Inequalities between men and women, including in their remuneration, have emerged as a central topic during the pandemic. Just under a year ago, the European Commission proposed a directive on pay transparency, intended to address some of the shortcomings of the European Union framework on equal pay. Indeed, the EU gender-equality strategy for 2020-25 envisages a range of measures to tackle the gender pay gap.

Performance-related pay, however, has received little attention at the EU level as a factor contributing to that gap. Yet recent research shows that such schemes are increasingly prevalent across the EU and that they contribute to pay inequalities, including between men and women. Legal frameworks on equal pay could address only some aspects of this issue, and more effective and comprehensive solutions need to be developed by policy-makers and the social partners.

Gaps exacerbated

Performance-related pay, or performance pay, links wages to workers’ individual performance, or that of their team or the firm at which they work. These schemes are used to incentivise workers and reward employees in a more flexible manner and are often less strictly regulated. While in principle this could break down existing inequalities, research shows that gaps between workers—including the gender pay gap—are generally exacerbated.

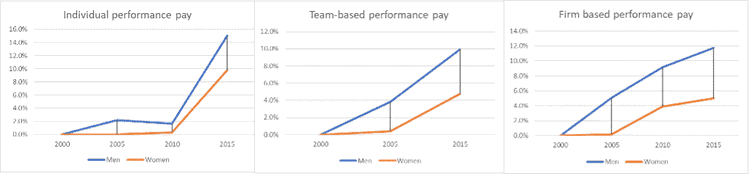

This is crucial, as those affected by performance pay increased from fewer than one-fifth of European workers in 2000 to around one-third in 2015. As the figure below indicates, this benefited men much more than women. Indeed for group-based performance pay, where workers benefit from the performance of teams or the firm as a whole, the gain for men was over twice as high as for women.

Increases (%) in performance pay for men and women relative to 2000

There are several reasons for women receiving less of this performance-pay premium. First, they are much more likely to work in positions where performance-pay opportunities are less available. They work in smaller firms, in sectors such as public and other services, or accommodation and food services, where profit-based schemes in particular are used much less. Women are also much more likely to work on temporary contracts and part-time jobs, where performance pay is lowest.

Secondly, performance pay is used more among the higher earners, both in terms of firms with high pay and the higher salary groups within a firm—again women are under-represented. Even when women do receive performance pay, they benefit less than men: at the higher wage rates, women’s bonus from being on performance pay is well below that of men.

Research does not support the notion that women themselves tend to abjure jobs linked to performance pay, purportedly because these may be more intense or stressful. More plausible is that performance-pay systems are more open to managerial discretion—especially when ‘performance’ is difficult to quantify—and can thereby entrench stereotypes. They are further given as part of a reward package and so mainly go to those workers already earning more: those on standard contracts and in high-skill occupations, the higher educated and, generally, men.

Indirect discrimination

Neither the EU gender-equality strategy nor the 2017-19 action plan on tackling the gender pay gap mentions these issues. Some performance-pay schemes that benefit men more than women could be considered to constitute indirect pay discrimination based on sex, prohibited by article 4 of the 2006 gender-equality directive. According to the case law (such as Kachelmann) of the EU Court of Justice, indirect discrimination may be present when a measure that is neutral on its face might nevertheless work to the disadvantage of a much higher percentage of women than men.

This could catch performance-pay schemes that favour men because, for example, they reward only full-time workers or male-dominated jobs within a workplace. The concept of indirect discrimination, however, can often be difficult to apply in practice, in terms of establishing appropriate comparator groups and the presence of particular disadvantage to women. It could also be open to employers to argue that differences in pay can be ‘objectively justified’, such as on the basis of certain business needs.

Furthermore, the prohibition of indirect pay discrimination will not be relevant in all cases. It applies only to pay differences between workers doing ‘the same work or work to which equal value is attributed’, and not to situations where inequalities arise because performance pay is available to those in higher positions. It will generally also not catch inequalities arising from firm size. It is a limited tool which does not offer a systematic approach to addressing the gendered effects of performance-related pay.

Effective measures

The proposed directive on pay transparency contains some helpful new provisions. For instance, it requires that employers with at least 250 workers must report—among other things—on the gender pay gap between categories of workers doing work of equal value, broken down by basic salary and complementary or variable components of pay. This does not however separate performance pay from other variable components of pay and about two-thirds of EU workers are engaged in enterprises with fewer than 250 workers.

The use of performance pay is likely to increase further and its contribution to gender inequality should not be ignored. More effective measures should be developed to fill the gaps in policy and legal frameworks. These could include provisions in statute or collective agreements to ensure that performance-pay schemes are transparent and gender-sensitive, awareness-raising on the gendered effects of performance pay, and data collection and research to understand these effects better.

Of course, performance pay is only one of various factors which contribute to gender inequalities in pay. Horizontal and vertical labour-market segregation, engagement in part-time and temporary work, the undervaluation of work typically performed by women and pay discrimination all add to the gender pay gap and those in overall earnings and pensions. The fact that women perform a greater share of unpaid care work continues to affect their position on the labour market and their pay. Gender-equality strategies must include robust and comprehensive measures to tackle these different dimensions of structural disadvantage.