Despite its name, the key objective of the European Union directive on adequate minimum wages adopted in October 2022 is not only to ensure adequate minimum wages. It is also about promoting collective bargaining on wage-setting. Although EU member states still have until mid-November this year to transpose the directive into national law, it is already influencing developments on both fronts in a range of countries.

The directive lists four criteria to be taken into account by member states when setting statutory minimum wages. But it also offers indicative reference values: 60 per cent of the gross median wage (which half of wage-earners fall below) and 50 per cent of the gross average wage. These effectively establish a ‘double decency threshold’ for a national minimum wage—not legally binding but a strong normative benchmark even ahead of formal transposition of the directive.

Countries with higher wage levels will tend to use 60 per cent of the median as the benchmark, countries with lower levels 50 per cent of the average. Many central- and eastern-European countries, in particular, have rather low median wages, so the median is not a suitable indicator.

Influencing wage-setting

The double decency threshold can influence national minimum-wage setting in four main ways. The most direct is through integration into national law. In Bulgaria, the Labour Code was amended in February 2023 to stipulate that the statutory minimum wage would be set at 50 per cent of the average gross wage on September 1st each year. Czechia amended its Labour Code in March this year, stipulating that the statutory minimum wage should reach at least 47 per cent of the average wage by 2029. Other countries had already introduced reference values before the directive was adopted: in Lithuania, for instance, the minimum wage should be between 45 and 50 per cent of the average. In Slovakia the law goes even further than the double decency threshold, stipulating that the minimum wage should be 57 per cent of the average.

The second route is via the threshold guiding political decision-makers. In Croatia, a government decree setting the statutory minimum wage for 2024 made explicit reference to it. In Malta, the Low Wage Commission did likewise in its recommendation. In Ireland and Estonia the threshold is used as a reference for plans to increase the minimum wage over time. In Ireland, the government made a commitment to increase the statutory minimum wage to 60 per cent of the national median wage by 2026. In Estonia, trade unions, employers and the government concluded a tripartite ‘goodwill agreement’ in May 2023 aiming to increase the statutory minimum wage to 50 per cent of the average by 2027.

Thirdly, in some countries the threshold has prompted a debate on the adequacy of minimum wages and whether it should be the official reference point. In Germany, for instance, the extraordinary increase in the minimum wage in October 2022—justified by reference to the then draft directive—enhanced the political debate about inserting the reference value of 60 per cent of the gross median wage into the minimum-wage law. Discussions about the appropriate indicator for the adequacy of minimum wages are also under way in Latvia and Spain.

Fourthly, the double decency threshold is already influencing minimum-wage policies by providing trade unions with an additional argument. In Hungary and Romania, trade unions used the threshold in pursuit of a higher minimum-wage increase in discussions with the government and employers. In the Netherlands, the Dutch Federation of Trade Unions (FNV) is campaigning for a fair minimum wage of €16 per hour. FNV’s slogan, Voor een better bestaan—60% Mediaan (For a better life—60 per cent of the median), explicitly refers to the median version of the threshold. Indeed, the directive has already even influenced trade-union demands beyond Europe: the Japanese Trade Union Confederation, Rengo, has called for a gradual increase of the minimum wage from 46 per cent to 60 per cent of the median, referring to the directive.

Increasing bargaining coverage

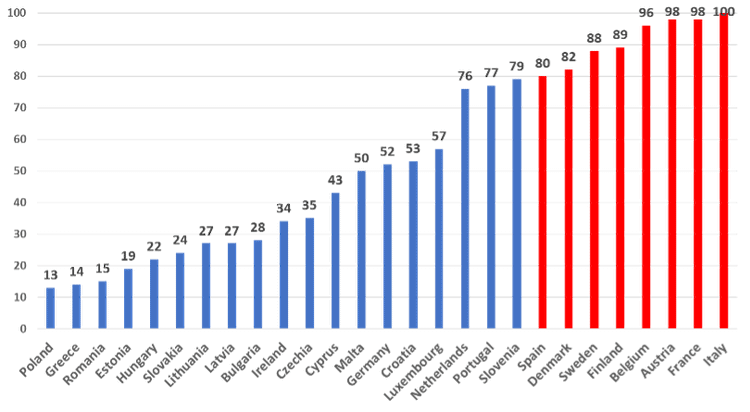

To promote (sectoral) collective bargaining, the directive obliges member states with less than 80 per cent bargaining coverage to establish an action plan to promote collective bargaining and to increase coverage progressively. As the chart below indicates, only eight member states meet this coverage threshold, so most will be required to produce such an action plan.

Collective-bargaining coverage (%) in the EU (2021 or most recent year available)

As with the double decency threshold for adequate minimum wages, this benchmark for adequate bargaining coverage is already influencing reform debates in a range of countries in advance of transposition. In Ireland, where coverage is 34 per cent, a tripartite High-level Working Group was set up in March 2021 to make recommendations to increase bargaining coverage to 80 per cent. In Germany, this threshold has also become a point of reference in the debates on how to reverse the decline in coverage. The Ministry of Labour has announced a legal package to promote collective bargaining, which among other things will include a draft federal public-procurement law. Such a Bundestariftreuegesetz would aim to ensure that public contracts at national level were only awarded to companies applying the provisions of collective agreements.

The obligation to promote collective bargaining will likely have the most far-reaching consequences in central and eastern Europe where collective agreements, with the exception of Croatia and Slovenia, cover only one third of the workforce—or even less. In Romania, a new law on social dialogue was passed in December 2022. Aiming to strengthen collective bargaining at all levels (and promote unionisation), this essentially reverses most of the measures introduced in 2011 to decentralise and weaken it. For most central- and eastern-European countries, however, a significant increase in collective-bargaining coverage would require a regime change from a primarily company-based to a more sector-based bargaining system.

Concrete significance

Even before its formal transposition into national law, the directive has influenced minimum-wage setting and collective bargaining in various countries. The double decency threshold contributed significantly to the substantial minimum-wage increases applying this year.

But the concrete significance of the directive will ultimately be determined by its implementation at national level. Since it does not define binding standards but rather creates a political frame of reference, strengthening those domestic players who advocate adequate minimum wages and strong collective bargaining, enforcement will be contested. We are not done yet with the enactment of the directive.