world economies and assesses potential impacts on the environment, society and economy. The initiative, led by the Oxford University Economic Recovery Project and supported by the United Nations Environment and Development Programmes, the International Monetary Fund and the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit, however finds that only 18 per cent of global recovery spending, and 2 per cent of total spending, has been green.

While Europe has been the greatest contributor to global green spending—€208 billion excluding European Commission programmes—this reflects only a minor portion of total spending. Only 26.5 per cent of recovery spending, and 4.3 per cent of total announced spending in the European Union and the United Kingdom, is expected to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions or air pollution, or strengthen natural capital.

Within Europe, the characteristics of national spending have varied significantly across countries. In 2020, France led the way in total green spending (€57 billion), with Germany (€47 billion) and the UK (€43 billion) close behind.

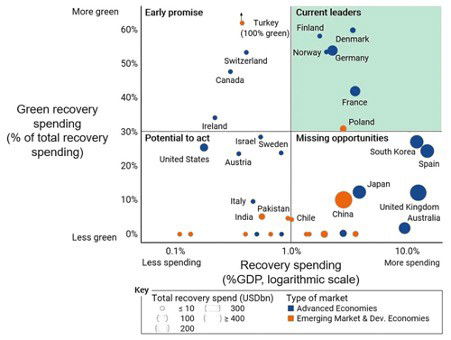

Considering only recovery spending oriented to the long term and comparing this with total recovery expenditure and gross domestic product (Figure 1), Denmark, Finland, Germany, France, Norway and perhaps even Poland emerge as global leaders. Other European countries, such as the UK, lag behind and many are yet to announce significant recovery spending packages.

Figure 1: green spending as proportion of recovery spending and the latter as proportion of GDP

One highlight of 2020 was France’s September stimulus package. This reserved funds for several green initiatives and allocated more than €7 billion to energy-efficiency retrofits. The programme funds insulation, heating, ventilation and energy-audit work, covering households, social housing, public buildings and small and medium enterprises. Available evidence suggests that ‘shovel-ready’ clean-energy retrofits can capture economic and social benefits by delivering timely fiscal stimulus and lowering energy costs for individuals in public housing, often left out of programmes aimed at homeowners.

As another highlight, last June Germany announced its National Hydrogen Strategy, with €7 billion for domestic investments in hydrogen production and applications, as well as €2 billion for a new international hydrogen trade network. The investment comes as the economics of hydrogen for transport and industrial applications begins to improve, with cheaper renewables, more efficient electrolysis technology and global investment continually driving down hydrogen production costs.

Many ‘dirty’ and ‘environmentally neutral’ fiscal stimuli could have been made more economically effective and environmentally sustainable. For instance, several billions spent on bailouts for airlines could have included green conditions, mandating airlines to develop and meet pathways for carbon reduction. A positive example is a French liquidity provision for Air France, which requires a halving of carbon-dioxide emissions per passenger-kilometre by 2030, compared with 2005 levels.

Several otherwise promising green policies have fallen short, failing to prioritise a longer planning horizon. Last July, the UK’s €3.5 billion ‘green homes grant’ was announced, incentivising homeowners to invest in low-carbon heating, insulation and efficient windows and doors. Delayed introduction likely led to reduced demand in July to September and the short initial window led to excess demand above contractor capacity. Without recent attempts to address these issues, the programme risked an outcome that merely shifted short-term demand, with minimal net impact on greenhouse-gas emissions and a diminished role in creating jobs and stimulating the domestic economy.

Next Generation EU

The European Commission is attempting to use the €750 billion Next Generation EU package to unlock a path toward green transition for many countries currently lagging. Under the scheme, member states have until April 30th to finalise plans to allocate at least 37 per cent of funding to ‘green’ measures approved by the commission.

The true greenness of what is and is not to be accepted however remains dubious. Additionally, as demonstrated in Germany’s draft plans, there is a risk that countries simply direct new funds to already promised projects.

To maximise net economic impact, it will be important for Next Generation EU funds to be disbursed swiftly, as speed plays a key role in maximising the economic effectiveness of public spending. Additionally, by acting early, EU members could get ahead of major recovery expenditure in the United States, which will have to get through the Senate.

Finally, European recovery spending ought to link into a competitive industrial policy, which positions member states to win in the long term. Beyond the recovery, policy-makers should consider green-procurement standards to incentivise clean manufacturing, invest in green research and development, and develop sustainable trade agreements and export standards.

Extreme disparity

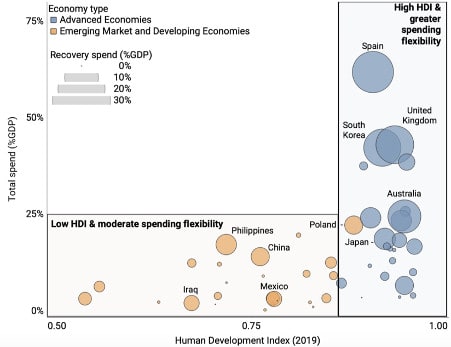

The extreme disparity between public investment in advanced and emerging or developing economies also demands recognition. Greater debt burdens, higher interest rates and drastically reduced taxation inflows have constrained the ability of many already struggling states to invest in their economies.

In the absence of generous international support, this is already driving a decade of lost progress in combating poverty and a widened gap between the global north and the global south. Europe must urgently look beyond its borders to provide developing countries with generous, long-term assistance through concessionary finance and grants.

Figure 2: recovery spending as a proportion of GDP and vis-à-vis the Human Development Index

Greenhouse-gas emissions have already begun to rebound in Europe. Without co-ordinated intervention, the continent will return to an ‘old normal’, where growth is linked to emissions and the climate emergency looms larger every year. Yet the tools to avoid such a reversion not only bring valuable economic and social benefits but also are tried and tested. What are we waiting for?

Brian O’Callaghan is lead researcher and project manager of the Oxford University Economic Recovery Project. He is an Australian Rhodes scholar and consultant at the Robertson Foundation, covering topics in energy and the environment. David Tritsch is a research assistant for the Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment and a Philosophy, Politics and Economics student at the University of Oxford.