A friend recently gave a seminar on the destructive impact of income inequality, laying out how deeply it damages a vast array of health and wellbeing outcomes, and how it affects the affluent as well as the poor, only to be asked during the question period—with some acerbity—why he was ignoring the deep and damaging inequalities between men and women.

I’ve frequently been asked the same question, with varying flavours. Why am I not writing about racial and ethnic inequalities instead of inequalities of income? Why am I not talking about the elderly or those with disabilities? What about migrants? And what about inequalities between the global north and south or between neighbourhoods? What is so significant about income anyway—surely wealth matters more, or social class or power?

Fraught questions

These are fraught questions, imbued with the frustration and righteous anger of those who are at the sharp end of the deep inequalities permeating our societies. Over the last six months I’ve been chairing an Independent Inequalities Commission, set up to offer policy solutions to inequalities in the city-region of Greater Manchester in northern England.

I’ve been listening to the testimonies of affinity groups and communities of identity, whose activism for social justice can sometimes feel as if it is colliding with the collateral injustices experienced by other, different groups, as well as running up against the entrenched and intractable problems caused by socio-economic inequality. But this is not a zero-sum game.

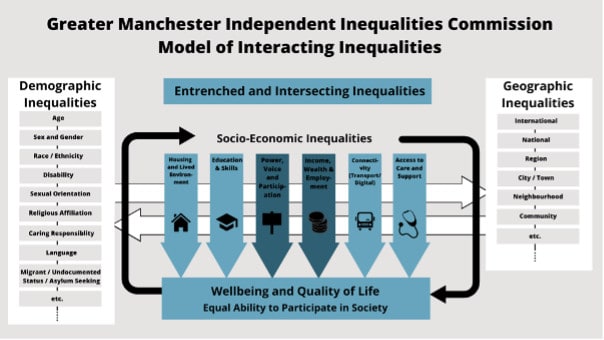

There are, of course, deep fissures between groups: inequalities between men and women, between ethnic groups, between those with disabilities and those without; inequalities related to sexual orientation, language, religion and migration status, and inequalities between places—between neighbourhoods or cities—indeed at all geographical scales. We can think of these as ‘horizontal inequalities’, inequalities between groups of people with different characteristics or who live in different places.

Then there are the pressures of what we can call the ‘vertical inequalities’: the inequalities of income and wealth, the disparities in access to resources and power. The scale of these vertical inequalities is a measure of the social hierarchy, which presses down on all the groups experiencing discrimination—exacerbating the horizontal inequalities.

Understanding connections

Instead of trying to prioritise different kinds of inequalities to be addressed, trying to understand the connections between them might help us tackle them.

On International Women’s Day, it is fitting to focus on how the inequalities experienced by women and girls—the fissures between their experiences and those of men and boys—are widened by the vertical inequalities pressing down through society, from the rich and powerful at the top to the poor and disempowered at the bottom.

In more economically unequal societies, women’s status is lower than in more equal ones. In other words, in societies with bigger differences between rich and poor, women are less enfranchised and have less power, resources and prestige than women in societies where those differences are smaller.

This is true of comparisons among nation-states, and among states and regions within countries. Women’s political participation (representation in national and state legislatures), their earnings relative to men and female rates of completion of higher education are, on average, worse in more unequal US states and in more unequal developed countries. Across the countries of Latin America (where an arguably coherent culture and commensurable data allow fair comparisons), intimate partner violence is higher where income inequality is greater.

Think of society as a social ladder. In more unequal societies, the ladder is propped at a steeper angle and the rungs are further apart. Where one stands on that ladder matters more in a more unequal society: status and hierarchy are more important, competition for status more intense. So inequality is linked to more aggression and more pugnacity, to more bullying and more violence, to stronger dominance hierarchies among men. And when there is more status competition among men, women’s status suffers more.

Red herring

It’s a red herring to argue that one kind of inequality matters more than another. We wouldn’t be happy if there was no gender pay gap but everyone had low pay. With larger material inequalities, the disadvantage of all groups who suffer lower incomes—women, ethnic minorities, the disabled—will be greater. We need to create virtuous circles and helpful precedents to reduce both horizontal and vertical inequalities.

A requirement for large companies to publish gender-pay ratios came into force in the United Kingdom in 2017. Simply reporting pay gaps doesn’t solve them, of course, and they pose statistical and confidentiality challenges, but it can help. As these reporting rules are quite recent (and implementation has been interrupted by the pandemic), we don’t have much by way of data. But there are some positive signs: between the first two rounds of reporting, half of businesses reduced the gap.

Shining the light on one kind of inequality can pave the way to looking at others. A requirement to report chief-executive pay, and the gap between that and the average worker—a vertical inequality—followed hard on the heels of reporting on gender pay gaps—a horizontal inequality—coming into force in the UK in 2019. There is great expectation that we shall soon see a requirement for larger companies to report ethnic pay gaps as well. A demand for one kind of equality can fuel demand for another.

Impressive example

Finally, here is one impressive example of how higher status for one group can improve everyone’s wellbeing: countries with female leaders have had lower Covid-19 deaths. Some of this is due to coronavirus-specific policy-making—women in leadership seem to have enacted policies which flattened the epidemic curves, of transmissions, infections and deaths, faster and more effectively than their male counterparts.

But just as likely is that electing a female leader reflects a society with a wider set of progressive values. I described earlier how smaller inequalities of income lead to increases in women’s political participation—women are in power because their societies are more equal, because male dominance hierarchies have been loosened and because more egalitarian societies value diversity and inclusion.

Structural misogyny, racism, able-ism and so on restrict the resources and opportunities of particular groups but the pressures of income inequality, social-class discrimination and rentier capitalism weigh down on us all. That’s why I’ve tended to focus on the vertical inequalities. But let’s make common cause, and use the interconnections between vertical and horizontal inequalities to find points of leverage where we can challenge the whole system.

This article is a joint publication by Social Europe and IPS-Journal