The idea that corporate tax cuts could enhance economic growth has long occupied researchers. The claim that a tide of corporate tax cuts will lift all boats through more growth has been a core element of ‘supply-side’ economics, from Ronald Reagan’s 1980s United States presidency to the opportunistic power politics of his latter-day successor, Donald Trump. And in current economic-policy debates on how to recover from the pandemic, that notion has found political advocates in a number of European countries—including the conservative and liberal parties in Germany, facing into the autumn Bundestag elections.

The putative effects of corporate taxation on growth are also relevant to the debate, recently pursued through the G7 and the G20, on a global minimum tax rate for multinationals and—if such there be—how high a threshold to set. While the new US administration under Joe Biden argues that the growth effects of previous tax cuts have often been exaggerated, those advocating caution counter that a minimum tax will have a negative impact on growth—and the higher the minimum the greater the impact.

Economic theory

One camp argues that tax cuts will increase profit margins, which will enhance investment and so growth and employment; the other doubts this mechanism, pointing to the opportunity costs of reduced tax revenue. But what does economic theory suggest?

In the neoclassical growth model associated with the veteran US economist Robert Solow, long-term growth arises from exogenous technological progress. Tax policy can then ‘only’ affect the level of gross domestic product and the transition to steady-state growth. Lower corporate taxes encourage corporate saving and investment and so imply higher GDP in the long run.

In recent, ‘endogenous’ growth models, corporate tax cuts can also have a positive impact on the long-run growth rate, by boosting total-factor productivity (arising over and above discrete capital and labour inputs) and innovation. Since the ultimate tax incidence would be borne by natural persons (the shareholders, workers and consumers) anyway, and since passing on taxes is associated with efficiency losses, some standard models argue that the optimal corporate tax rate should therefore be zero.

Others however argue that higher capital taxation can promote economic growth, by shifting the tax burden away from labour and/or by financing productive government spending. Moreover, as corporate tax cuts tend to benefit richer households with a lower propensity to consume, they generate only weak growth from the demand side. The supply-side effects are also expected to be much weaker when they benefit higher-income households.

Nevertheless, the dominant theoretical prediction, on which most of the empirical work is based, remains that corporate tax cuts promote growth.

Empirical studies

Empirical studies have examined the growth effects of corporate taxation for different country groups and time periods, using different datasets and econometric methods. Relevant factors include how studies measure tax changes (whether in the statutory or effective rates or the revenues arising in relation to output), how they address endogeneity (because growth in turn affects tax revenues), whether they focus on short or long-term effects, which countries and periods they select and whether they control for other budget components (other taxes or government expenditures).

A careful reading of the literature suggests that the reported results vary considerably. Some studies find substantial and robust positive growth effects of corporate tax cuts. But others report significantly negative, non-significant or mixed results.

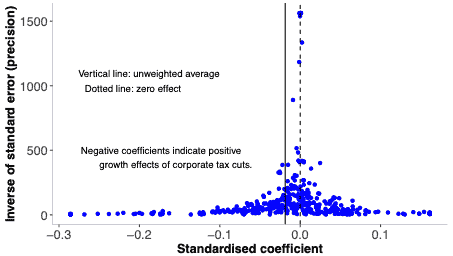

In a meta-review, we collect 441 estimates from 42 primary studies. We apply the meta-analysis toolbox to analyse how large the precision-weighted effect (attaching greater significance to studies with more precise results) turns out to be when corrected for factors that may introduce a bias. And we provide model-based results as to the impact of certain data and specification choices on the estimates reported in the literature.

Positive growth effects imprecise

The chart below shows that the results are indeed widely scattered and have varying precision. The strongest positive growth effects of corporate tax cuts reported in the literature tend to be imprecise: they have large standard errors. The unweighted average across studies suggests that a one percentage point cut in corporate taxes is associated with an increase in economic growth of about 0.02 percentage points per year—a moderate but significant effect (a 10 percentage points cut in corporate tax rates would imply an annual increase in GDP growth of 0.2 percentage points).

This outcome could however be affected by selection in the publication process: study authors and journal editors might prefer results which conformed to theory and were significant, leading to publication bias. Looking at the correlation between the estimated effect size and its standard error can help identify whether such a bias exists—in its absence, econometric theory suggests there should not be a systematic correlation.

We find though a negative and significant correlation, implying that the growth effects of corporate tax cuts are over-reported. When we control for the influence of this publication bias, we are left with no positive effect of corporate tax cuts on growth rates—we can no longer reject the hypothesis that the effect is zero.

We confirm this finding by using several approaches to detecting publication bias. All our estimates find an insignificant effect of corporate tax cuts on economic growth, near zero. Publishing a statistically-significant, growth-enhancing effect of a corporate tax cut is four to five times more likely than publishing a non-significant effect.

Further insights

Our study provides some further insights into the factors that are relevant in explaining higher or lower growth effects of corporate tax cuts.

First, country samples (members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development or non-OECD countries) do not appear to make a significant difference—thus caution is warranted regarding claims that corporate tax cuts would have a significantly different effect on growth in developed countries compared with emerging markets. Secondly, recent studies tend to find fewer growth-enhancing effects from corporate tax cuts. Thirdly, controlling for government spending seems relevant: tax cuts are somewhat more favourable to growth when government spending is not cut at the same time. This result is consistent with endogenous growth theory, which suggests that using government revenues from taxing firms to increase (productive) government spending can have positive effects on growth.

Our results suggest that the prominent role given to corporate tax cuts in policy debates is exaggerated. Tax cuts have certainly stimulated international tax competition in recent decades, but they do not seem to have enhanced growth.