Germany’s sustained current-account surplus is not only bad for others in Europe and beyond—it is bad for almost all Germans too.

The German economy has been running persistently high current-account surpluses for more than 15 years. Over the last decade, the surplus was between 6 and 9 per cent of gross domestic product, mainly because Germany exported much more than it imported. This is a drag on other countries’ exports and employment and can also lead to financial imbalances.

A large majority of economists outside Germany thus see the surpluses as a serious threat to macroeconomic stability. The European Commission, the International Monetary Fund and the United States government have repeatedly called for a rebalancing. So far, however, none of the various German governments in power since the early 2000s has seen the need to take action.

In a recent paper for the Forum for a New Economy we argue that it would be better for Germany finally to find genuine answers as to how the surplus can be significantly reduced. This would not only help current-account deficit countries in Europe and beyond, which could boost their exports and employment as well as reduce their external debt. The vast majority of the German population would also see major benefits from a reduced surplus, which would be accompanied by higher incomes for households and increased public investment.

Three myths

The domestic debate is shaped by three myths, which make the search for ways out more difficult. First, it is often claimed that, historically, export orientation has been an important element of the German growth model. Yet until the mid-2000s Germany’s current-account balance hardly ever exceeded 4 per cent of GDP, from the founding of the German empire in 1871.

Nor can these surpluses be considered as the outcome of an economic equilibrium. In particular, higher precautionary savings driven by demographics—often cited as a crucial factor—explain less than a percentage point of the surplus, according to estimates by the IMF. From the IMF’s perspective, this makes Germany the only large country to have run a permanent, excessive, current-account surplus for many years.

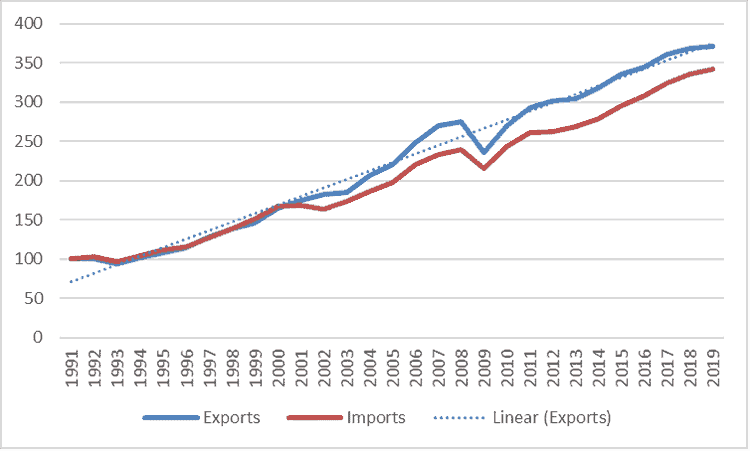

Finally, this cannot be put down to pronounced export strength. The high surpluses are better attributed to below-trend imports. Especially in the first years of the millennium, imports fell dramatically as domestic demand stagnated. The resulting import gap has not been closed since (Figure 1).

Figure 1: real exports and imports (1991=100)

But how did the stagnation in imports come about? A look at the three domestic sectors—households, corporations and government—which comprise the German economy shows why.

Wage restraint

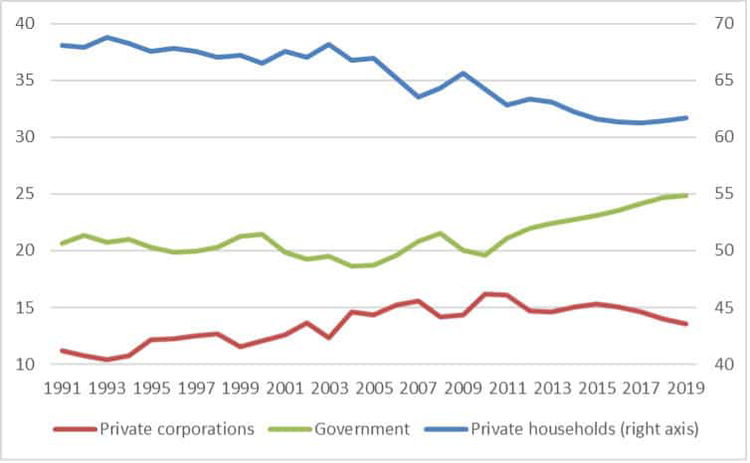

Households have lost around eight percentage points of national income since the mid-1990s (Figure 2). Initially, in the 1990s and 2000s, they lost out to the corporate sector, whose profits rose mainly due to wage restraint and the expansion of low-wage employment. That sector, however, hardly increased spending but retained a large proportion of profits. This was attractive for tax reasons after the reform of corporation tax in the early 2000s and increased firms’ independence from external financing via capital markets.

Since the 2010s, households have lost income share especially to the government sector. Despite strongly rising tax revenues, however, government has pursued fiscal surpluses rather than investment, due to the German ‘debt brake’ (Schuldenbremse) and the philosophy of balanced budgets (schwarze Null).

Figure 2: Sectoral incomes as a share of gross national disposable income

Furthermore, due to its high export surpluses, Germany is very dependent on what happens outside its borders. Because the high German surpluses are mirrored by high deficits in other countries, a latent danger of debt crises and protectionist trade policies is the consequence. In turn this threatens prosperity and employment in Germany as well.

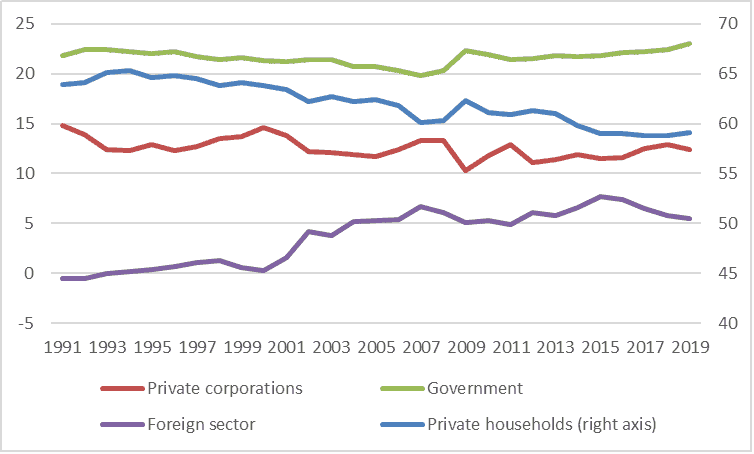

Figure 3: sectoral expenditures on consumption and investment as a share of GDP

To reduce the German surplus the import gap must be closed—this means bringing domestic demand and production of goods and services back into alignment. For the overwhelming majority in society, this would be a better use of the strength of Germany’s economy, compared with the accumulation of insecure and low-return financial assets abroad.

Investment orientation

A massive strengthening of public investment, as well as production of public goods and services, will have to play a key role in rebalancing the German economy. There are increasing financial needs, particularly in the socio-ecological transformation and transport infrastructure, as well as in education and health, which should be assuaged step by step, partly financed by public debt. For this, an investment-oriented reform of the debt brake would be helpful.

At the same time, there is considerable leeway for private households to benefit once again more strongly from economic growth. This would increase domestic consumption in relation to exports. One approach to achieving this is through enhancing wages—setting a higher minimum wage, strengthening collective bargaining, reducing working hours with partial wage compensation and improving pay and staffing in the public sector. The other is through progressive reforms of the tax and transfer systems.

With a suitable package of measures, the German current-account surplus could possibly disappear as quickly as it came in the early 2000s. There is no reason why the ‘German growth model’ should not be reversible within a decade—but this does require decisive action.

This article is based on the study ‘How to reduce Germany’s current account surplus?’, commissioned by the Forum for a New Economy and published in January

Jan Behringer is head of the economic policy unit at the Macroeconomic Policy Institute (IMK) of the Hans Böckler Foundation, Düsseldorf. Till van Treeck is a professor and managing director at the Institute for Socio-Economics at the University Duisburg-Essen. Achim Truger is also a professor at the institute and a member of the German Council of Economic Experts.