Europe’s economies weathered the pandemic relatively well but new crises have quickly followed. Covid-19 exacerbated some structural shortages on the labour market via a surge in demand for goods and services. Companies are clamouring for workers and struggling to fill vacancies. These labour shortages bring with them production problems, and add stress to short-staffed businesses.

Discussions often centre on a skills mismatch and a shortage of skilled workers, leading to a call for more skilled migrants. This does not however completely fit what we see in European labour markets.

Low unemployment

First of all, there is a very wide range of shortage occupations, with some high-skill (such as software developers) but also some less-skilled (such as waiters). The requirement of university qualifications is actually lower among shortage occupations than across the labour market overall—pointing to the importance of on-the-job training.

Secondly, these labour shortages coincide with low unemployment rates, around 7 per cent overall in the EU. So there is not a reserve of workers looking for work but lacking the necessary skills to fill the vacancies, which is what we would expect in a skills shortage.

Thirdly, while mobility might help with some of the shortages, most are occurring in many countries simultaneously, as shown in a recent excellent report by the European Labour Authority. Migrant labour may also not legitimately be used to reduce working conditions or wages.

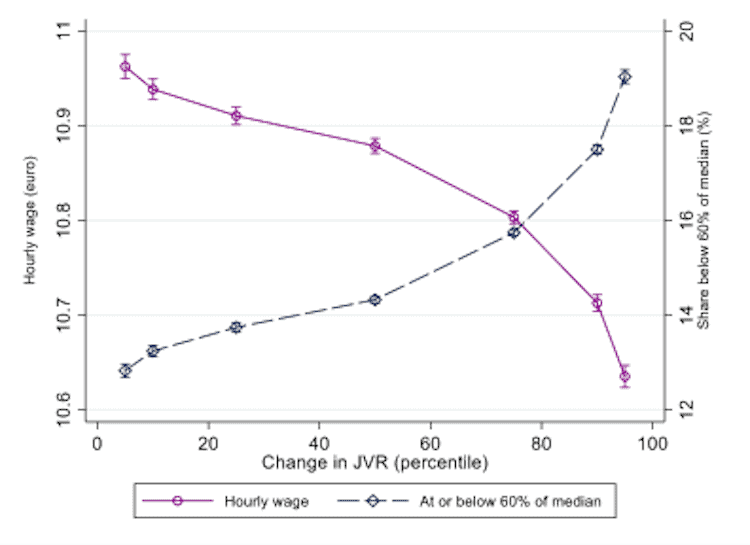

The sectors where vacancy rates have risen most within EU member states (data lacking for France) are characterised by a higher-than-average share of workers on insecure contracts, working under high pressure and to tight deadlines and more often unsocial hours. In sectors where there has been a bigger increase in vacancies (towards the right end of the horizontal axis in Figure 1), the average real wage (purple line) is relatively low and the share of workers below the poverty-wage threshold (grey dashes) relatively high.

Importantly, this takes account of how workers and firms differ, controlling for occupation, education, gender, age and company size. It shows very clearly the inverse relationship between pay and the extent to which shortages have increased.

Figure 1: change in job vacancy rate from 2018 to 2022 plotted against hourly wage and share of wage-earners up to 60 per cent of the median (2018) by country and sector

Opportunity for equality

It is clearly harder to fill vacancies in jobs that are just not attractive enough. Indeed, tight labour markets provide scope, sometimes neglected, to strengthen workers’ bargaining power.

Crucially, this mainly benefits workers who are more vulnerable and generally earn less. Relatively full employment gives the more disadvantaged opportunities they do not otherwise enjoy to assert their claims, and in so doing reduce inequalities.

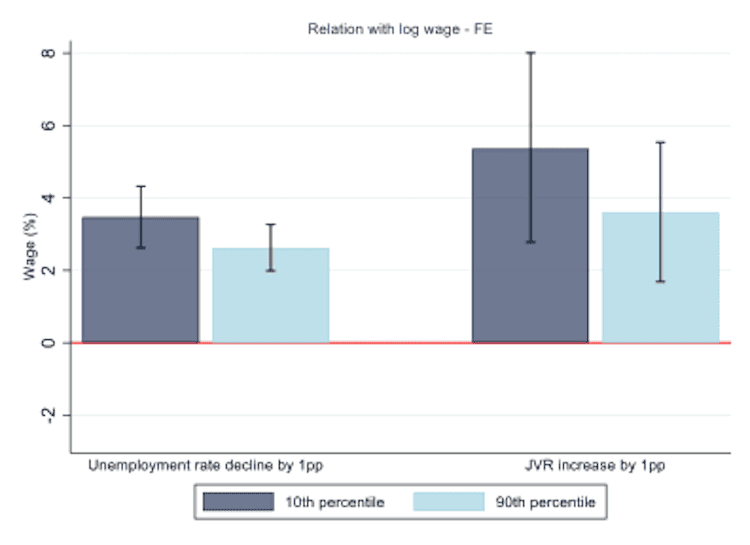

In Europe historically we can see that tighter labour markets—as the unemployment rate drops or the rate of unfilled vacancies increases—are associated with larger wage gains for lower than for higher earners. If job vacancy rates increase by one percentage point, wages at the bottom increase by 3.4 per cent on average, compared with 2.6 per cent at the top of the distribution (Figure 2).

Figure 2: estimated effects of percentage-point declines in unemployment or increases in job vacancies on real wages at the 10th and 90th within-country income percentiles

In this crisis both companies and workers must be supported, but it is important that the opportunity is also taken to improve working lives and not to sustain poor conditions and low pay. It is crucial to ensure that all jobs offer good enough conditions for workers to live dignified lives, which in turn will attract more workers to these occupations.

This means wage increases, but also more secure contracts, less inflexible and difficult working times, and more training and support for workers to grow within their jobs. This European Year of Skills is a good moment to make the case for empowering Europe’s workforce with the right skills and training, while providing good-quality jobs.

Wouter Zwysen is a senior researcher at the European Trade Union Institute, working on labour-market inequality and wages, and ethnic and migrant disadvantage.