Meet Zsuzsa. A 28-year old high-school teacher in Budapest, she earns an average monthly wage of 187,000 forints (roughly €500). Despite her solid qualifications and hard work, Zsuzsa has not seen a pay raise since the cost-of-living crisis hit, leaving her struggling to make ends meet. A recent protest calling for higher wages for teachers marked her first time participating in something political. She had grown frustrated with the government’s refusal to increase salaries, even as inflation hit a record 25 per cent.

On top of low wages and high general inflation, Zsuzsa also faces rising housing costs. Her landlord recently increased her rent by 15 per cent, a shock she could barely absorb. Now she spends 85 per cent of her salary on rent and groceries, leaving little room for saving or leisure. High living costs have driven many of her neighbours out of Budapest.

Although Zsuzsa believes in democracy, she is losing interest in politics and feels that Hungarian democracy no longer represents the interests of her generation. As more and more of her colleagues and acquaintances begin to adopt xenophobic views, the idea of emigrating is growing on her. All in all, she is pretty pessimistic about the future of her country. In spite of all these challenges, Zsuzsa however remains optimistic regarding her personal future and believes she will be okay.

Politically disengaged

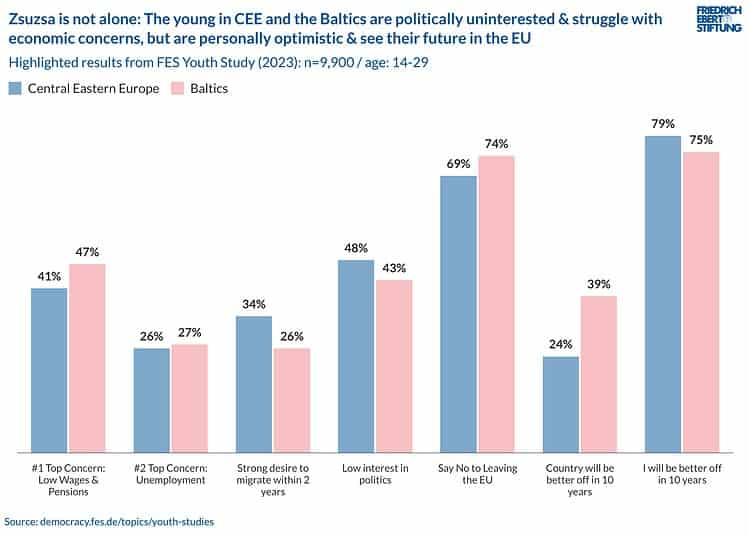

Zsuzsa is a fictional person, but her story is real and a poignant illustration of the challenges faced by many young people in central and eastern Europe (CEE) and the Baltic countries today. The latest representative survey by the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung of young people (14-29) in the region paints a picture of its youth as politically disengaged. Only one fifth consider themselves somewhat interested in politics, a mere 5.5 per cent very interested.

Compared with young people in western and northern Europe, these numbers are low. And no country’s youth (seven were surveyed) is more sedated than in Viktor Orbán’s Hungary: young Hungarians manifest the lowest political engagement in the region and are the most apolitical.

Their minds are elsewhere: young people in CEE and the Baltics are primarily concerned with low wages, unemployment, poverty and social inequality. Hungary and Poland have among the highest unemployment rates in the region, with young women particularly affected. They also have a disproportionately high number of young people who want to leave.

Having inhaled the neoliberal vision of self-optimisation, they believe in a future for themselves—that they can still achieve something if only they work hard enough. They no longer however believe that they can influence structures and have collective political impact, which is why they are politically disengaged.

On the flip side, what they lack in trust in domestic institutions, they make up for in trust in inter- and supranational ones. Even before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, more than half of young people in the Baltics placed high trust in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Similarly, most young people in CEE and the Baltics believe in the European Union and see their countries’ future within it. And, despite the authoritarian tendencies of some politicians in the region, the vast majority of young people remain committed to democracy and human rights.

Pawns in a power play

For the underlying causes of low political engagement of young people—such as mistrust in institutions and lack of faith in political parties—to be remedied, governments will have to start delivering to them as citizens. On the contrary, however, teachers such as Zsuzsa have become pawns in the Hungarian government’s power play with the EU.

In April, the state secretary of the Ministry of the Interior announced the government intended to increase teachers’ wages by 75 per cent … if only the EU made available the €5.8 billion funding from the Recovery and Resilience Facility it has frozen to press the Orbán government fully to reinstate the rule of law. At the same time, the government proposed legislation that would eliminate teachers’ public-servant status and increase their workload. This has been quickly dubbed the ‘Revenge Law’, perceived as punishment for the persistence with which Hungarian teachers have been demanding improvements to their living conditions.

Zsuzsa believes reforms are necessary and thinks it a good thing that no EU funds will flow until the conditions are met. At the same time, the need for policies to address the economic concerns of people such as her is urgent.

Zsuzsa’s typical tale shows how little political power young people in CEE wield. It is not surprising that she and her peers do not think they have a say in politics and refrain from engaging. At most, they end up being squeezed in the two-level game of governments blaming Brussels for domestic social grievances and Brussels in turn threatening the national administration.

Zsuzsa understands that she has become a pawn in this game and she supports the EU—for now. But how will she feel in 10-20 years when she is 40 or 50? Will she still believe in the European project? The data from this age cohort suggest otherwise: middle-aged and old people are less confident in the EU than the youth. If Zsuzsa stays in Hungary and the country does not reform, she might lose faith in that project—or vote with her feet by leaving for Germany.

Funding citizens

How can the EU sustain the commitment of citizens such as Zsuzsa? Social policy tangibly affects individuals’ life-chances. To escape the two-level game at some point, the EU will need to expand the policy toolbox, to find ways to address directly those such as Zsuzsa whose governments undermine democracy or simply do not take them seriously as constituents.

Direct funding mechanisms—or funding through intermediary institutions not under the control of governments—might offer an alternative. Rather than allocate money to governments that reallocate it according to sometimes-distorted priorities, the EU could be innovative and support individuals directly—providing proof that it really aims to deliver on the promise of equalising living conditions within the union.