The recent Economic Outlook interim report from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development makes puzzling reading.

On the one hand, the OECD openly expresses serious doubts about the recovery it forecast in the spring outlook, warning that the ‘pick-up in growth in the first half of 2023 may prove short-lived’ and ‘recent signals point to a loss of momentum’. The impact of past monetary tightening could prove ‘stronger than anticipated’ because of the ‘rapid and simultaneous tightening around the world’, historically high debt loads and the risk of triggering ‘stress in the financial system’. And ‘even if interest rates are not raised further, the effects of past rises will continue to work their way through the economy for some time’.

All this confirms concerns trade unions expressed a year ago on the economic impact of the greatest monetary tightening in the last four decades.

On the other hand, the OECD is not moving an inch on policy. Despite recognising that the full effect of cumulative tightening over the past year is still to hit economies, it calls for monetary policy to remain restrictive, with scope for any policy-rate reduction likely to remain limited ‘well into 2024 in most advanced economies’. The organisation also urges governments to join central banks in fighting inflation by re-engaging with fiscal austerity and scaling back fiscal supports.

The OECD is clearly sticking to the narrative that inflation is the result of too much purchasing power chasing too little supply. Cooling demand pressures to depress the economy is then not just a regrettable side-effect of monetary policy but the key mechanism by which the inflation genie is put back in the bottle.

Facts do not match

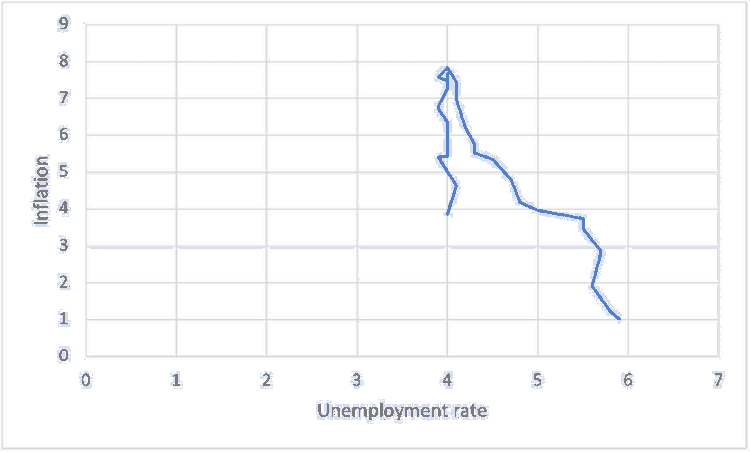

Economic behaviour however contradicts this story. If an overheating economy were driving inflation, monetary restriction would reduce demand, economic activity and employment, pushing unemployment up and inflation down. This is what happened in the 1970s, when large increases in unemployment pulled down record inflation. Yet today inflation is going down withoutunemployment shooting up (Figure 1).

The graph indicates inflation in the G7 halving from mid-2022 while unemployment has stabilised at a low(er) level. Indeed jobs are being added in record numbers: between the first quarter of 2022 and the first or second quarter of 2023, the United States and the euro area added more than three million jobs each, while Canada and Australia expanded their employed populations by 3 and 4.5 per cent respectively. Facts do not match the OECD’s inflation narrative.

Figure 1: G7 inflation and unemployment from January 2021 to July 2023

Inflation is instead driven by the supply side. Pandemic-linked disruptions—bottlenecks in global supply chains, the invasion of Ukraine, production shifting from services based on human interaction to consumer goods and back—are in the process of reversing. Global supply chains are being repaired and workers moving into sectors where labour is in higher demand. Inflation is thus coming down of its own accord, without much need to push unemployment up by squeezing demand.

Research from the Roosevelt Institute in the US confirms this. Examining changes in price and quantity of items of core consumption, it finds that three-quarters of US disinflation between December 2022 and July 2023 was driven by expanding supply, not decreasing demand.

Severe downturn in prospect

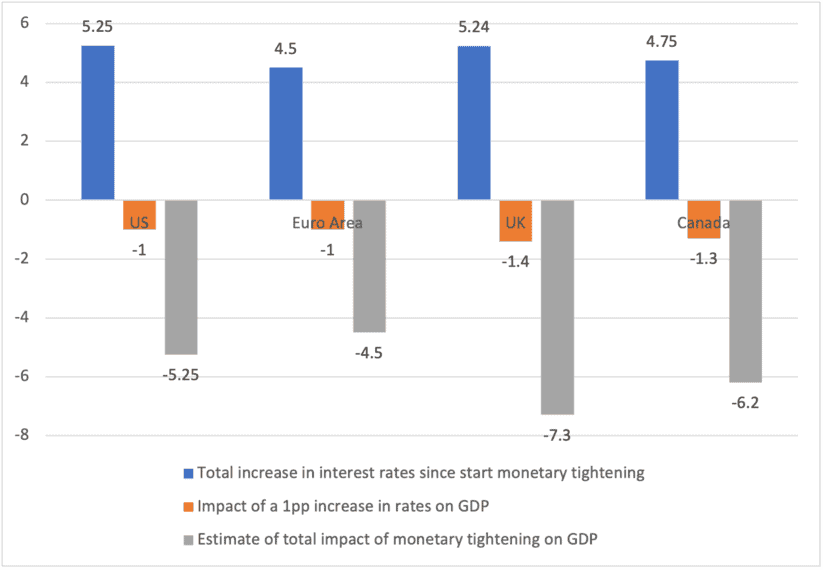

The fact that inflation is much less embedded than presumed by the narrative of an overheating economy matters enormously: it means central banks are over-tightening monetary policy. Interest-rate hikes are forecast to pull economic activity down by five to seven percentage points (Figure 2). This will destroy most, if not all, of the post-pandemic recovery by bringing economic activity back to its 2019 level. As the excess-demand narrative is wrong and inflation is mainly linked to temporary supply disruptions now reversing, these sacrifices of economic activity and jobs will be largely unnecessary.

Figure 2: full impact of interest-rate hikes on gross domestic product

To make things worse, the timing is wrong. As stressed by the OECD’s interim report, monetary policy works with substantial time lags and much of the impact of this tightening still lies ahead. The chances are that it will hit economies and labour markets fully when inflation is approaching price-stability targets. By boosting disinflation at the wrong time, central banks will thrust the economy back into the ‘lowflation’ of the previous decade, when inflation remained too close to zero to be comfortable and central banks were unable to lift the economy out of this trap.

Finally, this misguided policy hits workers with a double whammy. After suffering substantial real-wage losses in the cost-of-living crisis, they face the prospect of a severe economic downturn destroying jobs. Adding insult to injury, the downturn will force workers to accept renewed wage ‘moderation’. This will further increase profit shares, already high after businesses used the cost-of-living crisis as an excuse to increase prices more than could be justified by higher costs.

Trying to fix supply-side problems by doubling down on the demand side is a bad idea. The OECD and central bankers—including the European Central Bank—should know better.

Ronald Janssen is senior economic adviser to the Trade Union Advisory Committee of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. He was formerly chief economist at the European Trade Union Confederation.