Amid the market turmoil in March 2020, the president of the European Central Bank, Christine Lagarde, said the bank was ‘not here to close spreads’—only to do a subsequent U-turn, announcing that it remained ‘fully committed to avoid[ing] any fragmentation’ in bond markets. The selling of Italian and other southern-European bonds which followed Lagarde’s initial remark undoubtedly showed her how dangerous such comments can be, especially in a market environment of uncertainty and stress.

Despite an echo here of her predecessor Mario Draghi’s 2012 ‘whatever it takes’ declaration—this time expressed as ‘no limits to [the] commitment to the euro’—the question remains as to how determined the ECB will be, and for how long, to avoid centrifugal forces in the eurozone taking over again in the future, not least after the judgment of the German constitutional court in May 2020 insisting that it justify its bond-buying programme. Yet there is surprisingly little recognition of the need for the central bank to close spreads in a single-market and currency regime.

The closing of spreads is fundamental because of the role of government bonds in central banks’ open-market operations and their distinct quality as a safe asset. This makes government debt the backbone of most fixed-income security markets. Bank of International Settlements data for the second quarter of 2020, for example, show that government debt accounts for 49-51 per cent of total debt securities in the United Kingdom, Germany and France (with no significant change due to the pandemic).

As safe assets, government bonds provide the benchmark yield curve for other securities and affect the trajectory of the overall credit curve in the economy. In other words, any debt security issued in the market is being priced against government bonds. For private actors, this means the terms on which they will be able to gain access to capital markets will depend not only on the performance of their company but also on government bond yields. Hence the problem: how to compete on fair grounds against firms in other countries within a single market if benchmark rates differ?

Automotive industry

A prime example is the automotive industry. Being capital-intensive, access to capital markets is a critical competitive factor. And for several producers sales are largely financed by credit from a manufacturer-owned bank: half the vehicles sold by BMW or Daimler are financed or leased by BMW Bank or Daimler Financial Services. Car manufacturers refinance their financial divisions mainly through the issue of bonds, as their annual reports indicate.

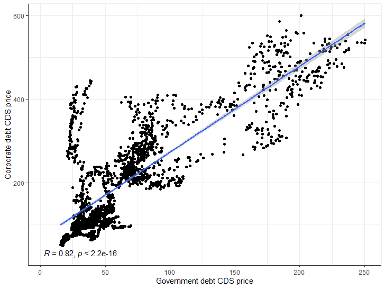

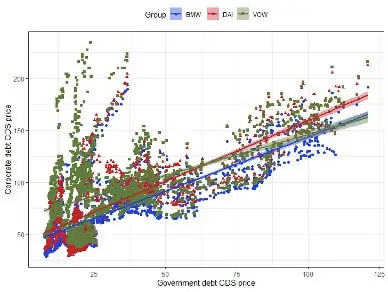

In securing access to capital markets, even for highly internationalised automobile firms the national benchmark rates still constitute a critical reference point. Figures 1 and 2 correlate the prices of credit default swaps on five-year senior debt for the some of the main European car manufacturers and their respective national governments between 2009 and 2018. Figure 1 shows the correlation of CDS prices of five-year senior debt of Renault and the French government, figure 2 that of the German manufacturers BMW, Daimler and Volkswagen and German government debt. CDS prices indicate how much investors would have to pay, in basis points, for the insurance of debt default (which is inevitably tied to the prices of corporate bonds and therefore yields). The higher the prices, the more demand there is for CDS, which means more market participants sense a higher risk of default or are actively betting on it.

For Renault, the correlation between CDS prices on its own debt and that of the French government is a staggering 0.82, while in the German cases the correlation between CDS prices is 0.75-0.78, which is still very significant. Volkswagen is somewhat special, as the ‘Dieselgate’ scandal (the company having been found to have manipulated trial data on exhaust emissions) produced quite a few outliers; until just before the scandal erupted, however, the correlation stood at 0.77.

Figure 1: Correlation of CDS prices for French government and Renault corporate debt (basis points)

Figure 2: Correlation of CDS prices for German government and BMW, Daimler, Volkswagen corporate debt (basis points)

Particularly during the eurozone crisis, just how much spreads were distorting competition became apparent. The German business newspaper Handelsblatt, for example, reported in November 2012: ‘The car industry has to borrow tens of billions of euro every year to finance its cars. Differences in creditworthiness therefore open deep rifts. PSA and Fiat have been heavily downgraded by the rating agencies this year. German manufacturers, on the other hand, enjoy top marks: Daimler, BMW and Volkswagen now get money cheaper than governments in Madrid or Rome.’

Highlighting the deep divergence between the Germans and the rest, the author went on:

Italy’s largest industrial group is now paying 7.75 per cent interest for a four-year bond. On the other side of the Alps, BMW is practically getting money thrown at. The Munich-based manufacturer borrowed more than €20 billion in 2012 and paid a modest 1.25 per cent for its last bond. With an inflation rate of just under 2 per cent, investors are paying money to lend to BMW. As a consequence, BMW can offer leasing rates of less than €200 and make a new record profit. The competition is boiling … [The chief executive of Fiat] has already accused his arch-rival Volkswagen of causing a ‘bloodbath’ with its cheap financing, because Fiat has no chance of competing against its big German rival with the current credit rating differential, even if Fiat were to substantially increase its productivity. In Italy, the Turin-based company offers the Fiat 500 small car at 6 per cent interest, while VW counters with 0 per cent for the comparable Up model.

In other industries, whether capital-intensive or not, the story will be similar: the competitiveness of enterprises will depend on the benchmark rates of their national governments. In this context, it means that a well-managed firm in Italy may eventually find itself with the same refinancing conditions as a more poorly managed German firm, just because the latter is based a few hundred kilometres north.

In the automotive industry, differences in the terms at which the major European manufacturers were able to gain access to capital markets were a key factor in German firms expanding their market shares, with the knock-on effects of problematic trade imbalances. And of course, this is not just about the automotive industry but the entire manufacturing sector with its wider economic footprint.

Clear conclusion

Considering that the goal of the single market is a level playing-field for intra-European competition, the conclusion is therefore clear: without closing spreads there is no level playing-field and hence no point in having a single market. As in the domain of wage co-ordination, we face the paradox that for a market to function well substantial intervention by public actors (in this case the central bank) is a sine qua non.

Closing spreads would be technically very simple—politically, however, less so. Forward guidance would likely be sufficient: just as Draghi’s mere announcement of the Outright Monetary Transactions programme was enough to end speculation against government debt, communicating to financial-market participants that one policy objective of the ECB would be closing spreads to smooth the functioning of the single market would lead to portfolio adjustments which would almost immediately and automatically close the spreads. If this were not the case, the ECB would simply have to buy up more higher-yielding government bonds, which would increase the bonds’ prices and thus bring down the yields, until the spreads were closed.

From the political side, this would require that the ECB legally acquire the flexibility, as under the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme, to deviate from the capital key (the formula by which national central banks are allocated their capital contributions to the bank). That might face resistance from the remaining ordoliberal bastions in Europe—the ‘frugal four’ and northern allies—who would most likely express fears for ‘fiscal discipline’.

Following this line of argument, however, they would also have to drop their support for the single market and the single currency—since one cannot have spreads on government bonds and fair competition at the same time.

Patrick Kaczmarczyk works as a policy consultant for the Economic Forum of the SPD in Germany. Previously, he worked as a consultant for the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. (Views expressed are his own.)