During 2019 and 2020, 21 gay and lesbian couples in Romania joined a complaint against the state to the European Court of Human Rights over the lack of official recognition of their relationships. After over a decade of bottom-up activism and unsuccessful reforms, such couples continue to be legally invisible in the country.

Gays and lesbians in Romania cannot make medical decisions on behalf of their partners. They cannot take leave from work should their partner get sick or die. They cannot receive compensation if someone accidentally kills their partner or a survivor’s pension. In sum, they cannot enjoy most of the rights and benefits of heterosexual spouses.

In a major judgment delivered on Tuesday (Buhuceanu and Others v Romania), the European Court of Human Rights condemned the government in Bucharest for its failure to guarantee the rights of such couples. The court affirmed that under the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)—the key Council of Europe instrument it is mandated judicially to interpret—same-sex couples enjoyed a right to civil unions.

Non-intuitively, this stems from a privacy right: article 8 of the convention requires states-party to respect one’s private and family life. Yet even though article 8 protects a negative sphere where couples must enjoy their family ties, it also creates—in the language of the court—certain positive obligations, which require the state to give content to the right. Only a comprehensive framework can allow same-sex couples fully to enjoy their family relationship, which is hence required under the convention.

Radical disagreement

The court reached a similar conclusion against Russia in January (Fedotova and others v Russia), after the federation had already abandoned the convention, for failing to provide civil unions for same-sex couples. Russia’s controversial exit from the Council of Europe last year—departing before it was pushed—received little media coverage, coming as it did within days of the invasion of Ukraine. It marked a radical disagreement over the very conception of human rights which the (now) 46-member European organisation, established in 1949 in the shadow of the Holocaust, seeks to promote.

The Russian Foreign Ministry described the Council of Europe as a vehicle for western ‘narcissism’. In this perspective, the ‘west’ has monopolised the acquis of the court to promote a faux-universal conception of human rights, a contingent manifestation of an ‘ultraliberal ideology’. In similar terms, the head of the Russian Orthodox Church, Kirill I, claimed that a ‘minority’ was ‘imposing’ ‘homosexual’ marriage on a ‘repressed’ and therefore persecuted majority.

LGBT+ rights are then represented as tools aimed at overthrowing the most conservative societies. They appear an act of ‘ideological aggression’ by the west, rather than principled and pragmatic solutions to practical problems.

Far-reaching consequences

The decisions against Russia and Romania were barely predictable a few years ago. And they will have far-reaching consequences for the landscape of LGBT+ family rights in Europe. They will predictably exert pressure beyond Europe too, due to the court’s authoritative voice in the interpretation of human rights globally.

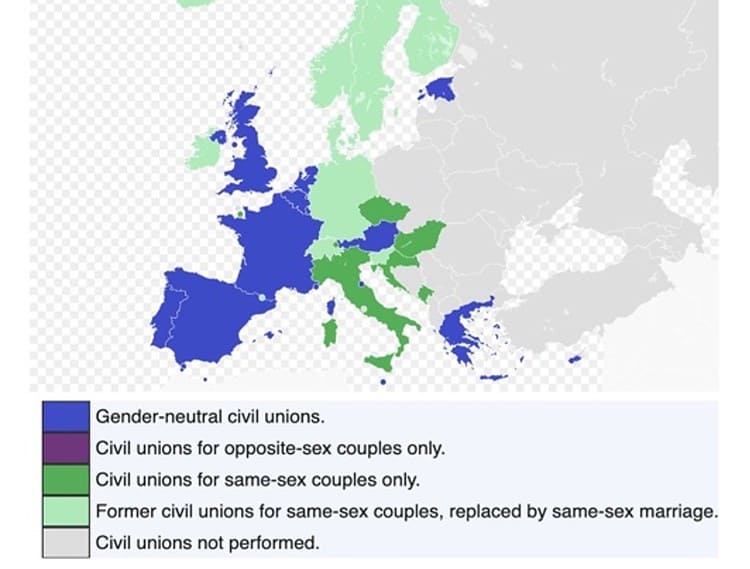

After these two judgments, same-sex couples in every corner of the system of the ECHR can sue their state if it refuses to legalise their unions. The framework of the convention reaches as far as the Caucasus, including states such as Georgia and Armenia. As the map below illustrates, several states are vulnerable to lawsuits and after this week’s decision there is little doubt as to how the court will rule. This is a remarkable advance, in a world where LGBT+ rights have suffered setbacks in Europe and beyond—as exemplified by the illiberal turn in central and eastern Europe and the enactment of criminal provisions against homosexual behaviour in states such as Uganda.

Slovakia and Poland only recognise unregistered cohabitation. With the decision against Romania expressly speaking for the first time of a right to ‘civil unions and registered partnerships’, such legal frameworks will be insufficient. According to the court (§78), ‘the applicants have a particular interest in obtaining the possibility of entering into a form of civil union or registered partnership in order to have their relationships legally recognised’.

Contracting parties lacking any mechanism for recognition include Albania, Azerbaijan, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Bulgaria, North Macedonia, Turkey, Georgia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Moldova, Serbia and Ukraine. Same-sex couples from these countries now have a powerful set of precedents to sue their state for failure to comply with the convention. As in all its judgments, the court recognises a ‘margin of appreciation’ as to how to fulfil convention obligations but defines this as ‘significantly reduced’ in this case, given the ‘clear ongoing trend towards legal recognition of same-sex couples’ and the ‘particularly important facets of the personal and social identity of persons of the same sex’ at stake (§74).

Death-knell sounded

The court’s decision in Oliari and others v Italy in 2015 compelled Italy to introduce civil unions. This was however a rather cautious decision which seemed to limit its applicability to Italy, due to special circumstances: Italy’s Supreme Court and Constitutional Court had repeatedly urged the government to pass a law to protect same-sex couples and, moreover, same-sex couples enjoyed high social acceptance.

In the cases against Russia and Romania, by contrast, the court has had to grapple with domestic social disapproval. Eurobarometer indicated that a significant majority of Romanians (63 per cent) held negative views about homosexual behavior. And, according to statistics provided by the Russian government, 80 per cent of Russians are against same-sex marriage and 20 per cent believe homosexuality a disease. Following Oliari, Russia and Romania could point to the supporting reference in the ruling to ‘the sentiments of a majority of the Italian population’ to support their decision not to recognise same-sex unions.

The court however rejected their claims, noting that ‘democracy does not simply mean that the views of a majority must always prevail’. This passage sounds the death-knell to attempts by conservative states to shield their inertia by pointing to low social acceptance of same-sex couples.

Generalised right

There is now a right to same-sex registered partnerships: civil unions, civil partnerships or similar laws allowing same-sex couples to register and gain a set of rights and benefits. This doctrinal point is also a far cry from the narrowly tailored decision in Oliari: the judgment against Russia spoke to a generalised right to ‘a specific legal framework’, with a required minimum content.

The court was alert to the dangers of handing reluctant states a blank cheque. It therefore specified that not any law would be compatible with the convention: it must include meaningful content and some core rights (such as maintenance, taxation, inheritance and a duty of moral assistance). In other words, states must protect same-sex couples meaningfully.

The ruling against Romania this week adds another piece to the jigsaw. It specifically mentions civil unions and registered partnerships. This does away with the option of introducing scattered legal protections in civil codes and administrative laws (as the dissenting opinion of the Polish and Armenian judges would have seemed to allow).

Predictable resistance

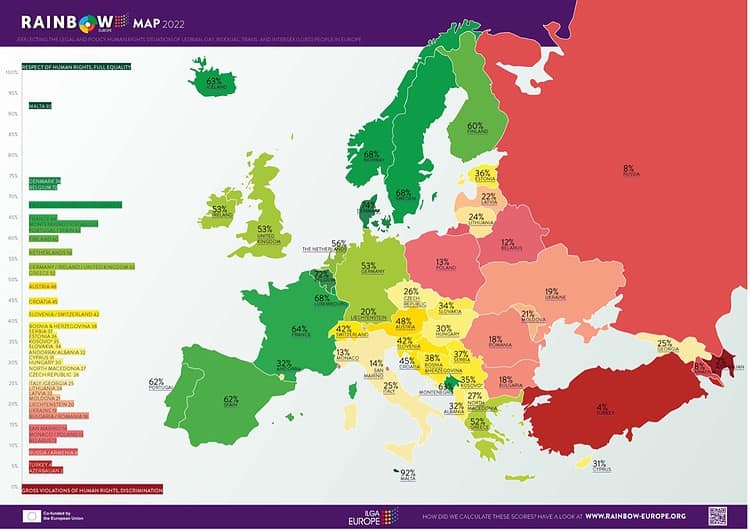

The spectre of low social acceptance in some European countries still looms large and will force the court to grapple with predictable resistance. The latest annual iteration of the Rainbow Europe map illustrates how it is navigating uncharted territory. LGBT+ rights sharply divide western- and eastern-European states. Azerbaijan and Turkey score as low as 2 and 4 per cent respectively on LGBT+ rights protection; Poland and Bulgaria perform a little better, at 13 and 18 per cent respectively, but their score is still remarkably low.

This will inevitably force the court to face challenges to its legitimacy, and accusations of ‘cultural imperialism’ from hostile quarters. The follow-up to the judgement against Romania will constitute a precious testbed for the ability of the court to survive the European culture wars in times of illiberal erosion.

Nausica Palazzo is an assistant professor in constitutional law at NOVA School of Law in Lisbon, working on family and constitutional law and sexual politics. She is the author of Legal Recognition of Non-Conjugal Families (Bloomsbury).