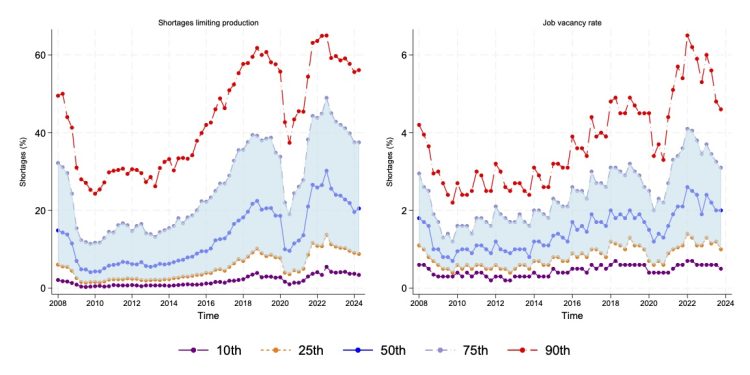

Labour shortages have become one of the most pressing issues in the labour market across Europe, coming to the forefront since the pandemic. While they are somewhat declining from their peak in 2022, there are still widespread shortages throughout the European Union. Crucially, shortages have risen across a diverse range of countries and sectors (see figure 1) and are quite pervasive throughout the economy. The common trends mask substantial variation, with some jobs experiencing genuine skill shortages, particularly in specific roles and sectors such as ICT or very specialised profiles in the construction sector. Meanwhile, many other sectors are struggling to compete for the available workers in the labour market and face a labour shortage in a stricter sense.

These shortages reflect both structural factors, such as an ageing population and the demand for labour from the green and digital transitions, as well as cyclical trends. As with the drivers, the solutions are varied too. While much of the debate focuses on skills shortages, which feature heavily in the commission action plan, or on attracting new migrants to fill shortages, one aspect receives less attention: with more opportunities, workers are choosing the more attractive positions. It is also no coincidence that it is precisely those jobs that are less attractive that have experienced the highest rise in shortages since the pandemic. This remains the case among similar countries and sectors, where there is a negative association between wages and shortages, meaning shortages are relatively higher where wages are relatively lower. However, as employers compete for workers, this offers opportunities by raising workers’ prospects and providing them with greater bargaining power.

Attracting workers in times of shortages

Indeed, when asking employers about their strategies for dealing with shortages, one of the key methods is to increase the benefits of the job, along with measures such as allowing for more telework or remote work and fostering a better work-life balance. This may particularly benefit those workers who have been left behind and have seen limited wage growth under the pressures of technological change and globalisation, as well as a weakening of the collective bargaining that can provide them with support. Over time, there indeed seems to have been a marked move in bargaining power away from workers, as can also be seen in the downward trajectory of the labour share of income. Labour shortages may help redress this balance.

Even in the United States, where inequality has been seemingly unstoppable, with lower-paid workers being left behind, wage inequality has reversed recently as labour shortages and demand for workers have increased wages, particularly at the bottom.

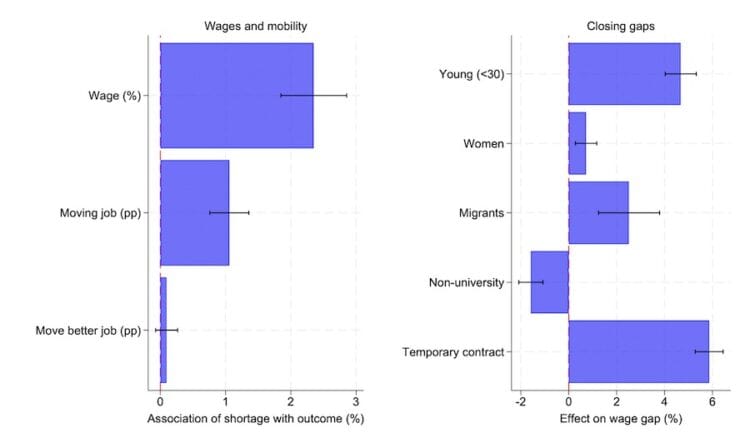

A direct link between shortages and workers’ outcomes

Indeed, in a new ETUI working paper, I show that, across the EU, workers in jobs where employers report experiencing higher shortages by one percentage point have a 2.5 per cent higher wage than otherwise similar workers. Partly, this is because they are more likely to have only recently moved to this new job, as more workers are transitioning towards jobs with more significant shortages, likely because they are enticed. Using data on workers across the EU, I show in a new working paper that being in a job facing x per cent higher shortages is associated with wages that are 2 per cent higher than those of otherwise similar workers (figure 2- left) as well as with a greater probability of having only recently moved to that job, presumably in search of better conditions. Indeed, recent movers have benefited even more from a higher wage resulting from labour shortages. Crucially, too (figure 2-right), the positive wage effect is particularly pronounced for more vulnerable workers – the young, women, migrant workers, and those on temporary contracts. The key exception is the lower educated, who are still losing out.

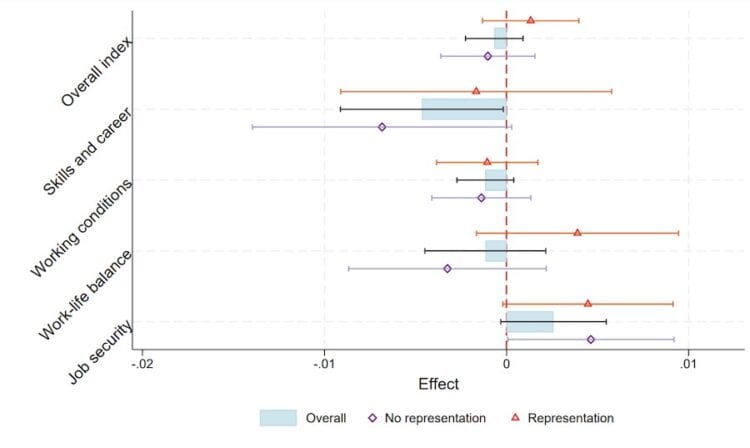

Worker representation remains important

The picture is more varied when examining broader job quality (figure 3), where it is evident that workers themselves are also negatively affected by labour shortages, which can lead to adverse working conditions. Indeed, higher labour shortages are associated with somewhat worse working conditions on average and fewer prospects for training and career progression in particular, while also being linked to greater job security as employers seek to retain their workers. Crucially, workers who have access to worker representatives are shielded from these more negative associations.

Conclusion

In conclusion, I argue that working conditions and job quality are crucial in addressing labour shortages. A significant part of the issue lies in attracting workers, who now have greater options and choices. This can be particularly beneficial for those at the lower end of the pay distribution, who have been finding their bargaining positions increasingly weakened. That said, there is also room for attracting workers with specific skills and providing more training to fill skills gaps that are prevalent in some, but not all, of the shortage occupations.

Wouter Zwysen is a senior researcher at the European Trade Union Institute, working on labour-market inequality and wages, and ethnic and migrant disadvantage.