As policy-makers weigh their options after a devastating year, trade ‘liberalisation’ has been presented as a costless path to economic recovery. Yet, with the Foreign Affairs Council of the European Union and G20 labour and employment ministers meeting in late June, what evidence supports this view?

Scrutiny of the biggest proposal on the global table—a trade agreement between the EU and the south-American bloc Mercosur—reveals a less upbeat story. Trade liberalisation is costly on many levels and may lead to slower growth and higher inequality, unless buttressed by expansionary macroeconomic and active industrial policies.

In a working paper we show that the claims in favour of the EU-Mercosur agreement do not take account of critical challenges faced by EU economies, such as persistent unemployment and rising inequality. Duly considered, the outcomes for EU countries may well be negative.

Different priorities

The agreement would, over 15 years, remove tariffs on 92 per cent of EU imports from Mercosur and 91 per cent of tariffs on Mercosur imports from the EU. This may seem a good deal but these numbers obscure the different priorities assigned to industrial and agricultural products in the two regions: the EU would liberalise imports of industrial goods more than agricultural, while Mercosur would do the opposite. This is where the trouble starts.

According to the latest projections, over the same period the agreement would give the economies of the EU and Mercosur a one-time boost of less than 1 per cent. A deeper look at the background studies reveals that these negligible gains depend on many unrealistic assumptions favourable to the agreement, such as full employment, consistent inequality and given productivity. Thus even though some of the most critical problems faced by economies in the EU and Mercosur are assumed away, only paltry benefits are forecast.

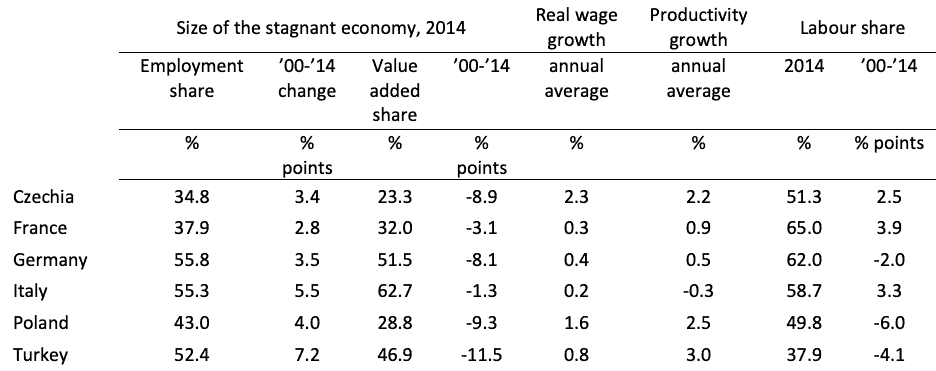

The projections also overlook critical, accumulating sectoral imbalances, affecting productivity, wages, employment and, ultimately, growth. Our research shows that since 2000 most jobs in Germany, Italy, France, Poland and the Czech Republic have been created in ‘stagnant’ sectors (see table), with low productivity and low wages, while value added has been increasingly generated in ‘dynamic’ sectors, with high productivity and high wages.

The stagnant economy

Typically, manufacturing and other industrial sectors have downsized compared with retail and other services. In Germany, Italy and France, this deindustrialisation has been one of the main causes of the ‘secular stagnation’ of gross domestic product and productivity. It is also a major cause of the increasing inequality observed in most EU countries. This is clearly not sustainable for those seeking full employment—and it is the opposite of the path developing countries must take to raise living standards.

Exacerbating adverse trends

Trade liberalisation has however contributed—albeit not alone—to these adverse trends and is likely to exacerbate them. It has promoted specialisation and entrenched competitive advantage in EU economies too. In the last few decades, most of the latter have progressed in advanced-technology sectors, such as vehicles, pharmaceuticals, information and communication. This allowed them to gain advantage in the global arena but created a more vulnerable labour market, pushing surplus labour towards poorer-paying, stagnant sectors.

The agreement might thus accelerate productivity in the EU’s dynamic sectors by promoting their exports but would be unlikely to generate the demand needed to stop deindustrialisation and the movement of labour toward stagnant sectors. The distributional imbalances and the risk of secular stagnation would likely worsen, especially because the agreement would do nothing to protect workers’ economic security.

There are environmental concerns too. First, the projected expansion of agri-food and mining in Mercosur could contribute to land use, deforestation and higher carbon emissions. Secondly, the technological and competitive asymmetries between the EU’s advanced economies and other economies in the EU and Mercosur would create a trade-off between environmental and developmental outcomes—exactly what policy should avoid in the face of the climate challenge.

For example, Mercosur countries enduring tougher competition with advanced EU economies would face pressure to reduce their production costs, by suppressing wages, and to forgo investments in green technologies. Such perverse incentives would deter them from making green transitions.

Powerful vehicle

Properly managed, trade expansion can be a powerful vehicle of economic development and technological upgrade, by easing foreign-exchange constraints and enabling economies of scale. But that must be matched by macroeconomic policies which sustain effective demand, rebalance income distribution and enable investments critical to easing (as against ignoring) the environmental constraints. Without such policies, trade liberalisation is likely to further economic and social polarisation.

Standard trade projections can paint rosy outcomes because they ignore the macroeconomic context of trade policy. In a time of global economic upheaval, heeding such advice is more dangerous than ever.