Unlike previous economic crises, the current crisis has disproportionately affected women’s employment in the European Union. This is not only reflected in significant job losses in female-dominated sectors of the economy, but also—perhaps more strikingly—in poorer working conditions, greater financial fragility and further work-life conflict for women.

Between March 2020 and February 2021, the number of unemployed in the EU rose by around 2.4 million, of whom more than 1.3 million were women. Female unemployment increased by 20.4 per cent, against 16.3 per cent for men.

Beyond job losses—dampened by the short-time work schemes in place in almost all EU countries—the impact of the pandemic on employment is evident in the fall in hours worked. Between the last quarter of 2019 and the second quarter of 2020, the drop in total hours worked in the main job was again more marked for women (-18.1 per cent) than men (-14.3 per cent).

Already-existing imbalances

This disproportionate impact on women has a lot to do with already-existing gender imbalances straddling sectors of the economy. ‘Social distancing’ and lockdown measures have hit most intensely services requiring direct contact with people, where teleworking is not an option: accommodation, food services, tourism, retail, entertainment, domestic work and so on.

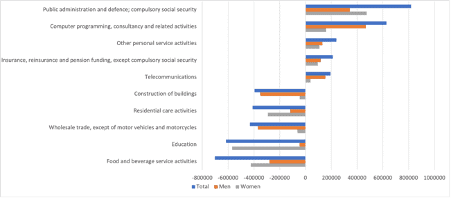

Because women account for 61 per cent of workers in these sectors, they have been more exposed to redundancy, temporary layoffs and reduced hours: only in retail and entertainment did men suffer more job losses between the last quarter of 2019 and the third quarter of 2020 (see chart). In food services and accommodation—undoubtedly the worst hit—880,000 jobs were lost during this period, 535,000 of them held by women.

Male-dominated sectors, such as industry and construction, have not been immune to the crisis. Not only was the initial drop in activity less intense, however, but they also rebounded more quickly and strongly in the following months than contact-intensive services, whose decline has been just as dramatic during the second and third waves of the pandemic.

In addition, between Q4 2019 and Q3 2020, job creation systematically favoured men over women (except in the public sector). Notably, hires in telecommunications and computer programming benefited 630,000 men but fewer than 170,000 women.

EU-27 job losses and gains, Q4 2019 to Q3 2020 (Eurostat)

In the longer term, women’s employment is likely to deteriorate further. With the end of support provided by short-time work schemes and other public measures, sectors unable to recover quickly and strongly are likely to face massive company failures and an upsurge in unemployment.

According to the European Commission’s forecasts, services will take longer to recover, barely reaching pre-crisis levels at the end of 2021—meaning that women could experience effects from the crisis more enduring than for men. In addition, research suggests that, once the furlough schemes come to an end, non-standard workers are more likely to be made redundant than full-time employees. Because women are over-represented in this category—constituting the great majority of part-time workers—they are also more at risk of being laid off in the months to come.

Most undervalued

Women make up the majority of frontline workers: 76 per cent of healthcare workers, 82 per cent of food-store cashiers, 86 per cent of personal care workers, 93 per cent of childcare workers and teachers, and 95 per cent of domestic cleaners and helpers. During the crisis, these workers experienced an increased workload, with greater exposure to health risks and emotional demands than experienced by any other category of worker. Yet, despite arduous working conditions, these occupations are also some of the most undervalued—including under-paid—in the EU.

Moreover, even though extraordinary measures to protect workers and companies during the crisis have cushioned income losses, women have been experiencing greater economic difficulties than men—probably due to prior inequalities. Because women are over-represented among low-wage workers in the EU, making up 58 per cent of minimum-wage earners and 62 per cent of workers earning substantially less than the minimum, wage-replacement measures—even where generous—may have been insufficient to guarantee their economic security during the pandemic. Indeed, according to Eurofound, more women have reported difficulties making ends meet and maintaining their standard of living during this time: 58 per cent said they could not get by for more than three months, compared with 48 per cent of men.

Yet because of the severe economic strain suffered by many companies during the pandemic, gender-equality measures will, at least in the short term, likely be perceived as a secondary issue by company boards—especially since across the EU women make up only 34 per cent of board members and just 9 per cent of chairs. Governments, meanwhile, might be inclined to give companies some slack on their obligations regarding pay reporting and other measures to tackle pay inequalities between men and women. In France, for instance, companies are already postponing adoption of equality plans to reduce the gender pay gap—despite the demonstrated economic benefits of so doing.

Unequally shared

The generalisation of teleworking, together with the closure of schools and childcare because of lockdowns, has increased care needs within households during the pandemic. Yet old habits die hard—especially when it comes to gender roles—and this heavier burden has not been equally shared.

According to preliminary research, women have been the ones to take on the bulk of unpaid care, spending far more time than men caring for children and doing housework (53 hours versus 37 hours). The difference is even more staggering looking only at women with children: they have been spending 85 hours per week on these tasks, compared with 51 hours for men.

This increase in domestic and care responsibilities has left women struggling to balance their work and personal life. Seventeen per cent of women with children reported that it was hard for them to concentrate on their job because of their family and 13 per cent said their family prevented them from giving time to their job. Men, by contrast, seemed largely unaffected, with only 6 and 3 per cent of them respectively so affirming.

Data also confirm that women have been more likely to reduce their working hours to provide childcare during the pandemic. This forced ‘under-involvement’ at work could have lasting consequences for women’s careers, since it could jeopardise their chance of being promoted over their male counterparts who have not felt the same constraints. In addition, this puts some women on the frontline of future job cuts.

Real concerns

Concerns that the pandemic will reverse recent gains in gender equality in the labour market are thus real and need to be addressed. To avoid long-lasting effects on women’s employment that would turn the economic downturn into a true ‘she-cession’, the EU and its member states need to ensure a gender-sensitive recovery. That entails mainstreaming the gender dimension in their recovery plans and including specific actions to tackle existing inequalities, such as the gender-employment and pay gaps among many others.

Overcoming the crisis should not sideline the fight for gender equality—but reinforce it.