Since July 2022, the European Central Bank has confronted the euro area with a rise in interest rates unprecedented in scale and speed. The effects of this policy are now being felt.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development is forecasting that this year gross domestic product in the eurozone will grow by just 0.6 per cent, down from 0.5 per cent in 2023. This is the weakest growth performance of any major economy.

Gross fixed-capital formation—investment—will be hardest hit, falling by 0.6 per cent in 2024. The ECB expects growth to pick up in 2025 (+1.6 per cent). But this was also its forecast for 2024 a year ago.

Macroeconomic tightening

The tightening of monetary policy, associated with high interest rates, has been reinforced by a restrictive fiscal policy. The ECB estimates that the partial withdrawal of support measures to address energy costs and wider inflation has led to a tightening of the eurozone fiscal stance—as reflected in the (cyclically-adjusted) primary balance—in 2023 and expects a more significant tightening in 2024. The fiscal-policy squeeze in the euro area is illustrated by comparing its budget deficit of 2.9 per cent of GDP in 2024 with that of the United States, where it will reach 5.3 per cent according to the Congressional Budget Office.

This poor economic performance is reflected in a faster-than-expected disinflation process. In September 2023, the ECB staff forecast for inflation in 2024 was 3.0 per cent. This month, the forecast was revised downwards to only 2.3 per cent, which is close to the target. For 2025, the inflation forecast of 2.0 per cent would be fully on target.

Another indication of the lack of dynamism in the euro area is the stagnation of bank loans to the private sector since autumn 2022. In line with this, the growth rate of M3 (a standard measure of the money supply) has slowed sharply and is now also close to zero.

Confusing metaphor

Taking into account that the effects of monetary policy are not immediate but have a lag of about one to two years, one could conclude that disinflation has been successfully achieved and that it is now time to move from a restrictive to a neutral policy. The ECB president, Christine Lagarde, however takes a different view. Asked by a journalist about the merits of a gradual rate cut, she replied with an elegant but somewhat confusing metaphor:

I would use the analogy of seasons and episodes. We are still in the holding season. We will move to the restrictiveness season, that will take a while. And once that season is over, we will move into a normalisation season.

Which suggests that ‘normalisation’ is far away.

How does Lagarde justify this policy stance? At a general level, she keeps emphasising that the ECB ‘takes a data-dependent approach to determining the appropriate level and duration of restriction’. But this is not very illuminating, as nobody would expect the ECB to take decisions in a ‘data-independent’ manner.

More revealing is her mention of the three elements of the ECB’s ‘reaction function’: the inflation outlook, underlying inflation and the strength of monetary policy.

Inflation outlook

As far as the inflation outlook is concerned, one could argue that with an inflation rate of 2.3 per cent in 2024 and 2.0 per cent in 2025 ‘normalisation’ is warranted. Given the uncertainty bands around the ECB’s inflation forecast, it cannot even be ruled out that ‘headline’ inflation will be below 2 per cent as early as the third quarter of 2024 (at the 60 per cent and 30 per cent lower bounds). But the president is not yet satisfied:

I wish everything was closer to our target. We’re not there yet. We are not there. Even on headline inflation, we are still projecting 2.3 per cent, which is a revision from what we had before. But we’re still at 2.3 per cent in 2024 and we’re at 2 per cent in 2025.

The insistence on hitting the target to a decimal point is hard to reconcile with the ECB’s strategy, which emphasises: ‘The Governing Council confirms the medium-term orientation of its monetary policy strategy. This allows for inevitable short-term deviations of inflation from the target, as well as lags and uncertainty in the transmission of monetary policy to the economy and to inflation.’

Indeed, the strategy sees virtue in this flexibility of the medium-term orientation, which ‘allows the Governing Council in its monetary policy decisions to cater for other considerations relevant to the pursuit of price stability’. It could, for instance, allow consideration of the negative side-effects of the bank’s interest policy on economic growth, the price of overly ambitious disinflation.

Underlying inflation

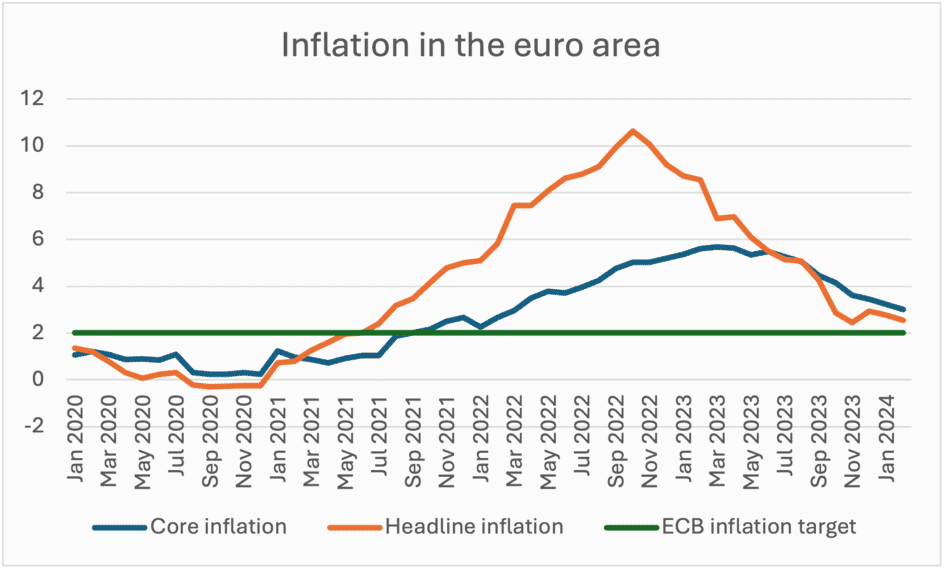

The main indicator of underlying inflation is ‘core’ inflation, excluding energy and food prices. Although it is still at 3.0 per cent, experience shows that this indicator lags behind headline (technically, HICP) inflation and is therefore not a good guide from a forward-looking perspective (see chart). The focus on core inflation may explain why the ECB waited until July 2022 to raise rates, although headline inflation had already reached high levels in autumn 2021.

As regards underlying inflation, the ECB pays a lot of attention to wage developments in the euro area. Indicators of negotiated wages and compensation of employees suggest that a turning point has been reached. In addition, inflation expectations are of particular importance for future wage developments.

The median expectation for inflation three years ahead is 2.5 per cent, which is not significantly different from the ECB’s inflation target.

Monetary policy

While it is highly likely that the ECB will lower its key rates in June, the big question is how quickly and how far. To answer it requires an assessment of a neutral interest rate for the euro area. The concept of the neutral rate goes back to Knut Wicksell (1851-1926), who described it thus:

There is a certain rate of interest on loans which is neutral in respect to commodity prices, and tends neither to raise nor to lower them. This is necessarily the same as the rate of interest which would be determined by supply and demand if no use were made of money and all lending were effected in the form of real capital goods. It comes to much the same thing to describe it as the current value of the natural rate of interest on capital.

There is much debate about the theoretical concepts for measuring the natural rate and the results of empirical studies. A recent study by the ECB concludes that ‘estimates obtained from term structure models and semi-structural models … have ranged between about minus three-quarters of a percentage point to around half a percentage point’. To a large extent, therefore, it could be argued that the neutral or natural real interest rate for the euro is close to zero. With inflation at the 2 per cent target, the neutral nominal interest rate would then also be 2 per cent.

Thus ‘normalisation’ would require a reduction in the ECB’s policy rate to 2 per cent. Given the state of the eurozone economy, it would be advisable to achieve this process in a symmetrical manner, rather than in the gradual, ‘three-season’ approach envisaged by Lagarde. It took the ECB less than a year to raise its policy rate from 2.0 per cent (December 2022) to 4.0 per cent (September 2023). Why should it not be possible to reduce it with the same speed?

The euro area is facing a challenging transformation process due to climate change, digital innovation and competitors such as China and US not bound by fiscal rules. ‘Normal’ interest rates are an important precondition for financing the massive investments needed to achieve this transformation.

This is a joint publication by Social Europe and IPS-Journal