I’m so confident

Yeah, I’m unstoppable today

Song by Sia

In retrospect, it is rather obvious that in 2022 the European Central Bank reacted too late to the inflationary wave that had been building up, mainly due to the Ukraine war. Today, there is again the risk that the ECB is behind the curve. But this time it risks pressing for too long on the brake, with serious risks for the real economy and the stability of the financial system of the euro area.

At her press conference last Thursday, the ECB president, Christine Lagarde, correctly described the current situation as ‘unprecedented’ and ‘exceptional’. The decisions the bank had made since last September, she said, were ‘monumental, by all accounts, both in terms of speed, [and] in terms of height, [the] volume of hikes’. Seven increases from that month, with the latest taking effect this week, have raised the ECB’s key rates by 3.5 percentage points.

After such an historically heavy dose of monetary restriction, one would except the ECB carefully to discuss whether further interest-rate rises remained warranted—or whether it would be better to wait until the effects of its shock therapy had become more visible. Yet, asked to consider skipping envisaged rate rises, Lagarde bluntly replied: ‘In terms of having to pause or having to skip: as I said, number one, we have not discussed it at all and we have not begun thinking about it because we have work to do.’ She left open what kind of work it was that prevented the ECB from its core task of thinking about its policy rates.

Brushed aside

The president dealt in similarly brusque fashion with the quite valid question about the ECB’s estimation of a ‘neutral rate’. A widely discussed theoretical concept, this helps identify whether the current policy rate is restrictive (above neutral) or stimulative (below). Lagarde brushed aside the question without further ado: ‘So, in a way we don’t have to ask ourselves whether we are at neutral rate or not.’

In the absence of such a yardstick, according to what data is the ECB so fully convinced of the necessity for further rate increases? Lagarde elaborated that members of its governing council had looked very much at the data and the ECB had revised its projection of future inflation. Now forecast at 2.2 per cent in 2025, she described this as ‘not satisfactory’ and ‘not timely’.

But while it is useful to base monetary policy decisions on inflation forecasts, the ECB’s performance has been very poor in this regard (see table). For the year 2022, the difference between the figure forecast as of March 2021 and the final outcome was 7.2 percentage points. For the year 2023, so far, the difference between the first estimate and the most recent is still four percentage points. With all due respect to such forecasts, they cannot be regarded as sound evidence for stubbornly raising interest rates.

| Forecast for | |||||

| Forecast date | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | |

| Mar-21 | 1.2 | 1.4 | |||

| Jun-21 | 1.5 | 1.4 | |||

| Sep-21 | 1.7 | 1.5 | |||

| Dec-21 | 3.2 | 1.8 | 1.8 | ||

| Mar-22 | 5.1 | 2.1 | 1.9 | ||

| Jun-22 | 6.8 | 3.5 | 2.1 | ||

| Sep-22 | 8.1 | 5.5 | 2.3 | ||

| Dec-22 | 8.4 | 6.3 | 3.4 | 2.3 | |

| Mar-23 | 8.4 | 5.3 | 2.9 | 2.1 | |

| Jun-23 | 8.4 | 5.4 | 3 | 2.2 | |

| Deviation from first forecast (pp) | 7.2 | 4 | 1.2 | 0.1 | |

A nuanced approach by the ECB to interest-rate policy would start with the widely-shared insight that monetary policy is operating with long and variable lags. Lagarde concurred, to a degree: ‘There is some lag time—not that much by textbook standards, which will typically say that it’s anywhere between 18 and 24 months, maybe a bit more.’

A direct implication of such lags is that the effect of today’s—indeed yesterday’s—policy measures on inflation will only materialise after some time. If the central bank continues hiking rates until it clearly sees inflation come back to target, it will thus be too late in abandoning a restrictive stance. Asked about such transmission lags, Lagarde however said: ‘Suffice to say that we are seeing it already. Do we see all of it? Obviously, no. We want to see it all the way down to inflation.’

Short-term dynamics

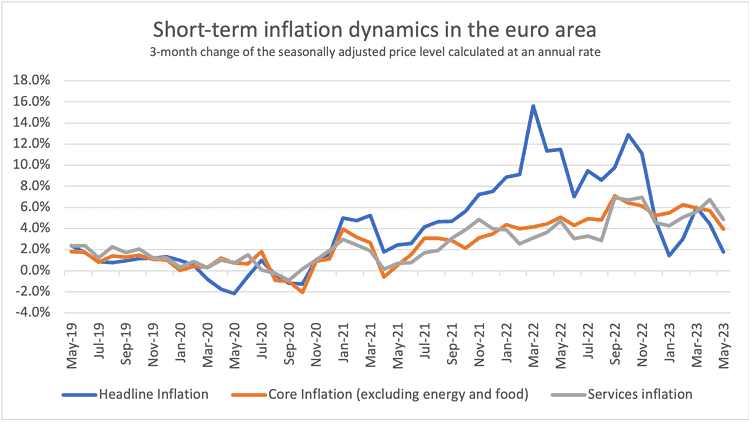

Given all the uncertainties about the inflation outlook, it is surprising that the ECB’s policy statement only mentions the year-on-year inflation rates—so, for instance, the rate in May 2023 was the difference in the price level with May 2022—but not the short-term dynamics. Due to the strong inflation shock in 2022, with this approach there is a delay before a more recent deceleration of inflation becomes obvious.

Short-term inflation dynamics can be made visible by calculating the change in the (seasonally-adjusted) price level over, say, three months. To make this comparable with the annual data based on the year-on-year calculation, the three-month change is raised to the power of four.

Adopting this practice, widely used in the United States, one can see that inflation in the euro area has already decelerated significantly (see chart). In May 2023, the headline rate was only 1.8 per cent. Core inflation (excluding food and energy) has come down to 3.9 per cent and even inflation in services, which the ECB regards with particular concern, shows some slowing.

Of course, such short-term dynamics can be volatile and misleading. But it is unclear why, in its public communication, the ECB is not making use of such information. From the public’s side, fortunately the bank’s survey of consumer inflation expectations shows eurozone households anticipate an inflation rate of 2.5 per cent for the next three years—so low expectations are relatively well anchored.

Coarse rhetoric

What could be the motivation behind the ECB’s coarse rhetoric (‘we have work to do’)? Does the bank want to manifest hawkishness after having been too dovish in 2022? Is it trying to impress the German audience which for years complained about the ECB’s purported lack of orientation towards price stability?

In the current situation, monetary policy faces not only a difficult trade-off between price stability and growth but also a balancing act between price and financial stability. While there is no doubt price stability is the ECB’s main target, its president should at least explain more convincingly why an ever-increasing dose of interest-rate hikes is really warranted.

This is a joint publication by Social Europe and IPS-Journal

Peter Bofinger is professor of economics at Würzburg University and a former member of the German Council of Economic Experts.