As the pandemic gathered strength across Europe last year, several governments promised—and some gave—‘danger money’ bonuses for frontline workers in health and social care. But these only treat the symptoms, not the underlying problems. Bonuses and even higher wages come nowhere near addressing the fundamental concerns of care workers, which go well beyond remuneration.

These extraneous issues in care—insufficient funding, marketisation and privatisation, the ‘brain drain’ and understaffing—are longstanding. Should they remain unresolved, then fresh labour unrest in the sector in post-pandemic Europe is scarcely avoidable. An analysis of the dynamics and patterns of prior episodes makes this clear.

Public support

Unrest in the sector isn’t new. This might be surprising, as care work is generally considered a ‘labour of love’: it is expected that workers find the work they do intrinsically rewarding. Moreover, the loyalty of care workers towards individual beneficiaries, and their professional ethics, might make it morally difficult for them to turn to industrial action.

If care activities are recognised as ‘work’ and not a ‘moral obligation’, however, then alliance-building between workers and care recipients, and their relatives, can be fostered. General empathy for the dedication of care workers also opens the way to mobilisation of public support and coalition-building with community and progressive movements.

Strike actions in health and social care are infrequent but they are eruptive. More generally, strike action in the sector largely follows the pattern for the country—higher where this is above average but more muted in less strike-prone countries. Among the latter, however, industrial action in health and social care is (alongside education) cracking labour quiescence, becoming almost a synonym for trade union protest action.

The repertoire for collective action by health and care workers is also diverse, going beyond strikes and working-to-rule. It extends to demonstrations, symbolic protests and mass resignation campaigns. This is in light of the ‘moral dilemma’ mentioned, with workers seeking to minimise the impact on users, while constraints on industrial action are anyway often pretty strict—care work being regarded as ‘essential’ in most countries, so an emergency service can be guaranteed.

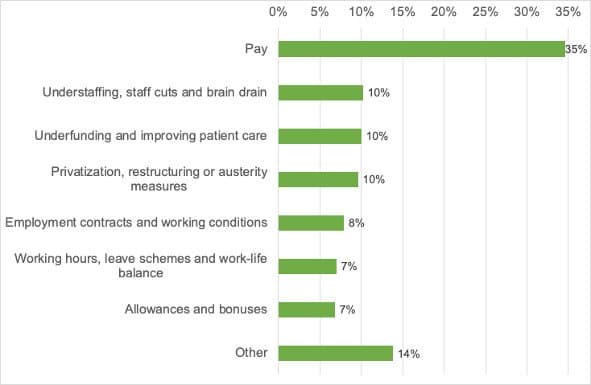

Moreover, the claims of health and care workers are multi-faceted (see chart). Issues such as underfunding, understaffing and stress are rooted in the marketisation of the sector or in the austerity policies governments have (inchoately) pursued in the aftermath of the finance-led crisis of capitalism. The fact that several professions in care are predominantly female not only adds to the ‘feminisation’ of industrial action but—even if workers’ complaints are not limited to wages—also brings the gender pay gap into play as a source of grievance.

Demands and grievances in health and social care in Europe, 2008-2021

During the pandemic temporary restrictions on the right to strike for ‘essential workers’ have ben put in place in countries such as Portugal and Romania. The ‘moral dilemma’ of care workers has become particularly compelling, with their professional accountability towards society and public-health protection at stake. Labour unrest seems to have been relatively dampened in countries in central and eastern Europe.

Yet, overall, the pandemic has generally not been a harbinger of labour quiescence. Strike actions or the threat of them have continued, and demonstrations and rallies have taken place in several countries. And even if their relative importance may have decreased somewhat, this does not apply to symbolic protests. Online campaigns with beaming images of care workers, as photos or videos, with slogans projected on to key buildings in the public arena, have proved a minor, but nonetheless innovative, augmentation of the action repertoire.

Shifting agenda

In the eye of the Covid-19 storm, the agenda has partly shifted, however temporarily. The pandemic has framed more prominently care workers’ longstanding claims, while immediate concerns about employment terms and conditions have come strongly to the fore.

Unsurprisingly, this applies in particular to health-and-safety issues, such as lacking or inadequate personal protective equipment and the need for psychological support in respect of mental wellbeing. Long working hours have highlighted staff turnover and enduring shortages, while increased workload has been associated with non-standard employment contracts and the diluting of policies on (sick) leave and work-life balance—on top of already-precarious working conditions in many cases.

The responses by employer associations and governments have been uneven. In several countries, bargaining rounds in private or public care have resulted in collective agreements setting increased pay and improving working conditions. Albeit to different degrees, some governments have swiftly agreed, or promised, additional funding to these ends or to hire more staff.

Above all, however, governments have turned to paying one-off Covid-19 bonuses in recognition of the ‘unique efforts’ of care workers during the pandemic. Yet, even though governments are fulfilling one immediate demand, bonuses are no more than a cosmetic gesture: they do not address entrenched grievances and claims. And bonuses which leave a bittersweet taste can perversely be demotivating.

Political opportunities

The pandemic has opened up political opportunities, in terms of budgetary capacity, for trade union demands in health and social care. It remains to be seen, however, whether this will imply a historical turning point in the organisation and delivery of care from its increasingly neoliberal conception. Will today’s interventionist governments also refrain from rampant marketisation and privatisation, returning once more to a public, non-profit care service?

In several instances, (the threat of) strike action or other forms of labour unrest have been necessary to put, or retain, the pressure on governments. This will not change in a post-pandemic world coping with ‘long Covid’. Industrial action by organised care workers might set the example for other (‘essential’ or ‘frontline’) workers outside care in coming struggles, further delegitimising the neoliberal discourse.

Much depends, however, on the presence and dynamism of an imaginative, forward-thinking and responsive trade union leadership—able to connect labour unrest in health and social care with other struggles in and beyond the workplace.