Irregular pay is one of the criticisms levelled at platform companies. But some of the time there is no pay at all.

Employers and some policy-makers tend to be enthusiastic about the growth of the platform economy, expecting it to provide autonomy for workers while creating jobs especially for those ‘hard to employ’. Researchers have however sounded the alarm about the many challenges to work and employment conditions it creates, exacerbated by the pandemic: irregular pay, health-and-safety concerns and unpredictable working time. To these should be added the amount of unpaid labour performed by platform workers.

Unpaid labour is a systemic feature of platform work, inherent in its model of work organisation. Common on different types of platform—from on on-location delivery to online freelancing—we found it in different national and regulatory contexts in Europe.

Extraction of surplus

Unpaid labour involves the extraction of economic (‘surplus’) value from the workforce without compensation and usually consists of unremunerated, yet ‘productive’ activities performed by the worker and/or freelance beside their paid tasks. It can take the form of time spent waiting or searching for tasks or orders, travelling between gigs or building a reputation.

Although unpaid labour may be a feature of jobs elsewhere (think of freelance creative workers), unpaid labour within platforms is distinctive. It is not an unintended outcome but stems from how platforms govern labour to match clients with workers through digital intermediation: algorithmic-based optimisation, performance ratings (metrics and reviews) and the processing of data on workers and clients.

To give one example, platform reputation systems based on ratings are unidirectional, with only workers and not clients held accountable. Yet workers are highly dependent on good ratings to sustain work on a platform. This allows unfair client behaviour, such as demanding extra work be done for free, to go unchecked and increases the burden of unpaid labour.

Forms of unpaid labour

Two forms of unpaid labour are common within the platform economy:

- time-based—including unpaid overtime, waiting time, time spent searching for tasks, travelling to work and between jobs and unpaid breaks at work;

- non-time-based—including work intensification and pay-to-labour, such as platform fees and purchasing equipment.

Comparison of two on-location food-delivery platforms—Deliveroo and Takeaway—has shown that the extent of unpaid labour required from workers depends on employment status, the payment system (piece-rate or hourly-paid) and the platform’s use of new digital-intermediation technologies to govern labour. Algorithmic control systems decide to whom and how to allocate work in an efficient way: they analyse performance ratings, metrics and data collected from clients and users to make decisions about allocation of tasks and worker retention.

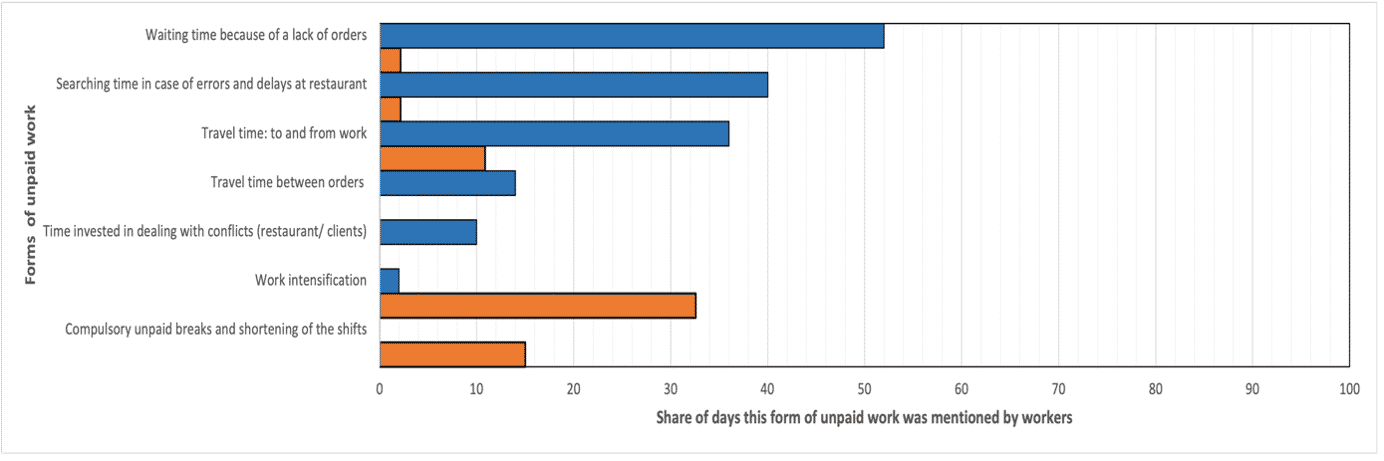

Unpaid labour in general, time-based in particular, is undertaken more often by self-employed piece-rate workers (Deliveroo) than by the hourly-paid (Takeaway). The latter, however, still experience a considerable burden of non-time-based unpaid labour, such as shortening of shifts without compensation and squeezed shifts, resulting in work intensification (Figure 1).

Figure 1: prevalence of unpaid labour on on-location labour platforms, Deliveroo and Takeaway (share of person-days, by form of unpaid labour)

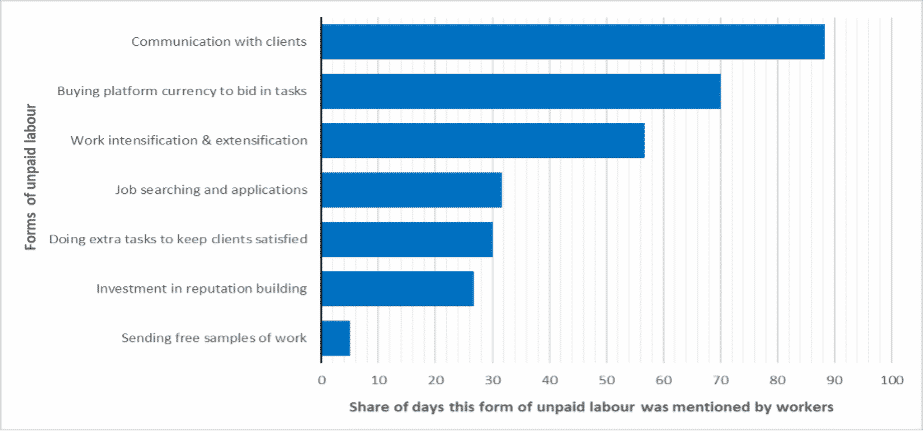

For the remote work platforms we analysed (Upwork and Malt), while unpaid labour may include non-time-based forms, such as payment of platform fees and commissions, time-based forms prevail (Figure 2). They are directly linked to long and unsocial hours spent on the platform to augment reputation ratings, which are specific to the platform and may thus ‘lock in’ freelances to it.

Reputation is essential for freelances to develop their career and portfolios and establish economic transactions and relations with clients in the market more generally. This calls for policy interventions to extend protection for different forms of labour under European Union competition law.

Figure 2. Prevalence of unpaid labour on remote labour platforms: Malt and Upwork (share of person-days, by form of unpaid labour)

Spillover effects

Our research indicates that unpaid labour not only affects income but has much broader negative consequences for workers and labour markets. Unpaid labour in the different forms revealed in our study can have various spillover effects on working lives.

Work intensification leads to poor health and wellbeing by impairing physical health and job satisfaction. Investing one’s own money and equipment when there is a poor return because of centralised algorithmic decision-making can lead to lack of autonomy, income insecurity and, possibly, precarity. Unpredictability related to working longer and unsocial hours disrupts work-life balance and accentuates conflicts.

Finally, in a context of increasing competition for assignments, unidirectional and non-portable ratings may enhance clients’ authority over workers. This ultimately exacerbates power asymmetries in favour of work providers, severely limiting participation and workers’ voice as important features of democracy at work.

Legislative initiative

The European Commission is about to table a legislative initiative on improving platform workers’ working conditions. The policy debate on possible solutions must recognises that unpaid labour is built into the way the platform economy operates. Our research shows that unpaid labour leads to an overestimation of the value generated by platform work and an underestimation of its costs, as completion of paid tasks does not encompass workers’ entire investment of time and (their) money, effectively lowering earnings.

Revealing the extent of unpaid labour inherent in platform work sheds new, and critical, light on the claims made by platforms about their positive employment effects. Labour platforms provide easy access to paid work but they also rely heavily on unpaid labour for their profits. Limiting unpaid labour within platform work could generate further, paid employment possibilities.

Markieta Domencka, Karol Muszyński and Lander Vermeerbergen contributed to this piece. The background research has received funding from the EU’s Horizon programme (ResPecTMe—grant no. 833577) and the Flemish Research Council (G073919N).